Dec. 28th 2009

Today, we bring you an interview (the second part, and complete transcript) with Edward Hugh, a macro economist, who specializes in growth and productivity theory, demographic processes and their impact on macro performance, and the underlying dynamics of migration flows. Edward is based in Barcelona, and is currently engaged in research into the impact of aging, longevity, fertility and migration on economic growth. He is a regular contributor to a number of economics blogs, including India Economy Blog, A Fistful of Euros, Global Economy Matters and Demography Matters.

Forex Blog: I’d like to begin by asking if there is any significance to the title of your blog (“Fistful of Euros”), or rather, is it only intended to be playful?

Obviously the title is a reference to the Segio Leone film, but you could read other connotations into it if you want. I would say the idea was basically playful with a serious intent. Personally I agree with Ben Bernanke that the Euro is a “great experiment”, and you could see the blog, and the debates which surround it as one tiny part of that experiment. As they say in Spanish, the future’s not ours to see, que sera, sera. Certainly that “fistful of euros” has now been put firmly on the table, and as we are about to discuss, the consequences are far from clear.

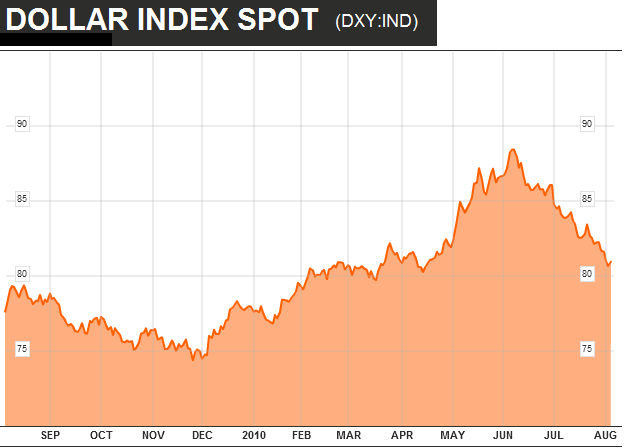

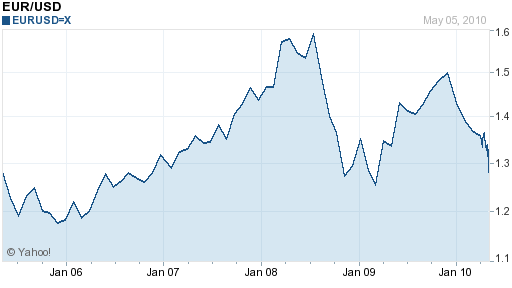

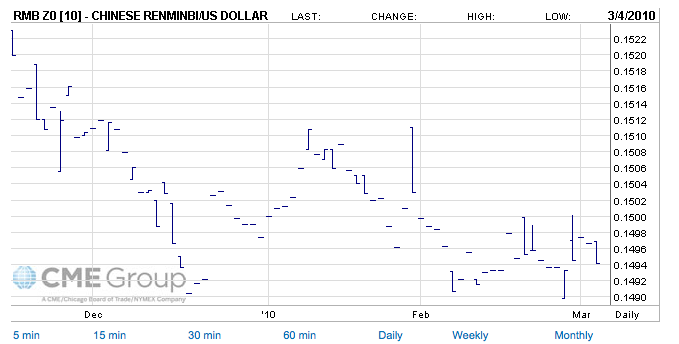

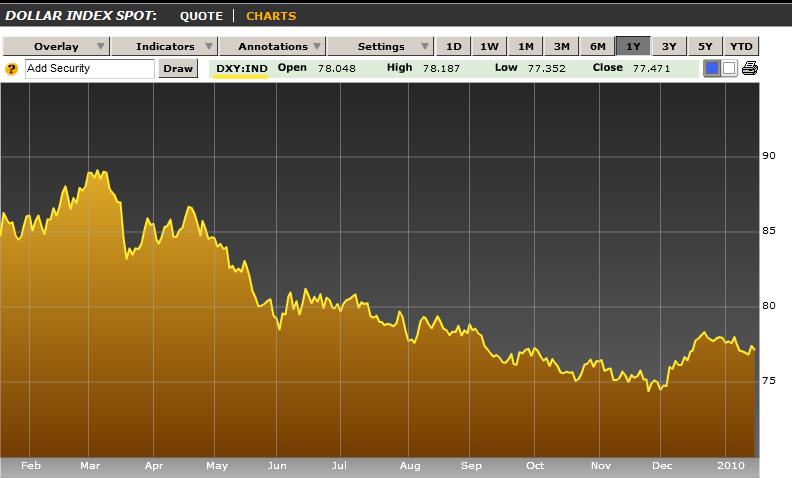

Forex Blog: You wrote a recent post outlining the US Dollar carry trade, and how you believe that the Dollar’s decline is cyclical/temporary rather than structural/permanent. Can you elaborate on this idea? Do you think it’s possible that the fervor with which investors have sold off the Dollar suggests that it could be a little of both?

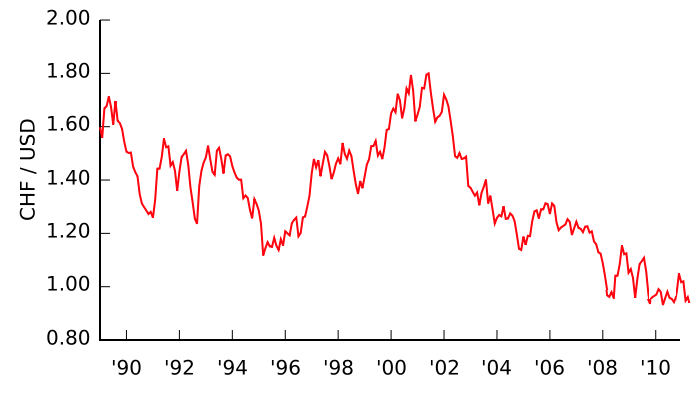

Well, first of all, there is more than one thing happening here, so I would definitely agree from the outset, there are both cyclical and structural elements in play. Structurally, the architecture of Bretton Woods II is creaking round the edges, and in the longer run we are looking at a relative decline in the dollar, but as Keynes reminded us, in the long run we are all dead, while as I noted in the Afoe post, news of the early demise of the dollar is surely vastly overstated.

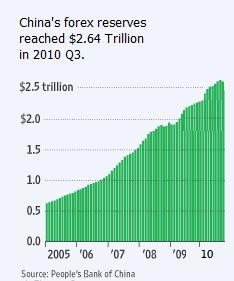

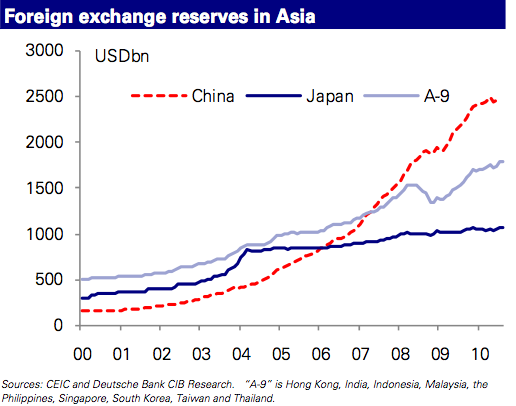

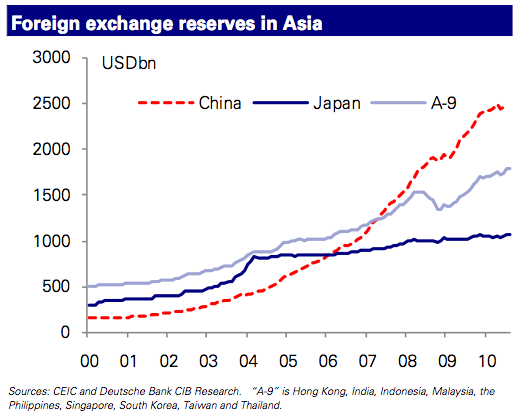

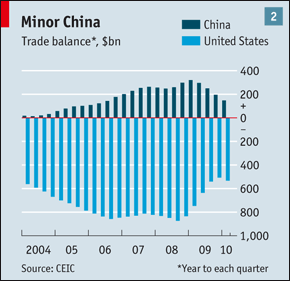

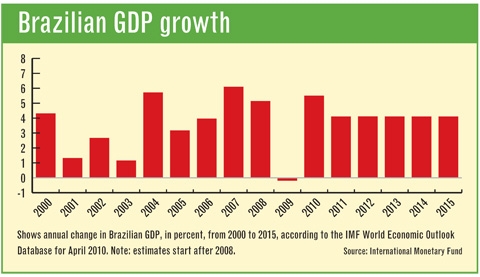

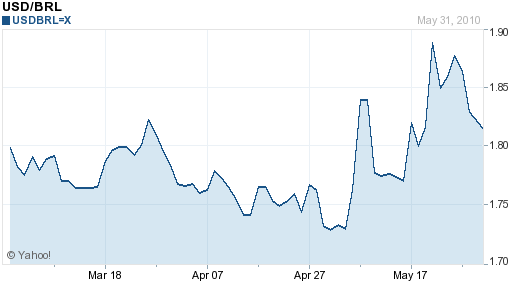

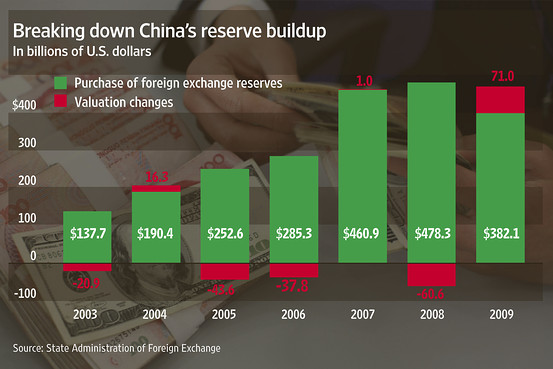

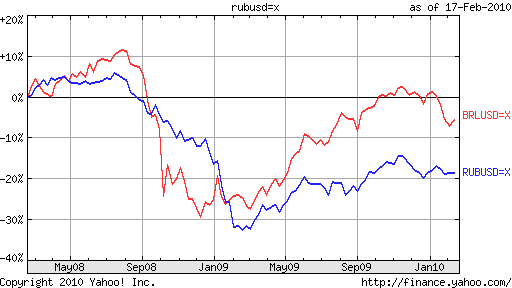

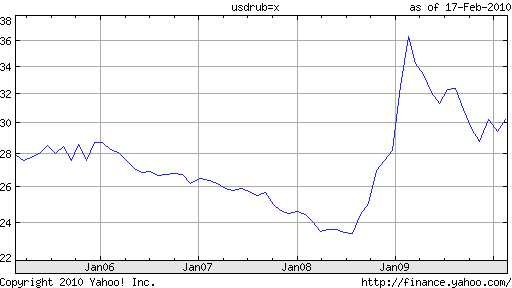

Put another way, while Bretton Woods II has surely seen its best days, till we have some idea what can replace it it is hard to see a major structural adjustment in the dollar. Europe’s economies are not strong enough for the Euro to simply step into the hole left by the dollar, the Chinese, as we know, are reluctant to see the dollar slide too far due to the losses they would take on dollar denominated instruments, while the Russians seem to constantly talk the USD down, while at the same time borrowing in that very same currency – so read this as you will. Personally, I cannot envisage a long term and durable alternative to the current set-up that doesn’t involve the Rupee and the Real, but these currencies are surely not ready for this kind of role at this point.

So we will stagger on.

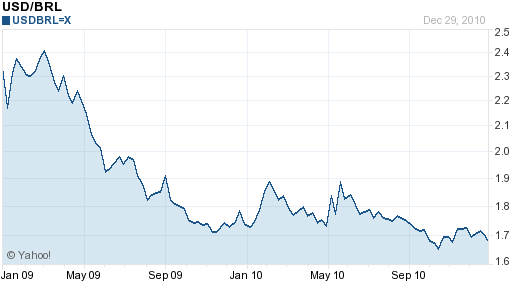

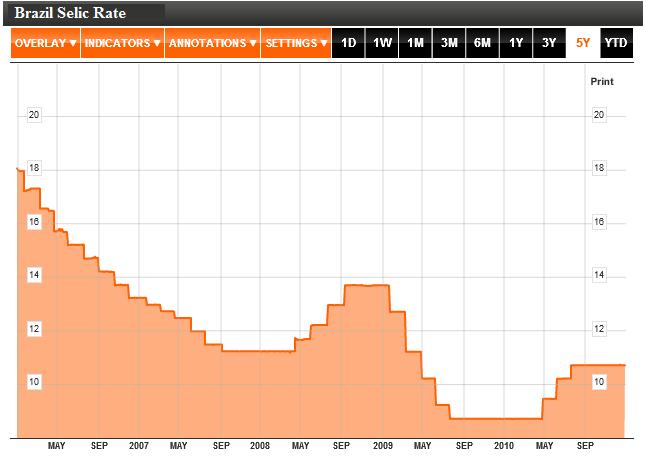

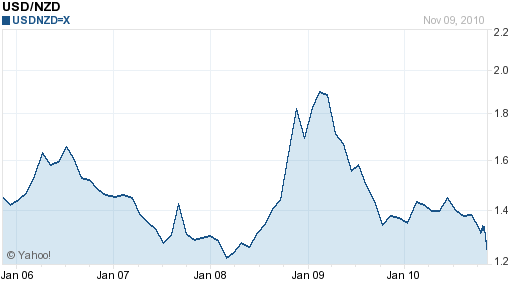

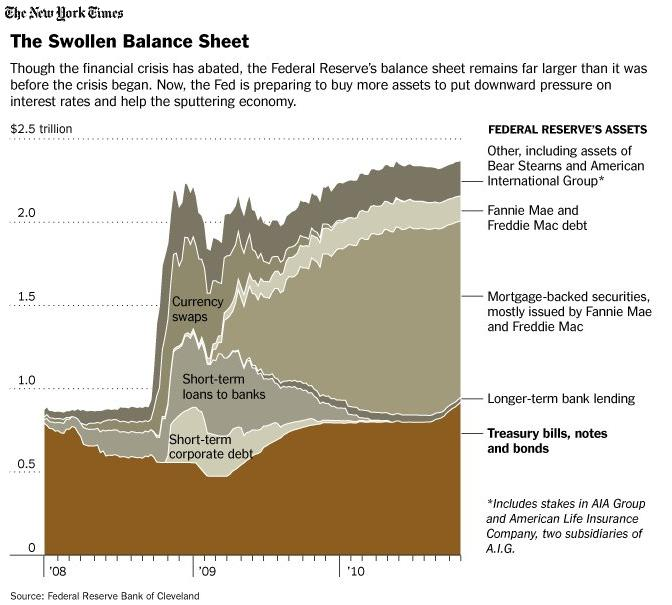

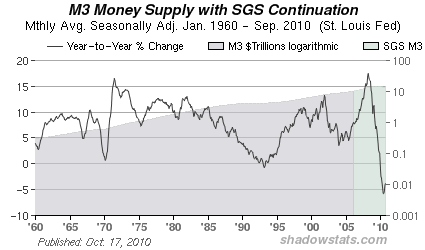

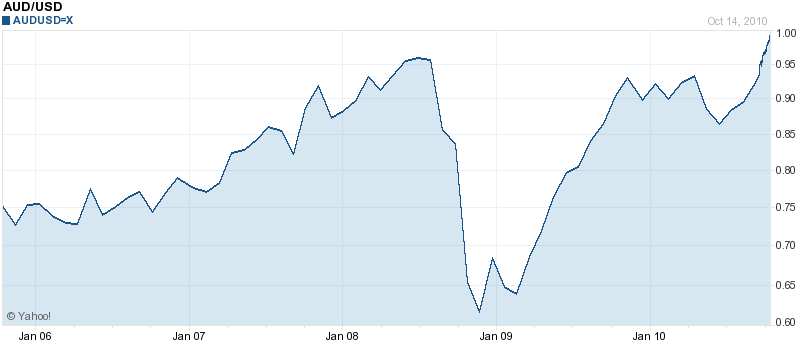

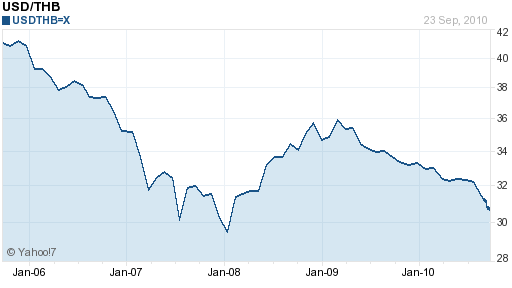

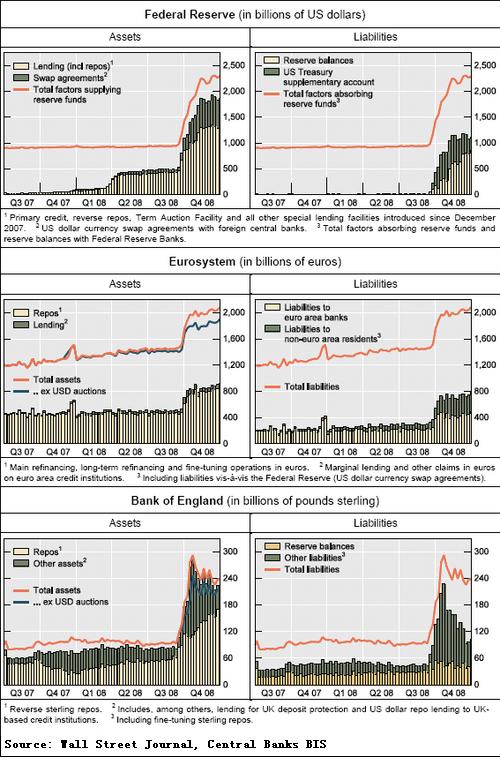

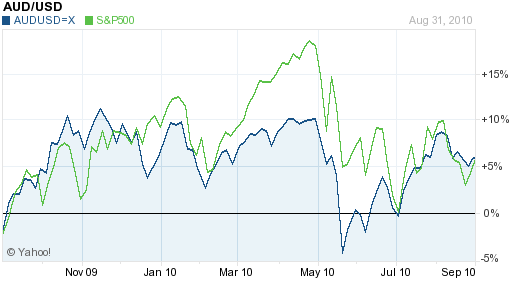

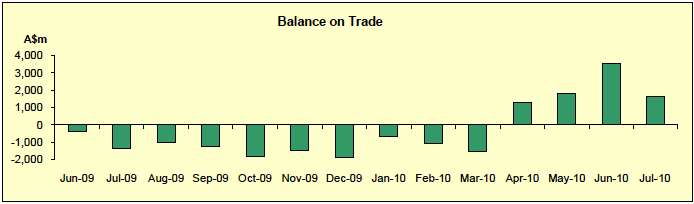

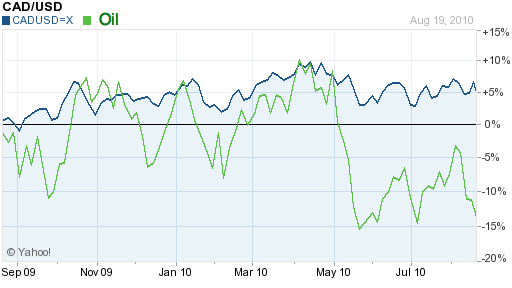

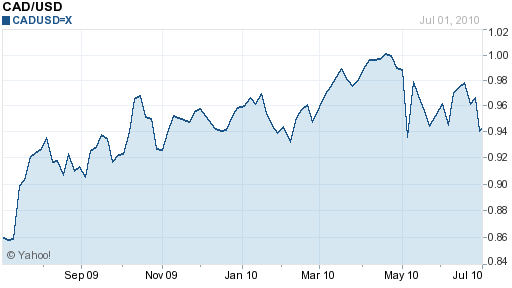

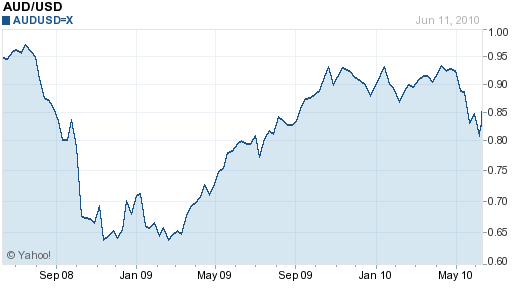

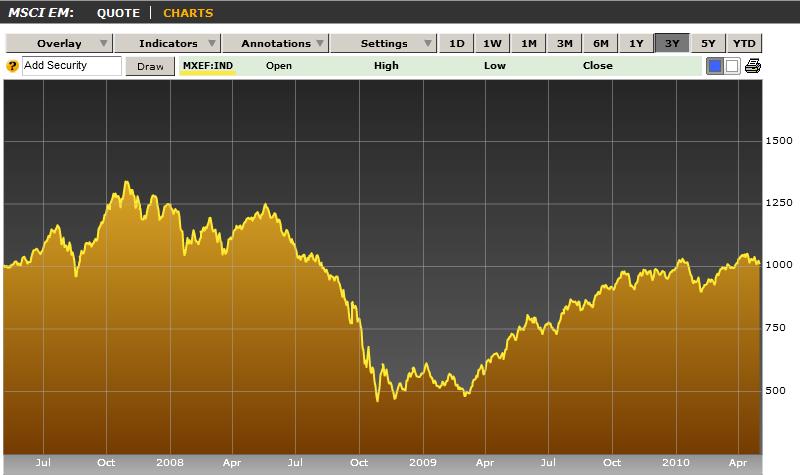

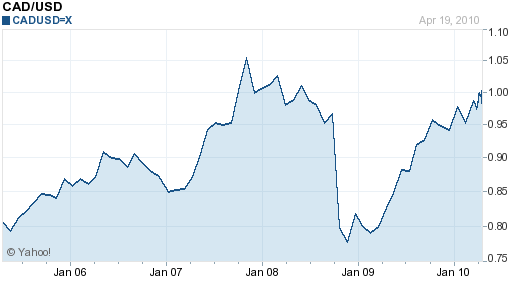

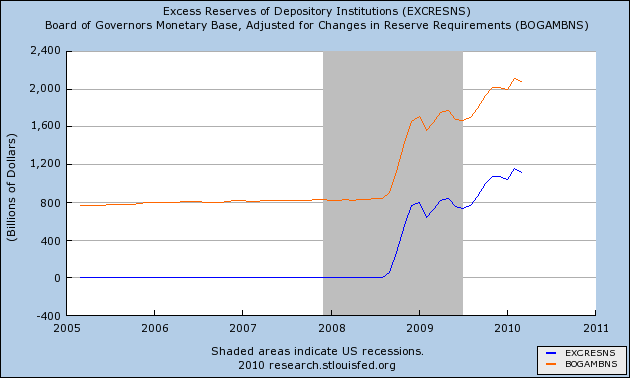

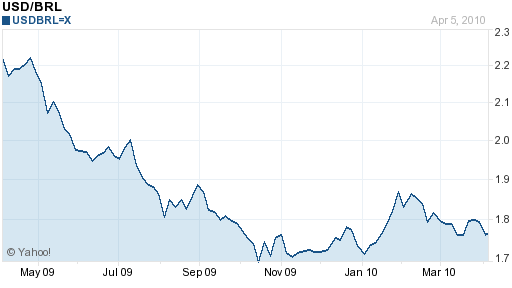

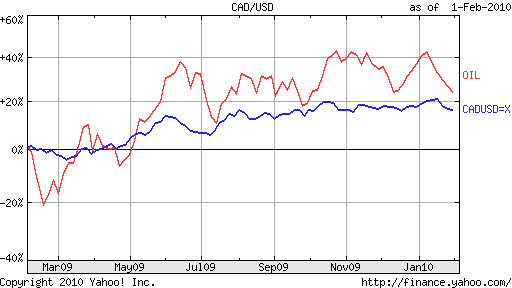

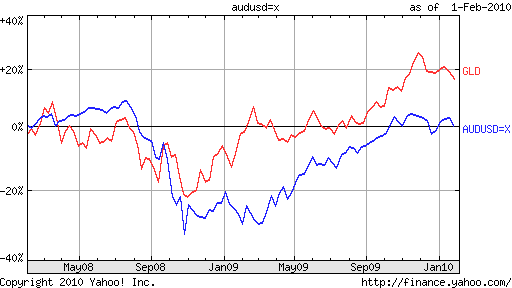

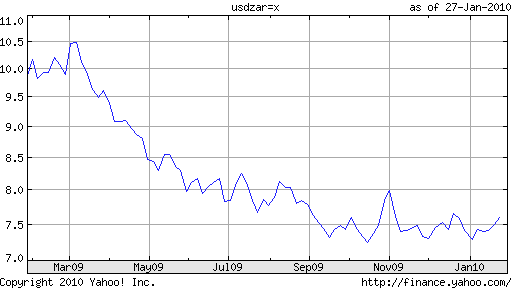

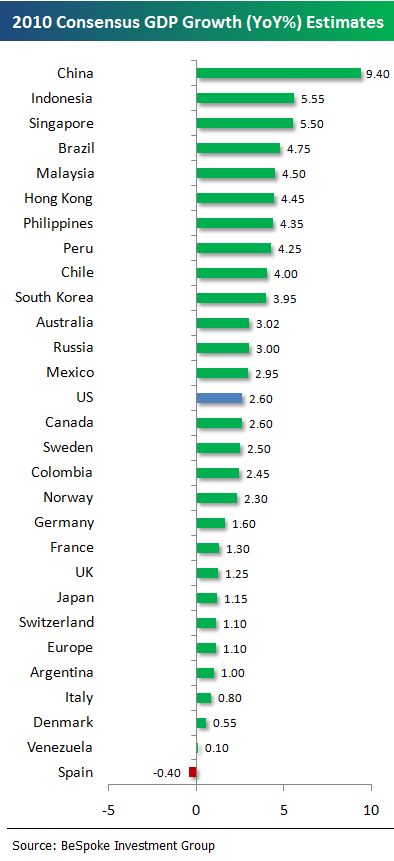

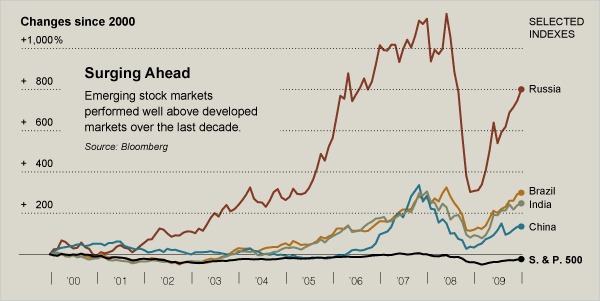

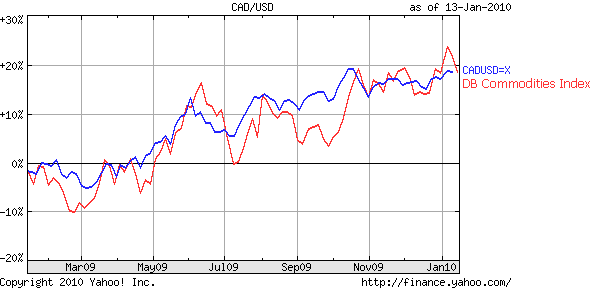

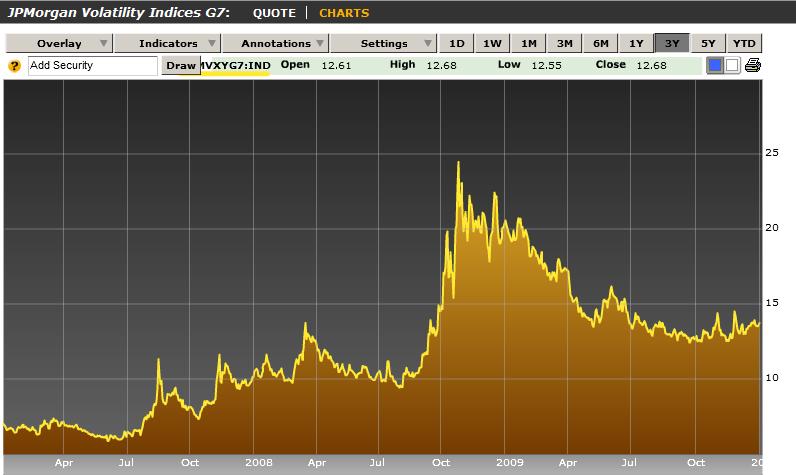

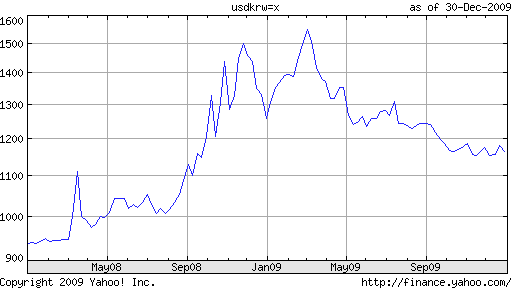

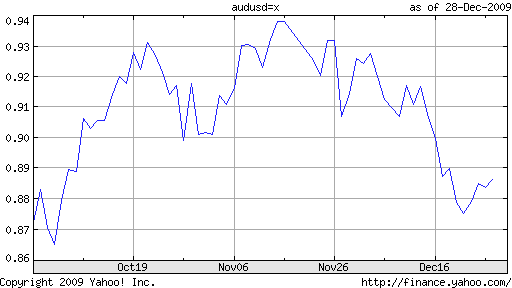

On the cyclical side, what I am arguing is that for the time being the US has stepped in where Japan used to be, as one side of your carry pair of choice, since base money has been pumped up massively while there is little demand from consumers for further indebtedness, so the broader monetary aggregates haven’t risen in tandem, leaving large pools of liquidity which can simply leak out of the back door. That is, it may well be one of the perverse consequences of the Fed monetary easing policy that it finances consumption elsewhere – in Norway, or Australia, or South Africa, or Brazil, or India – but not directly inside the US.

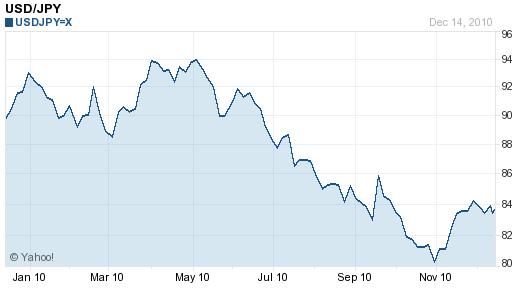

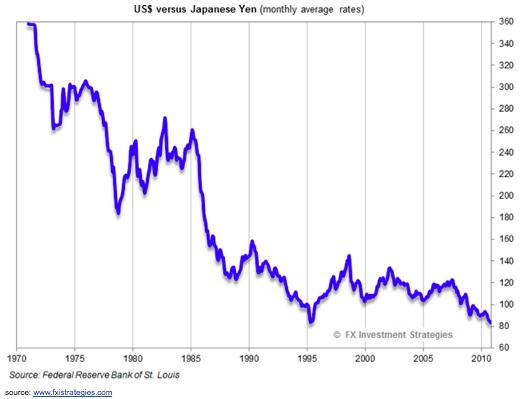

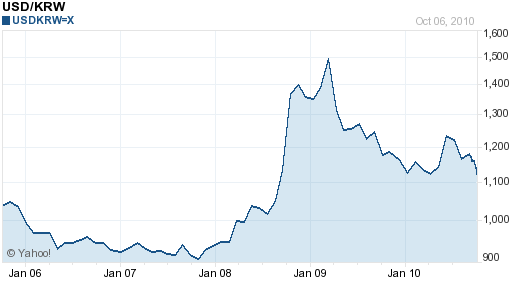

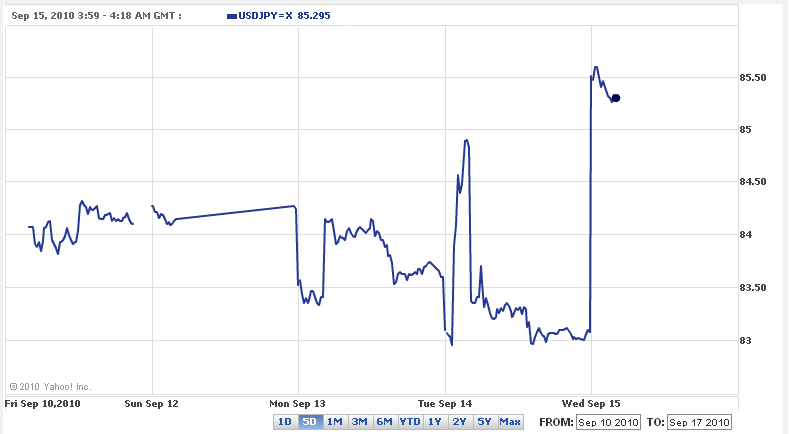

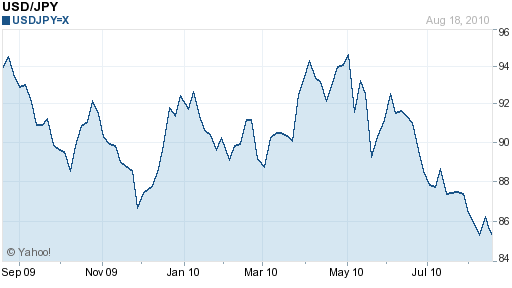

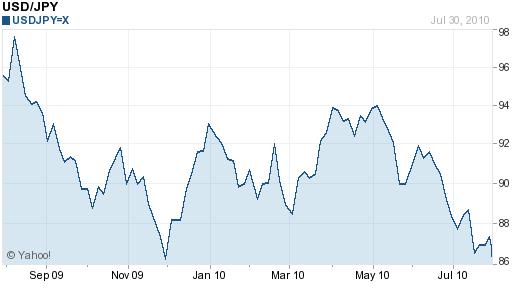

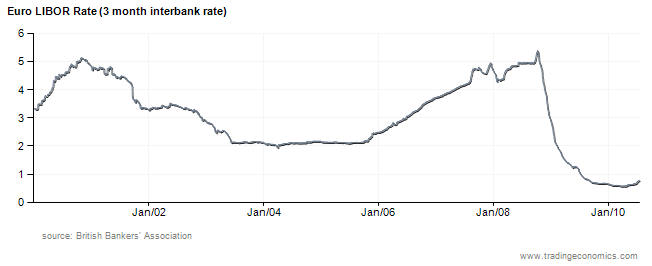

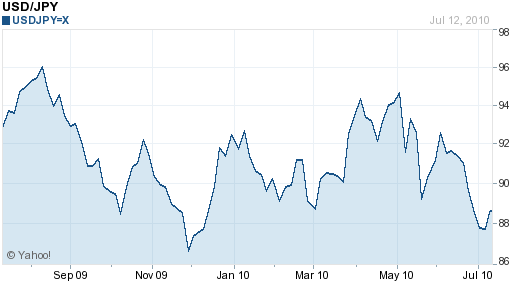

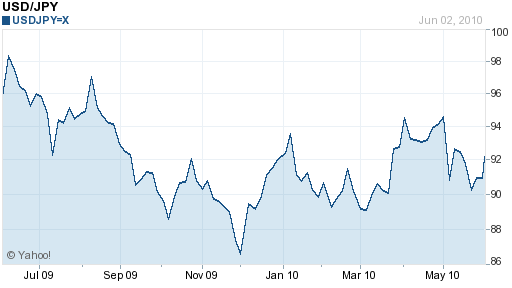

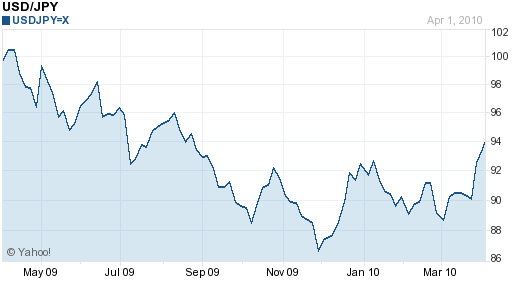

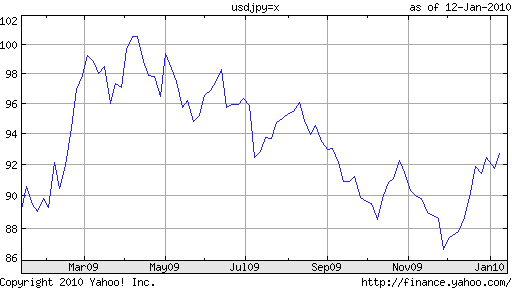

This is something we saw happening during the last Japanese experiment in quantitative easing (from 2002 – 2006) and that it has the consequence, as it did for the Yen from 2005 to 2007, that the USD will have a trading parity which it would be hard to understand if this were not the case. I am also suggesting that this situation will unwind as and when the Federal Reserve start to seriously talk about withdrawing the emergency measures (both in terms of interest rates and the various forms of quantitative easing), but that this unwinding is unlikely to be extraordinarily violent, since the Japanese Yen can simply step in to plug the gap, as I am sure the Bank of Japan will not be able to raise interest rates anytime soon given the depth of the deflation problem they have. Indeed, investors will once more be able to borrow in Yen to invest in USD instruments, to the benefit of Japanese exports and the detriment of the US current account deficit, which is why I think we are in a finely balanced situation, with clear limits to movements in one direction or another.

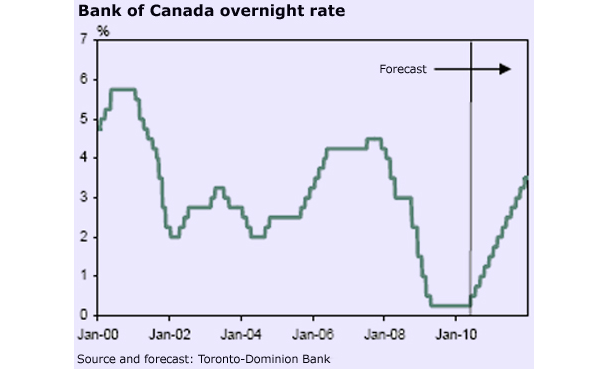

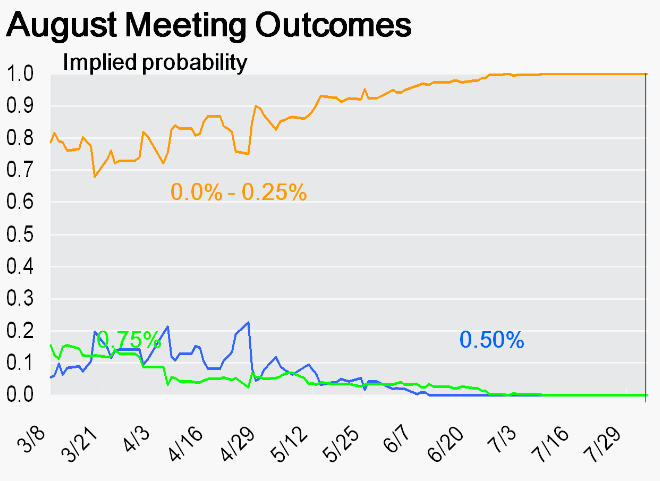

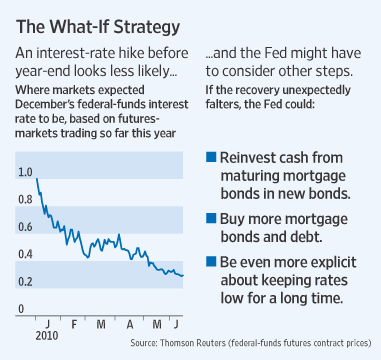

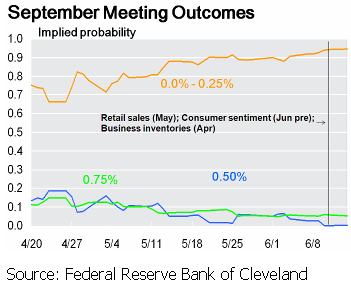

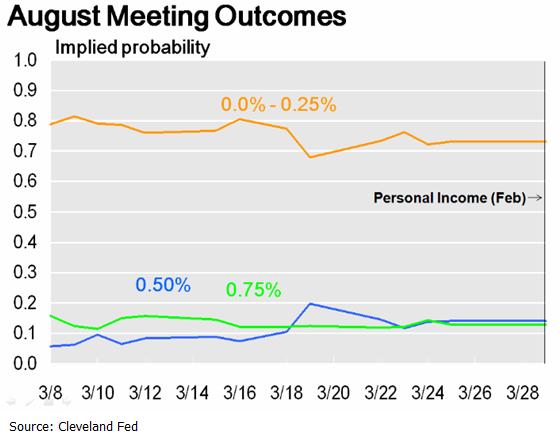

Forex Blog: In the same post, you suggested that the Fed will be the first to raise interest rates. Why do you believe this is the case? How will this affect the Dollar carry trade?

Well, I would want to qualify this a little, becuase things are not that simple. In fact, as Claus Vistesen argues in this post, the ECB has rather “locked itself in” communicationally, and by talking up the eurozone economies they now have markets expecting clear exit road maps and even pricing in interest rate rises from the third quarter of next year. But if we look at the underlying weaknesses in some of the Eurozone economies – evidently Spain, but Italy is hardly likely to have a strong robust recovery, and the German economy needs exports and hence customers to really return to growth – it is hard to see monetary tightening being applied with any kind of vigour at the ECB, so they may move up somewhat – say to 2% – and then stop for some time.

I was also suggesting that in the short run they may do this to assist in the process of unwinding the global imbalances, since allowing the Fed to lead the world out of the monetary easing cycle would almost certainly provoke a rebound in USD, and problems for correcting the US current account deficit.

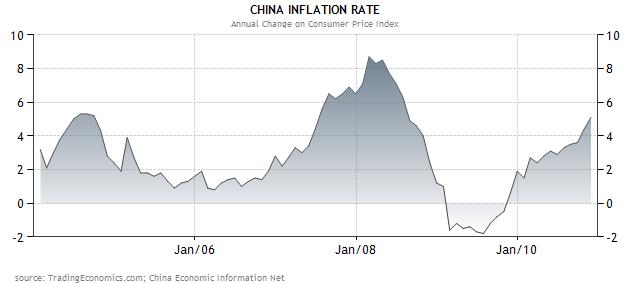

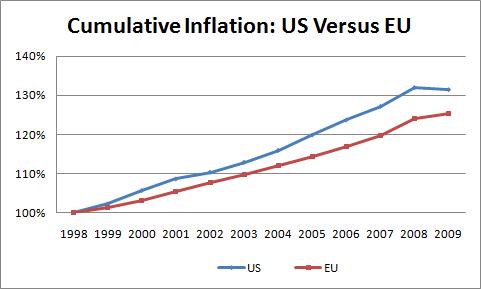

Really none of the developed economies (not even Norway) seem to be looking at the sort of really strong “V” shaped rebound some investors were anticipating, and it is more a question of who is weaker among of the weak. But if we look a little further ahead, at potential growth and inflation dynamics, then it is clear that the deflationary headwinds are stronger in Europe, while headline GDP growth may well turn out to be stronger in the US, and both these factors suggest that the Fed will at sometime be tightening faster than the ECB, in a repetition of what we saw from 2002 to 2005.

Forex Blog: You have pointed out that fiscal problems are not unique to the US. While the UK and Japan are certainly in the same fiscal boat, there seem to be plenty of examples of economies that aren’t, or at least not to the same extent, such as the EU. Do you think, then, that the long-term prospects for the Euro (especially as a global reserve currency) are necessarily brighter than for the Dollar?

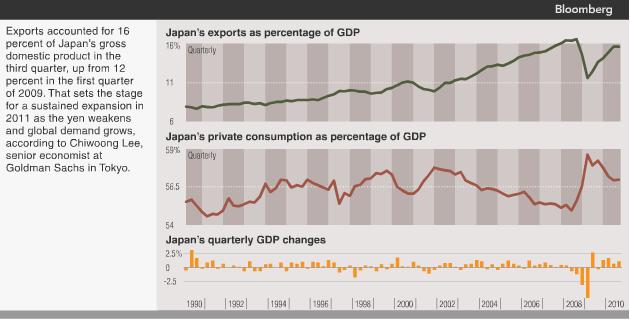

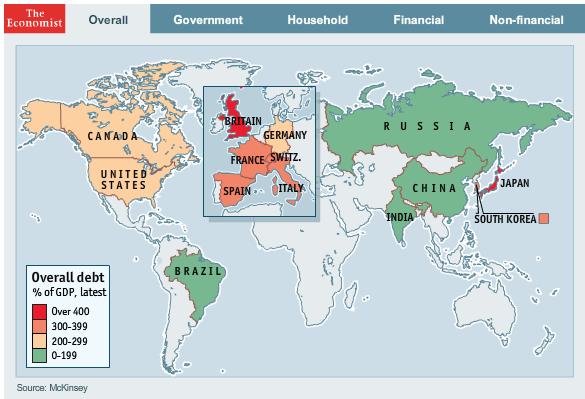

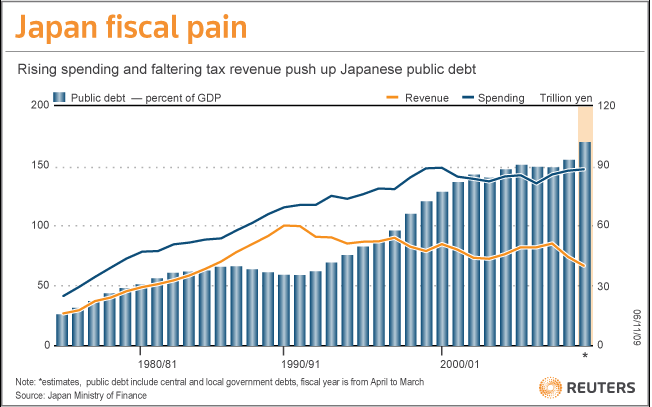

Well, actually I wouldn’t say the UK and Japan are in the same fiscal boat. Let me explain. The UK evidently has severe short term problems (as does the US) with its sovereign debt, due to the high cost of resolving the lossses produced by the current crisis. But Japan has still not resolved debt problems which were produced in the crisis of the late 1990s, and indeed both gross and net debt to GDP simply continue to rise there. So I would say – as long as they can weather the present storm – the outlook for US, UK and French sovereign debt is rather more positive than it is for Japan. Indeed in the longer term it is hard to see how Japan can resolve its problems without some kind of sovereign default. This is the problem with deflation, as nominal GDP goes down, debt to GDP simply rises and rises.

But the principal reason I am rather more positive on UK, US and French sovereign debt in the mid term is simply the underlying demographic dynamic. These countries have a lot more young people (proportionately) than the Germany’s, Japan’s and Italy’s of this world, and hence their elderly dependency ratios (which are the important thing when we come to talk about structural deficits into the future) will rise more slowly.

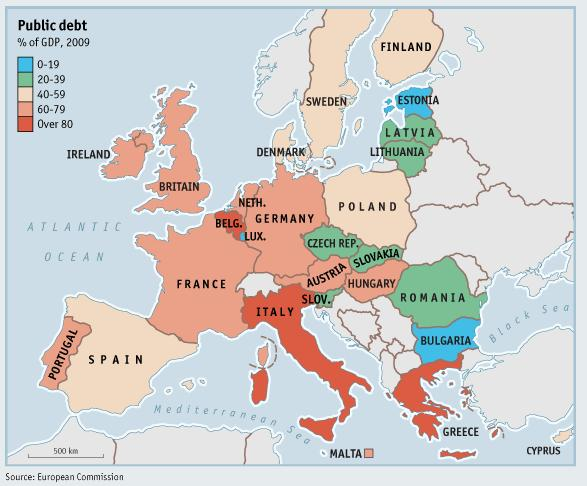

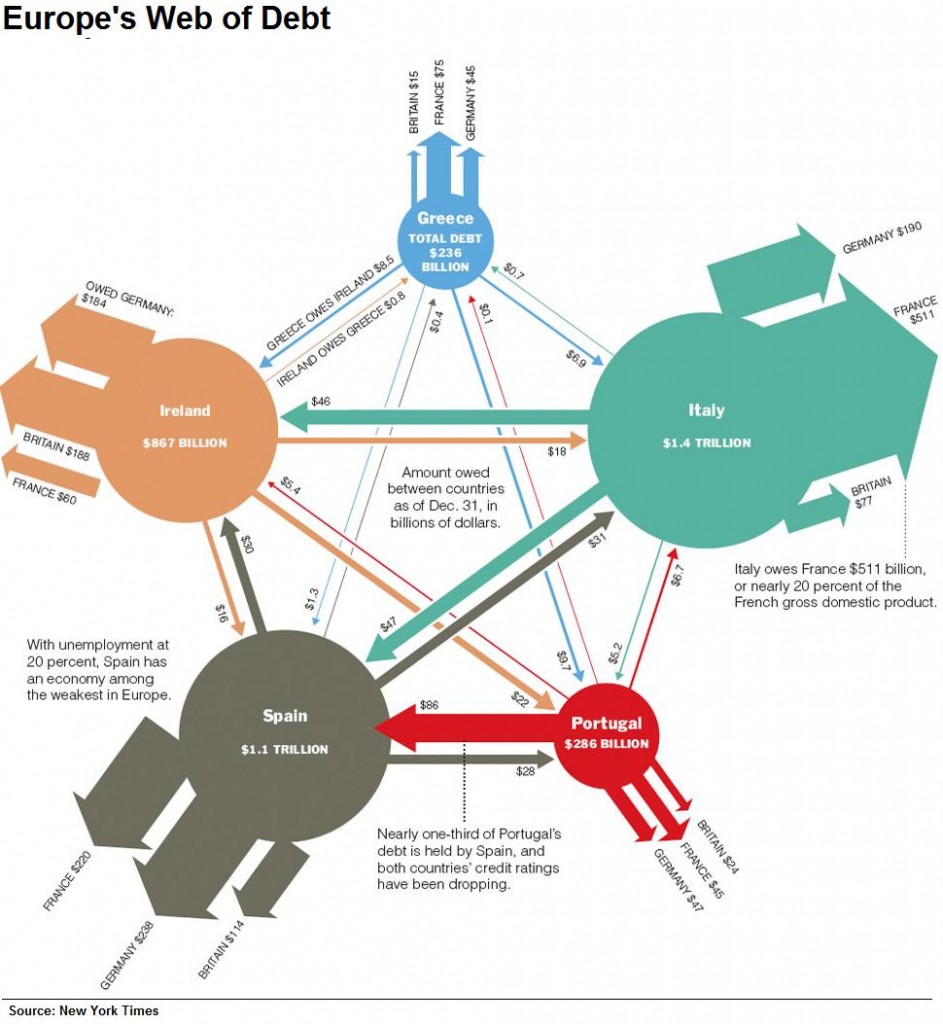

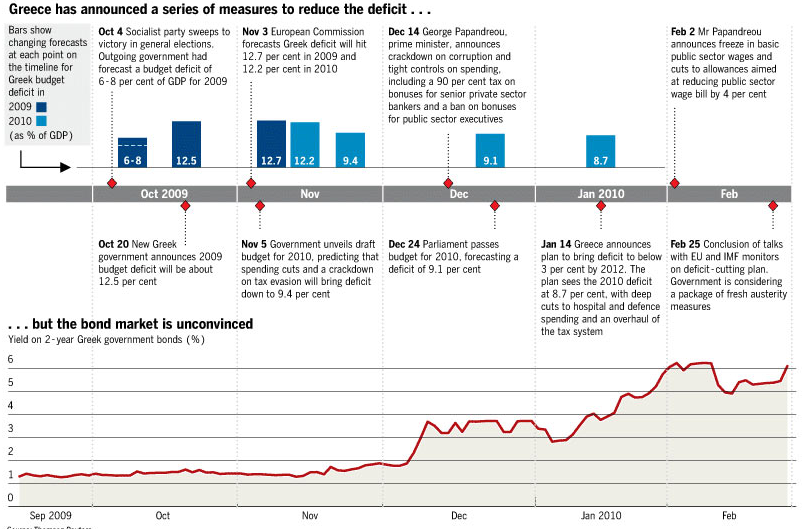

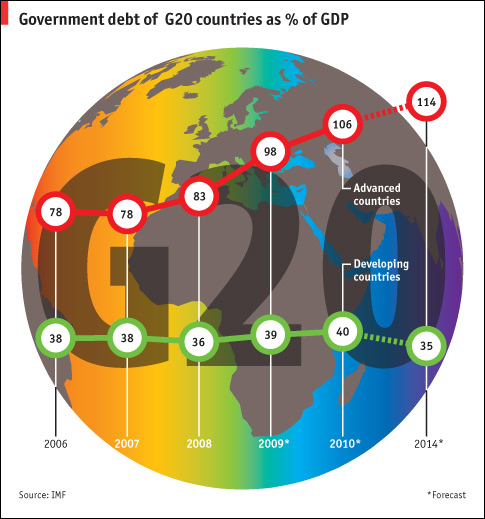

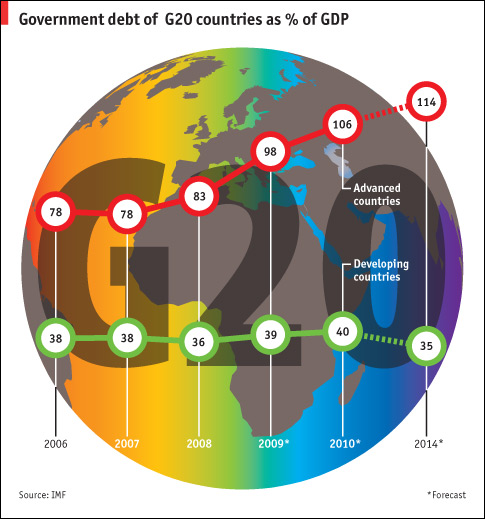

It is also important to realise that the EU – at this point at least – is not a single country in the way the US is, and indeed there is strong resistence among European citizens to the idea that it should be. So it is impossible to talk about the EU as if it were one country. That being said, the lastest forecast from the EU Commission suggests that average sovereign debt to GDP will breach the 100% threshold across the entire EU by 2014, so I would hardly call the situation promising. Basically some cases are much worse than others. In the East there are countries like Latvia and Hungary which are currently implementing IMF-lead structural transformation programmes, ut it is far from clear that these programmes will work, and sovereign debt to GDP has been rising sharply in both cases. In the South a similar problem exists, with Greek gross sovereign debt to GDP now expected by the Commission to hit 135% by 2011, and Italian debt set to increase significantly over the 110% mark. At the same time the future of government debt in Spain and Portugal is becoming increasingly uncertain. I would also point to the strong gamble Angela Merkel is making in Germany, and indeed ECB President Jean Claude Trichet singled the German case out during the last post rate-decision-meeting press conference for special mention in this regard. The future of German sovereign debt is far from clear, and markets certainly have not taken in this underlying reality.

So basically, and I think I have already explained my thinking on this in earlier questions, we have a structural difficulty, since I am sure the way out of Bretton Woods II will not be found by simply substituting the Euro for the USD. Europe is aging far more rapidly than the US, and the dependency ratio problems are consequently significantly greater.

Forex Blog: Current EU economic policy seems to be favoring government spending and exports, at the expense of investment and domestic consumption. Does this imply that the current EU economic recovery is unsustainable?

I don’t think the current EU expansion is unsustainable as such, but I do think it faces tremendous headwinds. Basically one Eurozone country stands out among the rest, France, since France has a sustainable, internal demand driven, recovery, despite all the longer term issues she faces with the structural fiscal deficit. But the story begins and end there, with France. Most of the rest of the Euro Area 16 have problems, although like Tolstoy’s unhappy families, each is problematic in its own special way. Countries like Germany and Finland are heavily export dependent, and thus have had far deeper recessions than many of the rest, while countries in the South, lead by Spain and Greece, have been running sizeable current account deficits. Since financial markets are now longer willing to fund these, and the ECB isn’t prepared to support the unsupportable forever, these economies too are now being steaily pushed towards dependence on exports for growth (and for paying down their debts), and this raises the issue of where the final end demand is going to come from. France on its own cannot supply the export surplus needs of the other 15, so external customers are needed, and this makes the value of the Euro more of an issue than it was.

Forex Blog: It seems that the reason that the the the Fed’s liquidity injections have not resulted in price inflation is because much of the funds have been plowed back into capital markets, rather than used for consumption. Given that this liquidity must at some point be pumped out by the Fed, does this imply that a “correction” is inevitable?

Yes, this is true, the global capital markets have acted as a kind of “back door” on US monetary policy, and much of the excess liquidy the Fed has been trying to pump in has simply “leaked out” via that channel. Why this should be is an interesting question in its own right, since while initially the “credit crunch” meant that funds were not available to borrow the money is now there but it is the banks who have difficulty identifying creditworthy customers given the prevailing levels of unemployment, foreclosure and bankruptcy. My feeling is that a sharp correction is not coming, unless there is a large event (Greek sovereign default, for example) in Europe or elsewhere, which leads to a sharp contraction in risk sentiment of the kind we saw after the fall of Lehman Brothers. I wouldn’t like at this point to put a figure on the probability of such an event, but the risk is evidently there.

I don’t think the risk of a correction driven by a rapid withdrawal of US liquidity is that real since I don’t think we are going to see that kind of speedy withdrawal, and even if we did, “ample liquidity” is going to be on offer over at the Bank of Japan until the cows come home. I don’t think we are going to see any precipitate removal of monetary support at the Federal Reserve, since I think exiting this situation is going to be more complicated than many imagine. The tussle which has been going on between the Japanese Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Japan over many years now may well offer a much better guide to exit issues than anything in recent US history, simply because, at least since the 1930s, the US has not been here before. Essentially it will be difficult to withdraw both fiscal and monetary support at one and the same time, but my feeling is that in the US (unlike Japan) there may well be consensus that the fiscal issue is the most pressing one, and thus this would suggest the Federal Reserve will keep monetary conditions easier for longer, simply to provide an environment in which fiscal consolidation to take place.

Forex Blog: Given the strong economic and fiscal fundamentals of Norway’s economy, do you think currency traders will begin to pay more attention to the Kroner? Do you think it could be taken up as a reserve currency by Central Banks that have become disenchanted with the Dollar?

Well, I think they already are, and evidently the Kroner has become a favoured carry currency. But equally, I doubt the Norwegian authorities would want their country to go the same way as Iceland in the longer term, so I am not sure they would welcome central banks buying Kroner in any large quantity, since this would obviously unrealistically raise the value of the currency, and lead to serious sustainability issues in the domestic manufacturing sector. Basically, as I suggested in the previous interview, I think dollar disenchantment is now likely to be seriously tempered by concerns about Euro weakness.

Forex Blog: It seems that the financial crisis has exposed some of the problems of a common economic/monetary/currency policy for the EU. What are the implications for the future of the ECB and the Euro?

Most definitely. Following Dubai a lot of attention is now focused on sovereign debt, and on who exactly is responsible for what. We should take note of the fact that the Greek government had to raise 2 billion euros in debt recently via a private placement with banks, against a backdrop of credit downgrades and steadily rising spreads. The ECB undoubtedly agreed to this move given the degree of policy coordination which must now exist behind the scenes, they are, after all, the ones who are financing the Greek banks, but it does highlight just how things have moved on in recent months. Only last year it was imagined that the being a member of the Eurozone in and of itself gave protection from the kind of financing crisis Greece increasingly now faces, and this was why only eurozone non-members, like Latvia and Hungary, were sent to the IMF. Now it is clear that the ECB could keep protecting Greece from trouble for ever and ever, but they cannot simply keep financing unsustainable external deficits and continue to retain credibility. In this sense the financial crisis has now “leaked” into the Eurozone itself. And this has implications I would have thought, for countries like Estonia, who see Eurozone membership as a “save all”, whatever the price. The difficulty is that the ECB has the capacity to fund troubled countries, but it does not have the power to enforce changes.

The problem of Europe’s institutional structures was highlighted again this week when the Latvian constitutional court ruled that pension cuts included in the recent IMF-EU package are not legal. Personally I find the decision rather significant since pension reform lies at the heart of the whole structural reform programme currently being demanded of “risky” EU states by the IMF, the EU Commission and the Credit Rating Agencies. Indeed the whole credibility of the EU’s ability to manage it’s own affairs could be called into question in this case. As Angela Merkel recently said:

“If, for example, there are problems with the Stability and Growth Pact in one country and it can only be solved by having social reforms carried out in this country, then of course the question arises, what influence does Europe have on national parliaments to see to it that Europe is not stopped…..This is going to be a very difficult task because of course national parliaments certainly don’t wish to be told what to do. We must be aware of such problems in the next few years.”

So obviously, the EU authorities badly need to plug this hole in their armour, or the entire concept of having a common monetary system can be placed at risk, Angela Merkel and Nicolas Sarkozy (who are ultimately the paymaster generals) need to have the power and authority to see to it that national parliaments do what they need to do in the common interest, and they need to get this power and authority in the coming weeks and months, and not simply in the “next few years”. And Europe’s leaders need to be aware that a crisis of sufficient proportions in any one country can very rapidly become a systemic one for the Euro, in much the same way that a problem in a key bank can lead to a crisis of confidence in a whole banking system. I do not feel a sufficient sense of urgency about this in the recent pronouncements of Europe’s leaders.

Forex Blog: So from what you are saying, there is still a risk of a resurgence in the financial crisis on Europe’s periphery. Would you say another round of financial turmoil is now inevitable?

Well the risk is certainly there, and evidently Europe’s institutional structure is in for a very testing time. But no war is ever lost before the battles are fought, although what we can say is that new and imaginative initiatives are certainly going to be needed. Sovereign risk has now spread from non-Eurozone countries like Latvia and Hungary, straight into the heart of the monetary union in cases like Greece and Spain. Mistakes have been made. As I argued in Let The East Into The Eurozone Now! in February 2009, the decision to let the Latvian authorities go ahead with their internal devaluation programme never made sense, and the three Baltic countries and Bulgaria should have been forced to devalue – and the accompanying writedowns swallowed whole – and then immediately admitted into the Eurozone as part of the emergency crisis measures. Perhaps some would feel that this lowering of the entry criteria would have damaged credibility, but as I am stressing here, leaving so many small loose cannon careering around on the lower decks can cause even more issues if matters get out of hand and contagion sets in. So it is a question of pragmatism, and being able to accept the “lesser evil”.

Unfortunately, the situation has simply been allowed to fester, and in addition the much needed change in the EU institutional structure – to allow Angela Merkel the power she is asking for to intervene in Parliaments like the Latvian, Hungarian, Greek and Spanish ones, as and when the need arises – has not been advanced, with the result that we are increasingly in danger of putting the whole future of monetary union at risk. It is never to late to act, but time is, inexorably running out. As the old English saying goes he (or she) who dithers in such situations is irrevocably lost. Caveat emptor!

1. I’d like to begin by asking if there is any significance to the

title of your blog (“Fistful of Euros”), or rather, is it only

intended to be playful?

Obviously the title is a reference to the Segio Leone film, but you

could read other connotations into it if you want. I would say the

idea was basically playful with a serious intent. Personally I agree

with Ben Bernanke that the Euro is a “great experiment”, and you could

see the blog, and the debates which surround it as one tiny part of

that experiment. As they say in Spanish, the future’s not ours to see,

que sera, sera. Certainly that “fistful of euros” has now been put

firmly on the table, and as we are about to discuss the consequences

are far from clear.

2/ You wrote a recent post outlining the US Dollar carry trade, and

how you believe that the Dollar’s decline is cyclical/temporary rather

than structural/permanent. Can you elaborate on this idea? Do you

think it’s possible that the fervor with which investors have sold off

the Dollar suggests that it could be a little of both?

Well, first of all, there is more than one thing happening here, so I

would definitely agree from the outset, there are both cyclical and

structural elements in play. Structurally, the architecture of Bretton

Woods II is creaking round the edges, and in the longer run we are

looking at a relative decline in the dollar, but as Keynes reminded

us, in the long run we are all dead, while as I noted in the Afoe

post, news of the early demise of the dollar is surely vastly

overstated.

Put another way, while Bretton Woods II has surely seen its best days,

till we have some idea what can replace it it is hard to see a major

structural adjustment in the dollar. Europe’s economies are not strong

enough for the Euro to simply step into the hole left by the dollar,

the Chinese, as we know, are reluctant to see the dollar slide too far

due to the losses they would take on dollar denominated instruments,

while the Russians seem to constantly talk the USD down, while at the

same time borrowing in that very same currency – so read this as you

will. Personally, I cannot envisage a long term and durable

alternative to the current set-up that doesn’t involve the Rupee and

the Real, but these currencies are surely not ready for this kind of

role at this point.

So we will stagger on.

On the cyclical side, what I am arguing is that for the time being the

US has stepped in where Japan used to be, as one side of your carry

pair of choice, since base money has been pumped up massively while

there is little demand from consumers for further indebtedness, so the

broader monetary aggregates haven’t risen in tandem, leaving large

pools of liquidity which can simply leak out of the back door. That

is, it may well be one of the perverse consequences of the Fed

monetary easing policy that it finances consumption elsewhere – in

Norway, or Australia, or South Africa, or Brazil, or India – but not

directly inside the US.

This is something we saw happening during the last Japanese experiment

in quantitative easing (from 2002 – 2006) and that it has the

consequence, as it did for the Yen from 2005 to 2007, that the USD

will have a trading parity which it would be hard to understand if

this were not the case. I am also suggesting that this situation will

unwind as and when the Federal Reserve start to seriously talk about

withdrawing the emergency measures (both in terms of interest rates

and the various forms of quantitative easing), but that this unwinding

is unlikely to be extraordinarily violent, since the Japanese Yen can

simply step in to plug the gap, as I am sure the Bank of Japan will

not be able to raise interest rates anytime soon given the depth of

the deflation problem they have. Indeed, investors will once more be

able to borrow in Yen to invest in USD instruments, to the benefit of

Japanese exports and the detriment of the US current account deficit,

which is why I think we are in a finely balanced situation, with clear

limits to movements in one direction or another.

3. In the same post, you suggested that the Fed will be the first to

raise interest rates. Why do you believe this is the case? How will

this affect the Dollar carry trade?

Well, I would want to qualify this a little, becuase things are not

that simple. In fact, as Claus Vistesen argues in this post

http://clausvistesen.squarespace.com/alphasources-blog/2009/11/13/random-shots.html

the ECB has rather “locked itself in” communicationally, and by

talking up the eurozone economies they now have markets expecting

clear exit road maps and even pricing in interest rate rises from the

third quarter of next year. But if we look at the underlying

weaknesses in some of the Eurozone economies – evidently Spain, but

Italy is hardly likely to have a strong robust recovery, and the

German economy needs exports and hence customers to really return to

growth – it is hard to see monetary tightening being applied with any

kind of vigour at the ECB, so they may move up somewhat – say to 2% –

and then stop for some time.

I was also suggesting that in the short run they may do this to assist

in the process of unwinding the global imbalances, since allowing the

Fed to lead the world out of the monetary easing cycle would almost

certainly provoke a rebound in USD, and problems for correcting the US

current account deficit.

Really none of the developed economies (not even Norway) seem to be

looking at the sort of really strong “V” shaped rebound some investors

were anticipating, and it is more a question of who is weaker among of

the weak. But if we look a little further ahead, at potential growth

and inflation dynamics, then it is clear that the deflationary

headwinds are stronger in Europe, while headline GDP growth may well

turn out to be stronger in the US, and both these factors suggest that

the Fed will at sometime be tightening faster than the ECB, in a

repetition of what we saw from 2002 to 2005.

4. You have pointed out that fiscal problems are not unique to the

US. While the UK and Japan are certainly in the same fiscal boat,

there seem to be plenty of examples of economies that aren’t, or at

least not to the same extent, such as the EU. Do you think, then, that

the long-term prospects for the Euro (especially as a global reserve

currency) are necessarily brighter than for the Dollar?

Well, actually I wouldn’t say the UK and Japan are in the same fiscal

boat. Let me explain. The UK evidently has severe short term problems

(as does the US) with its sovereign debt, due to the high cost of

resolving the lossses produced by the current crisis. But Japan has

still not resolved debt problems which were produced in the crisis of

the late 1990s, and indeed both gross and net debt to GDP simply

continue to rise there. So I would say – as long as they can weather

the present storm – the outlook for US, UK and French sovereign debt

is rather more positive than it is for Japan. Indeed in the longer

term it is hard to see how Japan can resolve its problems without some

kind of sovereign default. This is the problem with deflation, as

nominal GDP goes down, debt to GDP simply rises and rises.

But the principal reason I am rather more positive on UK, US and

French sovereign debt in the mid term is simply the underlying

demographic dynamic. These countries have a lot more young people

(proportionately) than the Germany’s, Japan’s and Italy’s of this

world, and hence their elderly dependency ratios (which are the

important thing when we come to talk about structural deficits into

the future) will rise more slowly.

It is also important to realise that the EU – at this point at least –

is not a single country in the way the US is, and indeed there is

strong resistence among European citizens to the idea that it should

be. So it is impossible to talk about the EU as if it were one

country. That being said, the lastest forecast from the EU Commission

suggests that average sovereign debt to GDP will breach the 100%

threshold across the entire EU by 2014, so I would hardly call the

situation promising. Basically some cases are much worse than others.

In the East there are countries like Latvia and Hungary which are

currently implementing IMF-lead structural transformation programmes,

but it is far from clear that these programmes will work, and

sovereign debt to GDP has been rising sharply in both cases. In the

South a similar problem exists, with Greek gross sovereign debt to GDP

now expected by the Commission to hit 135% by 2011, and Italian debt

set to increase significantly over the 110% mark. At the same time

the future of government debt in Spain and Portugal is becoming

increasingly uncertain. I would also point to the strong gamble Angela

Merkel is making in Germany, and indeed ECB President Jean Claude

Trichet singled the German case out during the last post

rate-decision-meeting press conference for special mention in this

regard. The future of German sovereign debt is far from clear, and

markets certainly have not taken in this underlying reality.

So basically, and I think I have already explained my thinking on this

in earlier questions, we have a structural difficulty, since I am sure

the way out of Bretton Woods II will not be found by simply

substituting the Euro for the USD. Europe is aging far more rapidly

than the US, and the dependency ratio problems are consequently

significantly greater.

1. Current EU economic policy seems to be favoring government spending and exports, at the expense of investment and domestic consumption. Does this imply that the current EU economic recovery is unsustainable?

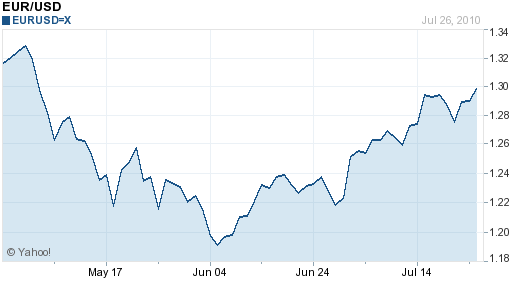

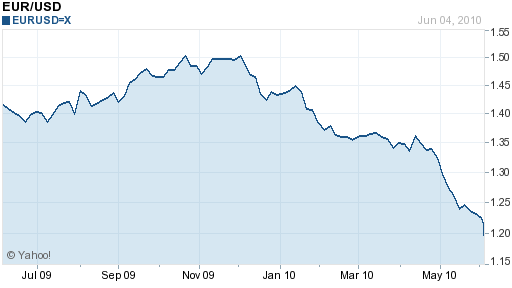

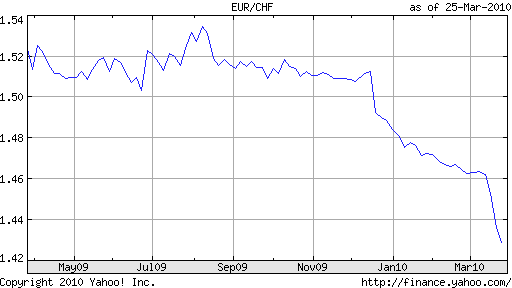

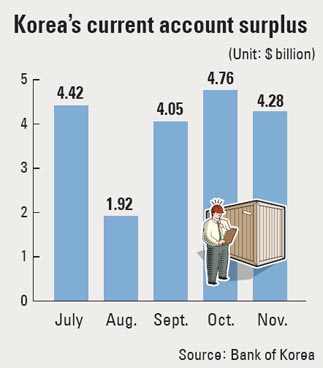

I don’t think the current EU expansion is unsustainable as such, but I do think it faces tremendous headwinds. Basically one Eurozone country stands out among the rest, France, since France has a sustainable, internal demand driven, recovery, despite all the longer term issues she faces with the structural fiscal deficit. But the story begins and end there, with France. Most of the rest of the Euro Area 16 have problems, although like Tolstoy’s unhappy families, each is problematic in its own special way. Countries like Germany and Finland are heavily export dependent, and thus have had far deeper recessions than many of the rest, while countries in the South, lead by Spain and Greece, have been running sizeable current account deficits. Since financial markets are now longer willing to fund these, and the ECB isn’t prepared to support the unsupportable forever, these economies too are now being steaily pushed towards dependence on exports for growth (and for paying down their debts), and this raises the issue of where the final end demand is going to come from. France on its own cannot supply the export surplus needs of the other 15, so external customers are needed, and this makes the value of the Euro more of an issue than it was.

2. It seems that the reason that the the the Fed’s liquidity injections have not resulted in price inflation is because much of the funds have been plowed back into capital markets, rather than used for consumption. Given that this liquidity must at some point be pumped out by the Fed, does this imply that a “correction” is inevitable?

Yes, this is true, the global capital markets have acted as a kind of “back door” on US monetary policy, and much of the excess liquidy the Fed has been trying to pump in has simply “leaked out” via that channel. Why this should be is an interesting question in its own right, since while initially the “credit crunch” meant that funds were not available to borrow the money is now there but it is the banks who have difficulty identifying creditworthy customers given the prevailing levels of unemployment, foreclosure and bankruptcy. My feeling is that a sharp correction is not coming, unless there is a large event (Greek sovereign default, for example) in Europe or elsewhere, which leads to a sharp contraction in risk sentiment of the kind we saw after the fall of Lehman Brothers. I wouldn’t like at this point to put a figure on the probability of such an event, but the risk is evidently there.

I don’t think the risk of a correction driven by a rapid withdrawal of US liquidity is that real since I don’t think we are going to see that kind of speedy withdrawal, and even if we did, “ample liquidity” is going to be on offer over at the Bank of Japan until the cows come home. I don’t think we are going to see any precipitate removal of monetary support at the Federal Reserve, since I think exiting this situation is going to be more complicated than many imagine. The tussle which has been going on between the Japanese Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Japan over many years now may well offer a much better guide to exit issues than anything in recent US history, simply because, at least since the 1930s, the US has not been here before. Essentially it will be difficult to withdraw both fiscal and monetary support at one and the same time, but my feeling is that in the US (unlike Japan) there may well be consensus that the fiscal issue is the most pressing one, and thus this would suggest the Federal Reserve will keep monetary conditions easier for longer, simply to provide an environment in which fiscal consolidation to take place.

3. Given the strong economic and fiscal fundamentals of Norway’s economy, do you think currency traders will begin to pay more attention to the Kroner? Do you think it could be taken up as a reserve currency by Central Banks that have become disenchanted with the Dollar?

Well, I think they already are, and evidently the Kroner has become a favoured carry currency. But equally, I doubt the Norwegian authorities would want their country to go the same way as Iceland in the longer term, so I am not sure they would welcome central banks buying Kroner in any large quantity, since this would obviously unrealistically raise the value of the currency, and lead to serious sustainability issues in the domestic manufacturing sector. Basically, as I suggested in the previous interview, I think dollar disenchantment is now likely to be seriously tempered by concerns about Euro weakness.

3. It seems that the financial crisis has exposed some of the problems of a common economic/monetary/currency policy for the EU. What are the implications for the future of the ECB and the Euro?

Most definitely. Following Dubai a lot of attention is now focused on sovereign debt, and on who exactly is responsible for what. We should take note of the fact that the Greek government had to raise 2 billion euros in debt recently via a private placement with banks, against a backdrop of credit downgrades and steadily rising spreads. The ECB undoubtedly agreed to this move given the degree of policy coordination which must now exist behind the scenes, they are, after all, the ones who are financing the Greek banks, but it does highlight just how things have moved on in recent months. Only last year it was imagined that the being a member of the Eurozone in and of itself gave protection from the kind of financing crisis Greece increasingly now faces, and this was why only eurozone non-members, like Latvia and Hungary, were sent to the IMF. Now it is clear that the ECB could keep protecting Greece from trouble for ever and ever, but they cannot simply keep financing unsustainable external deficits and continue to retain credibility. In this sense the financial crisis has now “leaked” into the Eurozone itself. And this has implications I would have thought, for countries like Estonia, who see Eurozone membership as a “save all”, whatever the price. The difficulty is that the ECB has the capacity to fund troubled countries, but it does not have the power to enforce changes.

The problem of Europe’s institutional structures was highlighted again this week when the Latvian constitutional court ruled that pension cuts included in the recent IMF-EU package are not legal. Personally I find the decision rather significant since pension reform lies at the heart of the whole structural reform programme currently being demanded of “risky” EU states by the IMF, the EU Commission and the Credit Rating Agencies. Indeed the whole credibility of the EU’s ability to manage it’s own affairs could be called into question in this case. As Angela Merkel recently said:

“If, for example, there are problems with the Stability and Growth Pact in one country and it can only be solved by having social reforms carried out in this country, then of course the question arises, what influence does Europe have on national parliaments to see to it that Europe is not stopped…..This is going to be a very difficult task because of course national parliaments certainly don’t wish to be told what to do. We must be aware of such problems in the next few years.”

So obviously, the EU authorities badly need to plug this hole in their armour, or the entire concept of having a common monetary system can be placed at risk, Angela Merkel and Nicolas Sarkozy (who are ultimately the paymaster generals) need to have the power and authority to see to it that national parliaments do what they need to do in the common interest, and they need to get this power and authority in the coming weeks and months, and not simply in the “next few years”. And Europe’s leaders need to be aware that a crisis of sufficient proportions in any one country can very rapidly become a systemic one for the Euro, in much the same way that a problem in a key bank can lead to a crisis of confidence in a whole banking system. I do not feel a sufficient sense of urgency about this in the recent pronouncements of Europe’s leaders.

4. So from what you are saying, there is still a risk of a resurgence in the financial crisis on Europe’s periphery. Would you say another round of financial turmoil is now inevitable?

Well the risk is certainly there, and evidently Europe’s institutional structure is in for a very testing time. But no war is ever lost before the battles are fought, although what we can say is that new and imaginative initiatives are certainly going to be needed. Sovereign risk has now spread from non-Eurozone countries like Latvia and Hungary, straight into the heart of the monetary union in cases like Greece and Spain. Mistakes have been made. As I argued in my Let The East Into The Eurozone Now! blog post (http://globaleconomydoesmatter.blogspot.com/2009/02/let-east-into-eurozone-now.html) back in February 2009, the decision to let the Latvian authorities go ahead with their internal devaluation programme never made sense, and the three Baltic countries and Bulgaria should have been forced to devalue – and the accompanying writedowns swallowed whole – and then immediately admitted into the Eurozone as part of the emergency crisis measures. Perhaps some would feel that this lowering of the entry criteria would have damaged credibility, but as I am stressing here, leaving so many small loose cannon careering around on the lower decks can cause even more issues if matters get out of hand and contagion sets in. So it is a question of pragmatism, and being able to accept the “lesser evil”.

Unfortunately, the situation has simply been allowed to fester, and in addition the much needed change in the EU institutional structure – to allow Angela Merkel the power she is asking for to intervene in Parliaments like the Latvian, Hungarian, Greek and Spanish ones, as and when the need arises – has not been advanced, with the result that we are increasingly in danger of putting the whole future of monetary union at risk. It is never to late to act, but time is, inexorably running out. As the old English saying goes he (or she) who dithers in such situations is irrevocably lost. Caveat emptor!

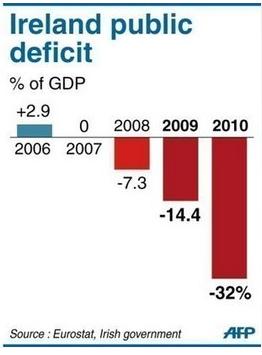

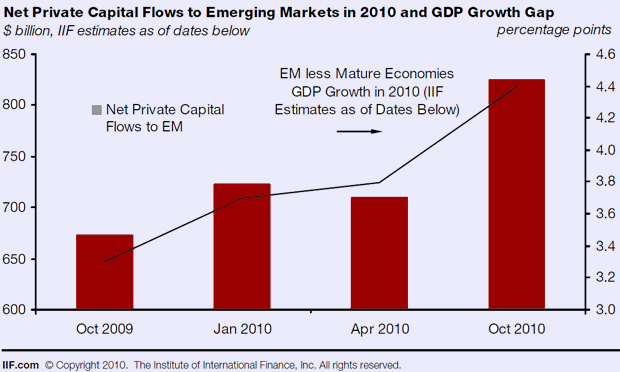

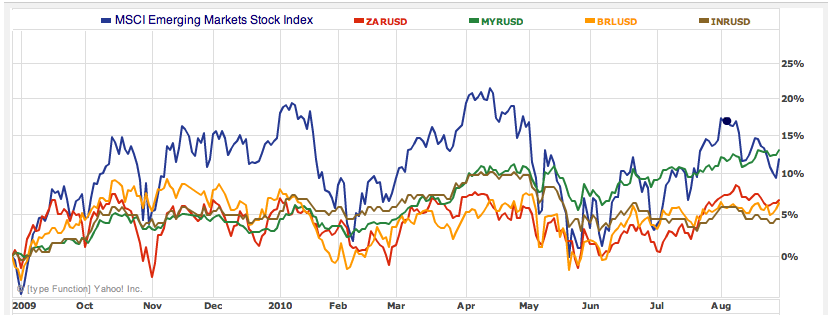

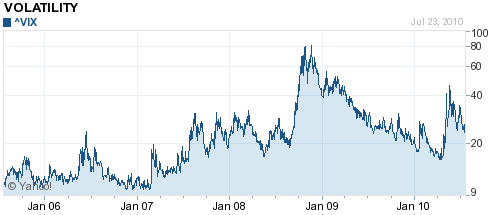

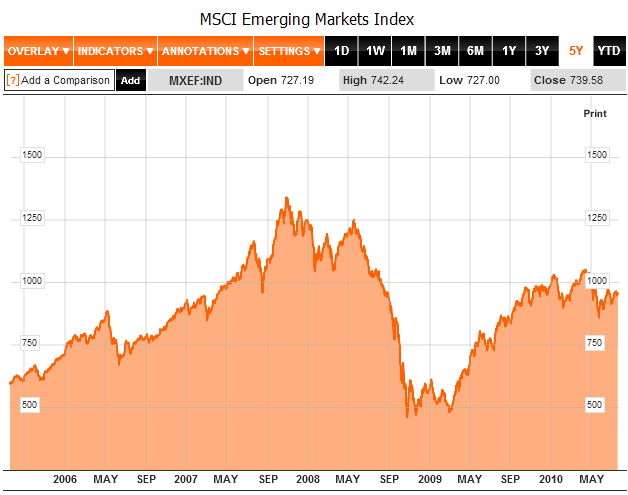

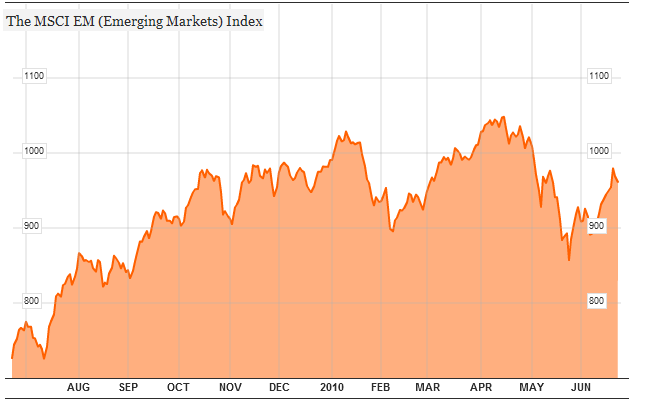

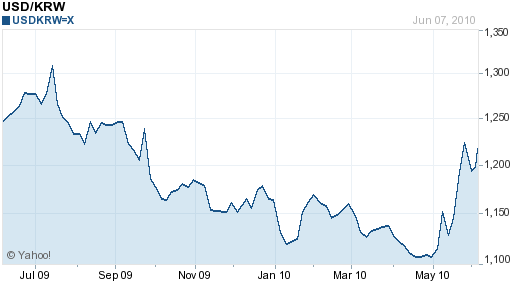

There are, however, reasons to be cautious, In the short-term, bad news and flare-ups in risk aversion invariably hit emerging market assets hardest. Regardless of what information can be gleaned from credit default spreads, the majority of investors still associate the US with safety and emerging markets with volatility. That’s why when news of Ireland’s financial troubles broke,

There are, however, reasons to be cautious, In the short-term, bad news and flare-ups in risk aversion invariably hit emerging market assets hardest. Regardless of what information can be gleaned from credit default spreads, the majority of investors still associate the US with safety and emerging markets with volatility. That’s why when news of Ireland’s financial troubles broke,

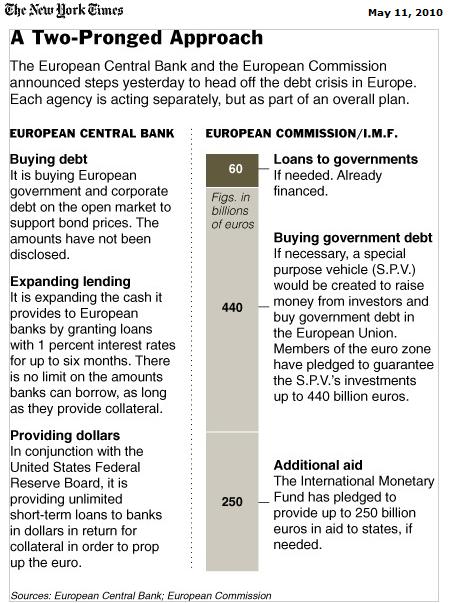

Namely, he sovereign debt crisis has officially spread beyond Greece, and “

Namely, he sovereign debt crisis has officially spread beyond Greece, and “

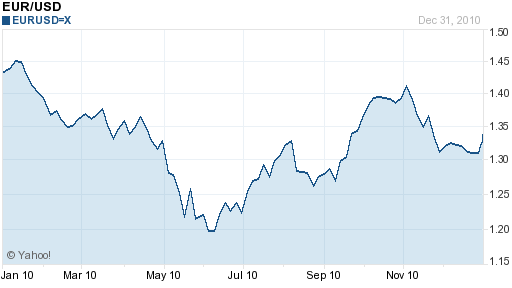

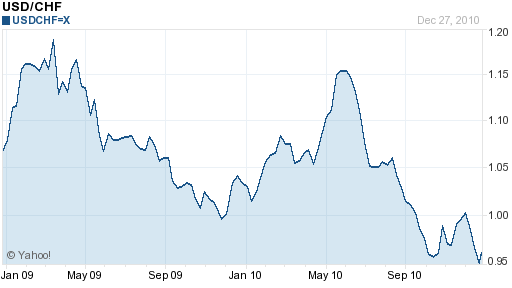

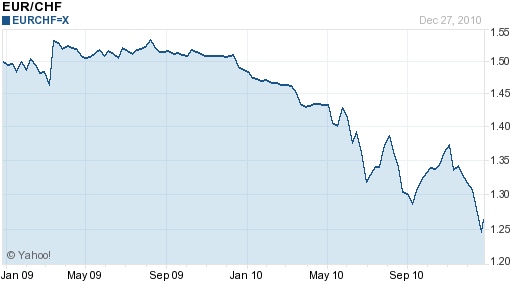

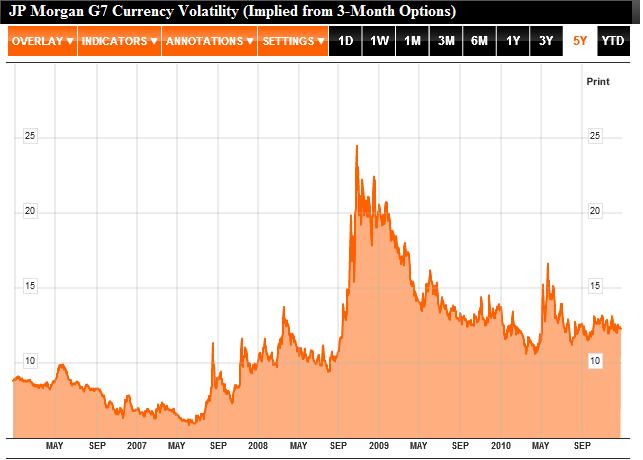

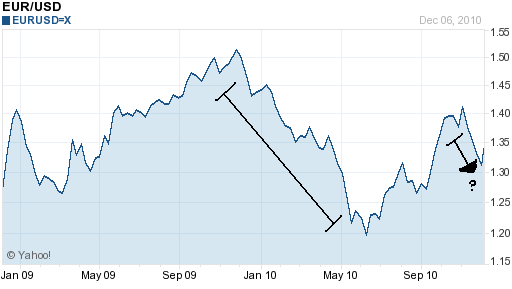

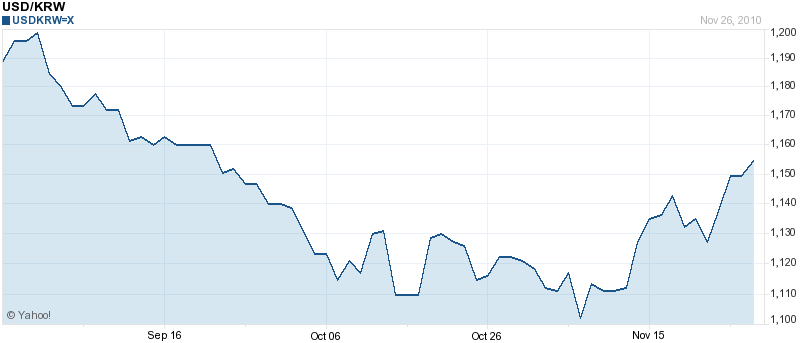

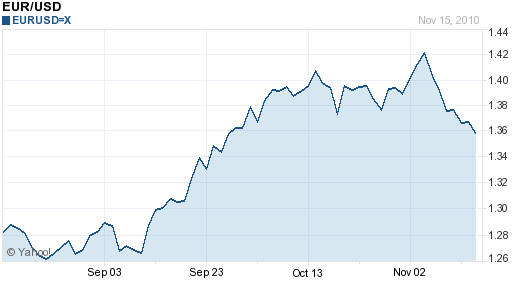

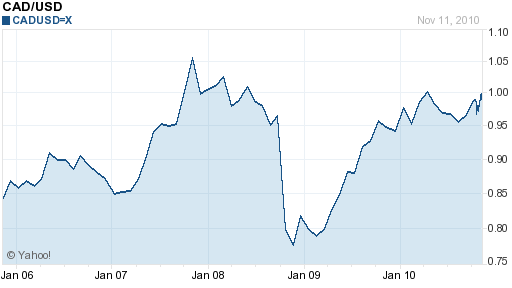

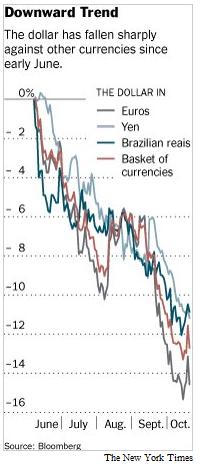

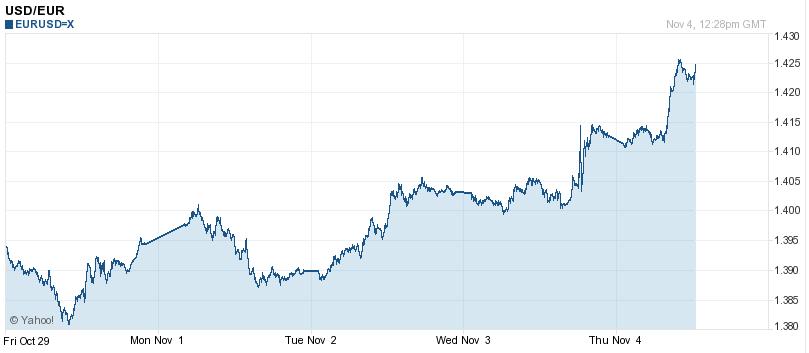

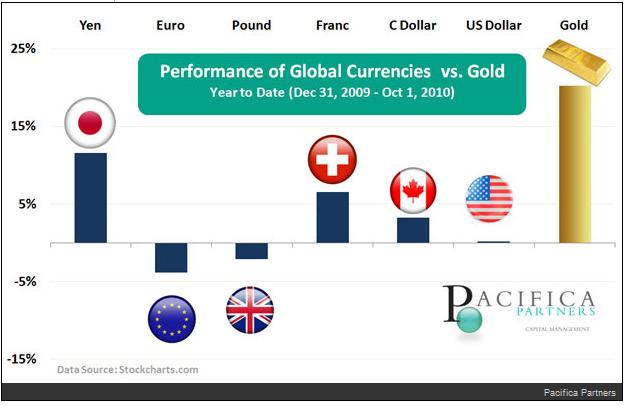

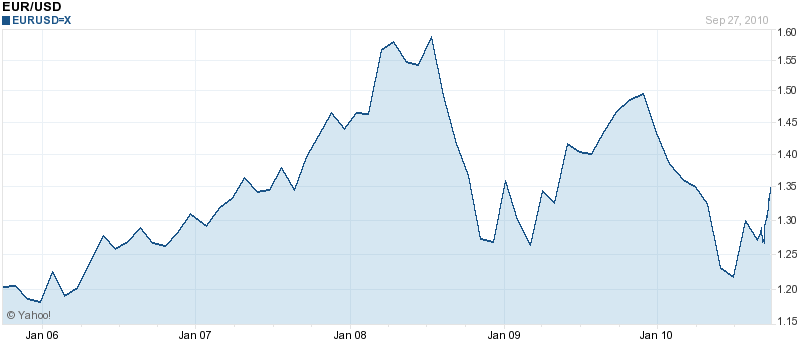

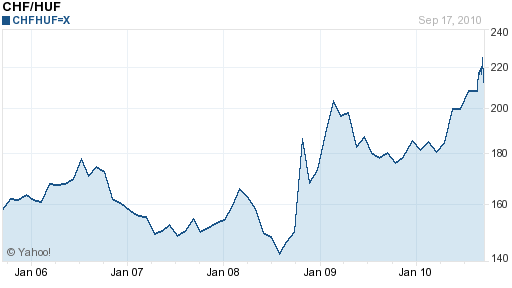

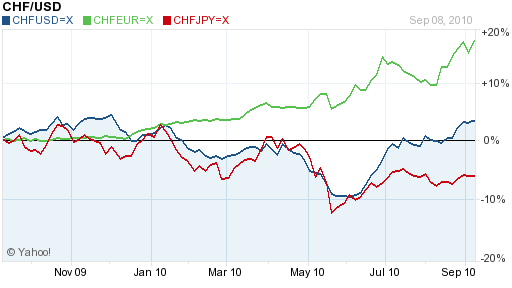

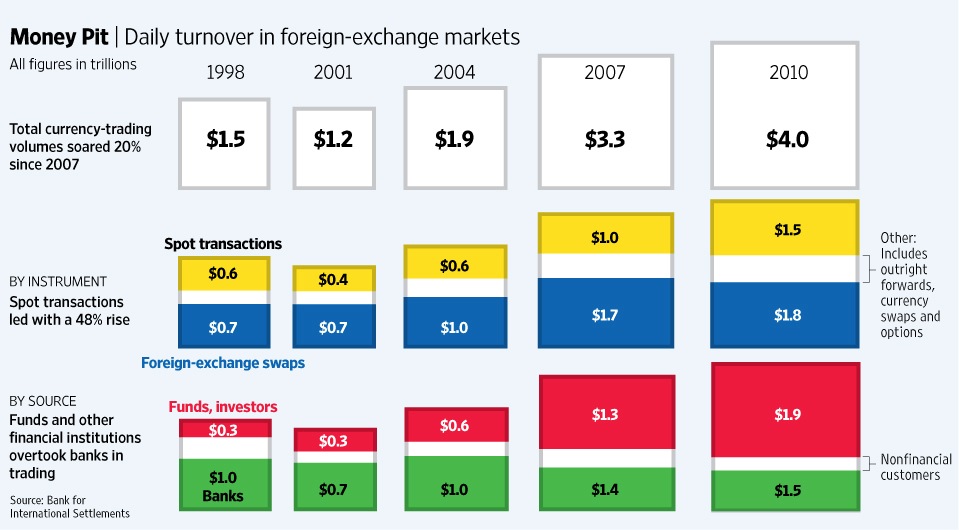

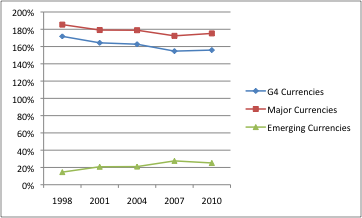

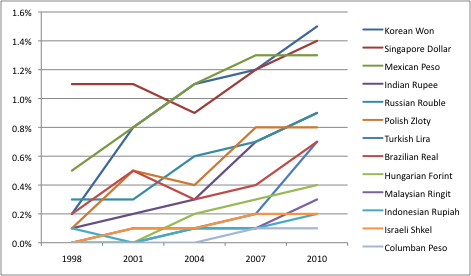

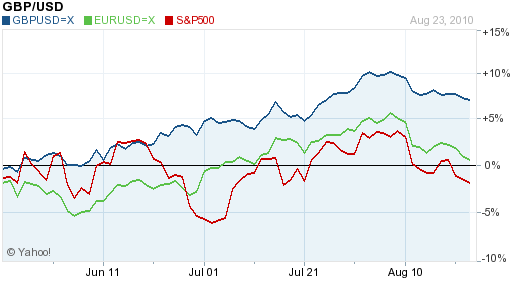

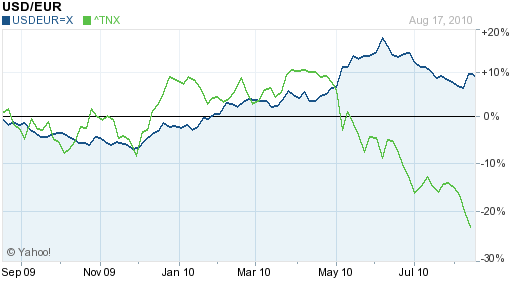

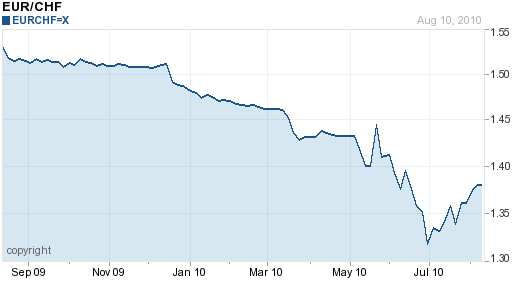

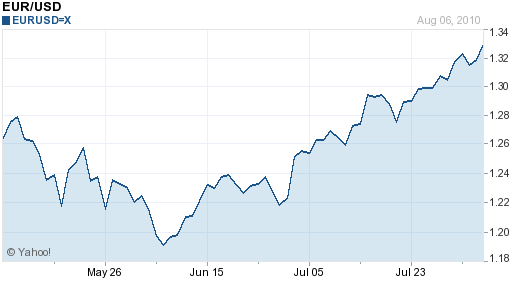

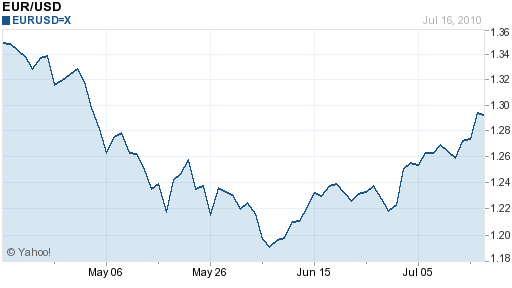

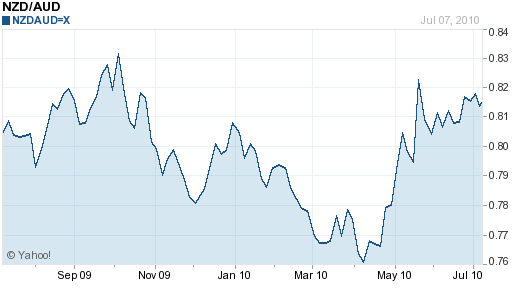

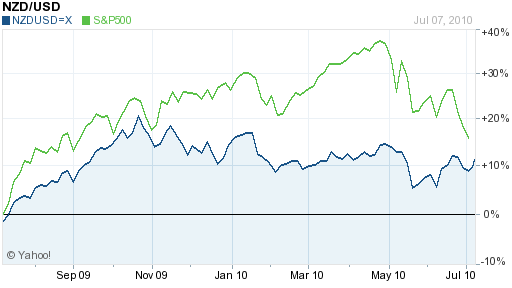

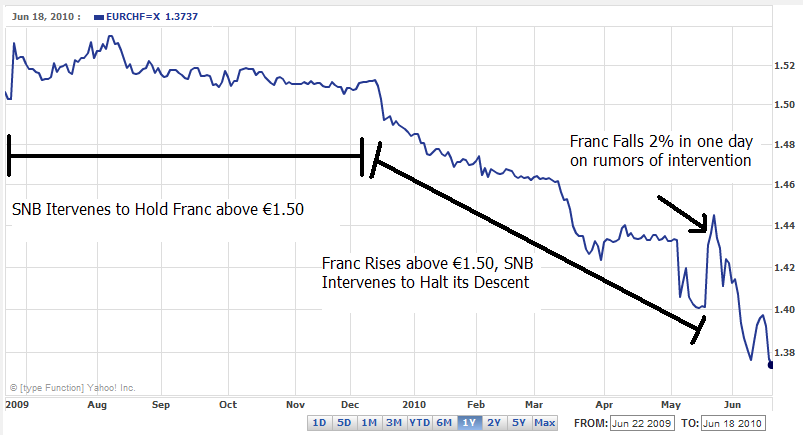

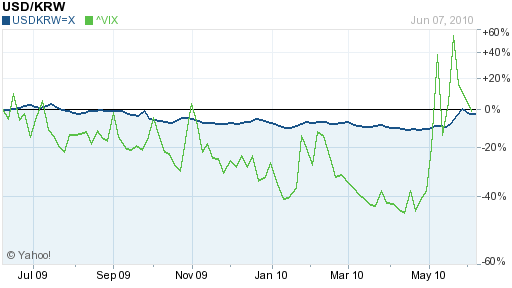

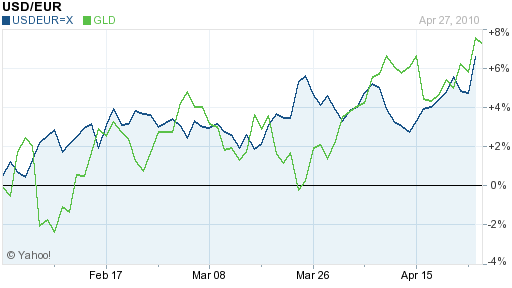

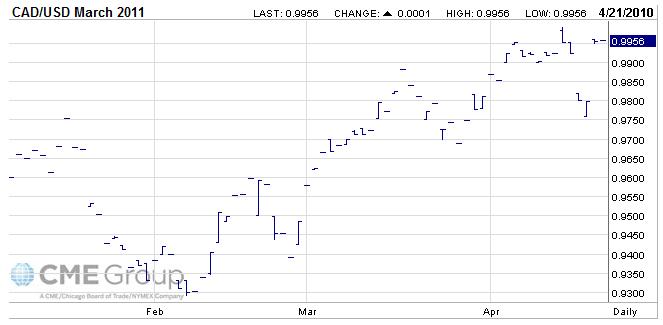

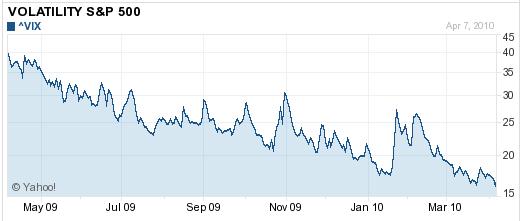

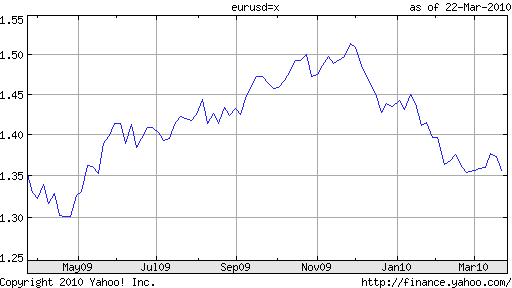

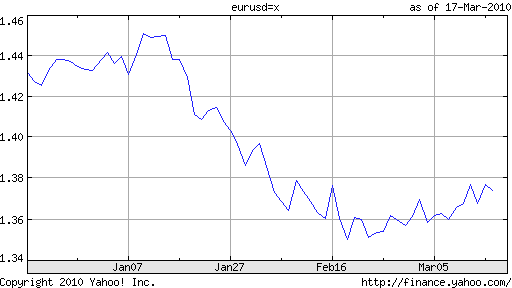

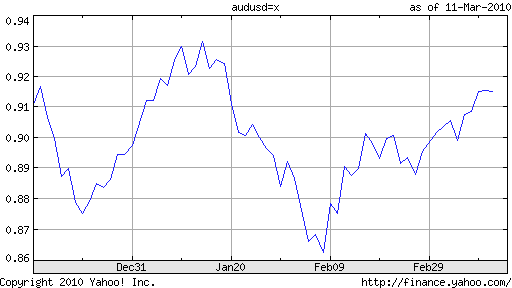

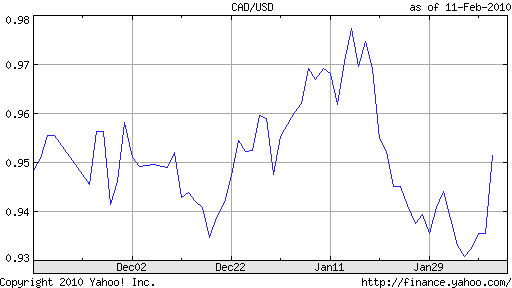

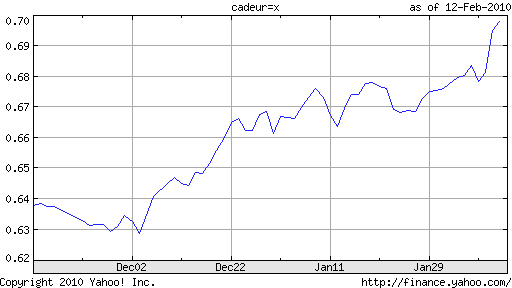

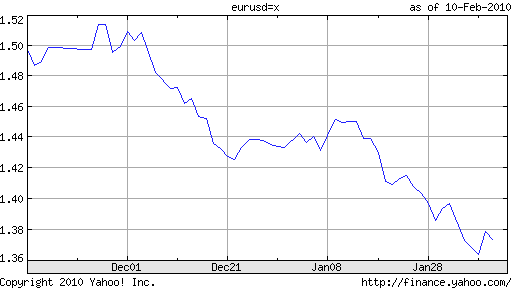

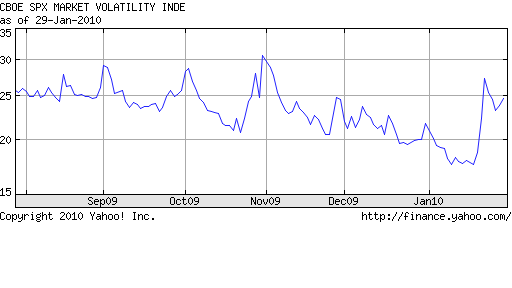

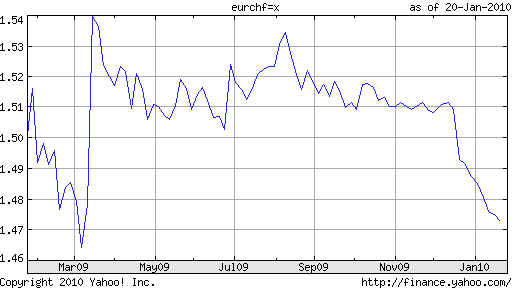

I’m sure serious technical analysts are rolling their eyes at the chart above, but the point stands that trend-following has never been easier and rarely more profitable than it is now. One fund manager summarized, “Trend-following investors are capturing the momentum in several big currency moves. You have so much uncertainty in the world now with regard to inflation or deflation, which typically makes currency markets and interest rates move. That is good for trend followers as it causes volatility, which typically creates good profits.” In other words, there is a tremendous amount happening in forex markets at the moment, and this is reflected in protracted, deep moves in currency pairs, which can change direction without notice and yet continue moving the opposite way for just as long. If you think this sounds obvious, look at historical data (5-10 years) for the majority of currency pairs: while trends have always been abundant, it was only recently that they began to last longer and became more pronounced.

I’m sure serious technical analysts are rolling their eyes at the chart above, but the point stands that trend-following has never been easier and rarely more profitable than it is now. One fund manager summarized, “Trend-following investors are capturing the momentum in several big currency moves. You have so much uncertainty in the world now with regard to inflation or deflation, which typically makes currency markets and interest rates move. That is good for trend followers as it causes volatility, which typically creates good profits.” In other words, there is a tremendous amount happening in forex markets at the moment, and this is reflected in protracted, deep moves in currency pairs, which can change direction without notice and yet continue moving the opposite way for just as long. If you think this sounds obvious, look at historical data (5-10 years) for the majority of currency pairs: while trends have always been abundant, it was only recently that they began to last longer and became more pronounced.

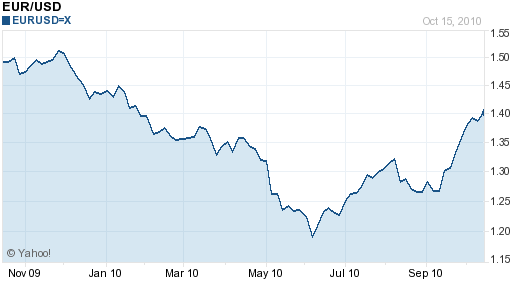

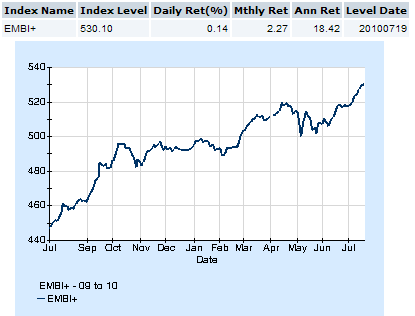

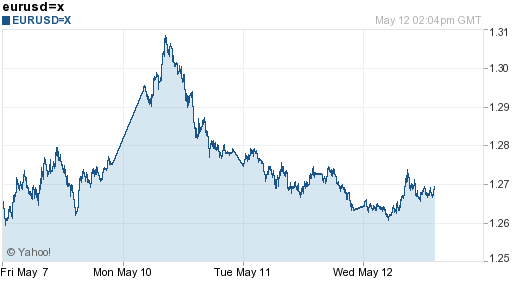

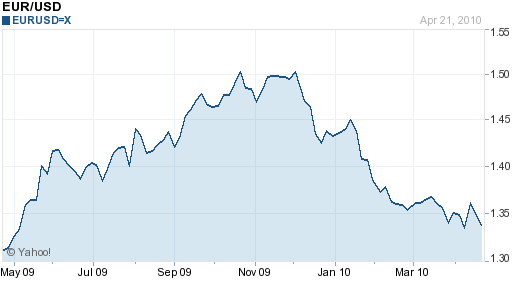

As a result, investors are rushing to reverse their short EUR/USD bets. What started as a minor correction – and inevitable backlash to the record short positions that had built up in April/May – has since turned into a flood. As a result, shorting the Dollar as part of a carry trade strategy is back in vogue. According to

As a result, investors are rushing to reverse their short EUR/USD bets. What started as a minor correction – and inevitable backlash to the record short positions that had built up in April/May – has since turned into a flood. As a result, shorting the Dollar as part of a carry trade strategy is back in vogue. According to

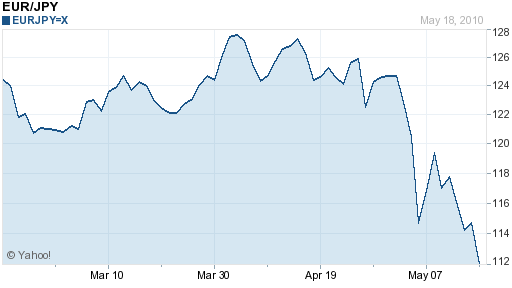

Given that only a week has passed since the bailout of Greece was formally unveiled, it’s still too early to determine whether the plan will be success. Regardless of how it ultimately plays out, though, the bailout (not too mention the concomitant crisis) is shaping up to be THE big market mover of 2009. As investors reposition their chips, some early front-runners are emerging. It might surprise you that one such leader is the Japanese Yen.

Given that only a week has passed since the bailout of Greece was formally unveiled, it’s still too early to determine whether the plan will be success. Regardless of how it ultimately plays out, though, the bailout (not too mention the concomitant crisis) is shaping up to be THE big market mover of 2009. As investors reposition their chips, some early front-runners are emerging. It might surprise you that one such leader is the Japanese Yen.

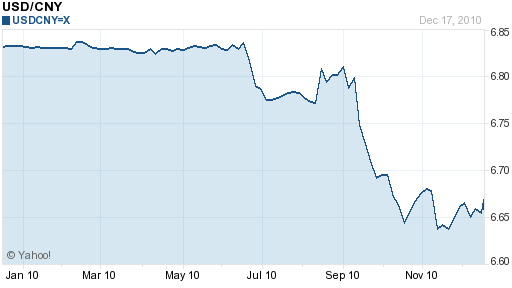

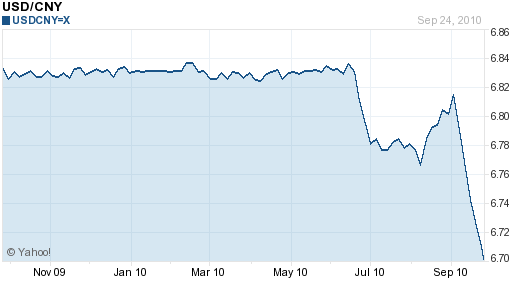

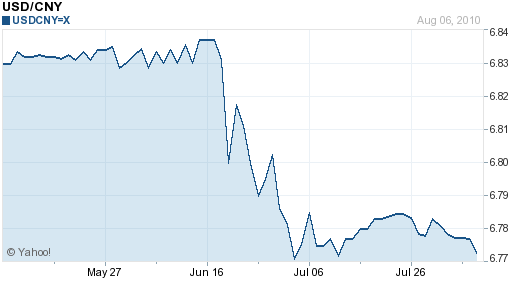

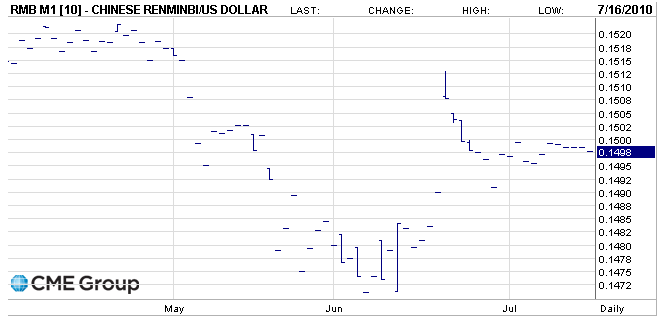

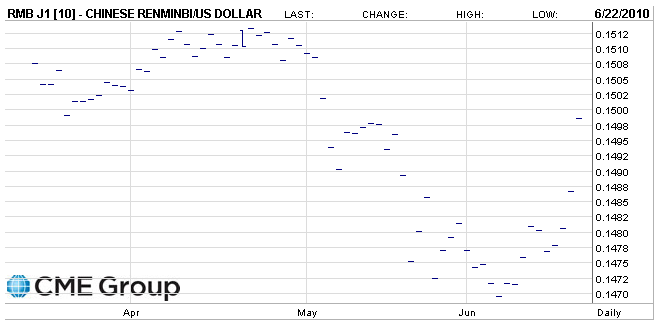

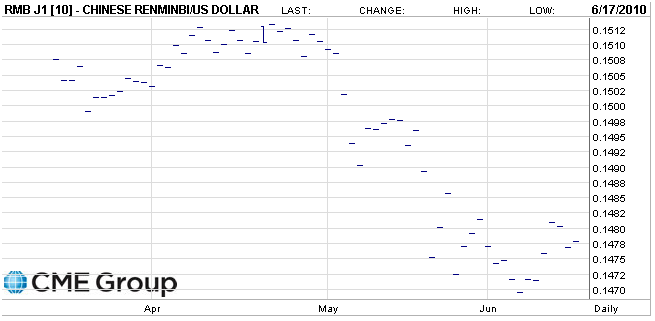

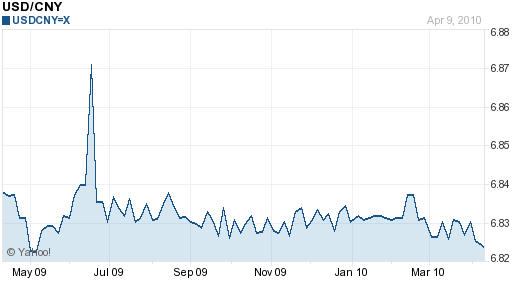

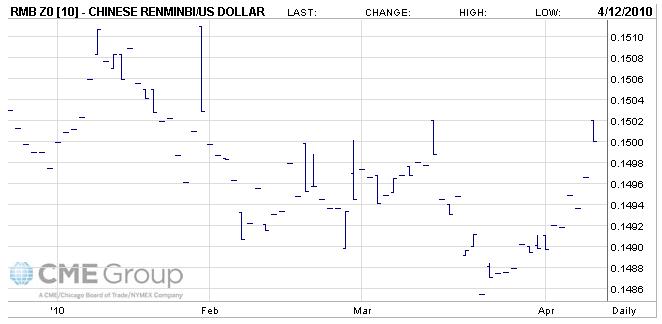

On the surface, it looks like President Obama deserves much of the credit for the sudden capitulation by China. From tire tariffs to a meeting with the Dalai Lama, he signaled that he was willing to play hard ball. As Senator Charles Schumer, one of the most vocal critics of China’s forex policy, said recently, “

On the surface, it looks like President Obama deserves much of the credit for the sudden capitulation by China. From tire tariffs to a meeting with the Dalai Lama, he signaled that he was willing to play hard ball. As Senator Charles Schumer, one of the most vocal critics of China’s forex policy, said recently, “

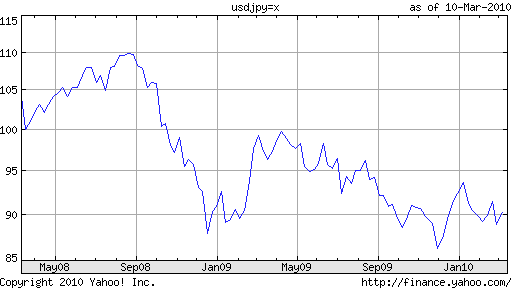

The pickup in risk aversion – as a result of the Greek debt crisis – may have delayed the return of the Yen carry trade. In January, volatility rose slightly and the Yen rallied as the safe-haven mentality set in. Personally, I find this somewhat ironic, since Japan’s debt problems are even more pronounced, and unlike Greece, it can’t count on a bailout from Greece if things really get rough. Still, the markets work in strange ways, and the fact that the Yen has benefited from the crisis is probably due to the fact that traders can’t short all currencies simultaneously.

The pickup in risk aversion – as a result of the Greek debt crisis – may have delayed the return of the Yen carry trade. In January, volatility rose slightly and the Yen rallied as the safe-haven mentality set in. Personally, I find this somewhat ironic, since Japan’s debt problems are even more pronounced, and unlike Greece, it can’t count on a bailout from Greece if things really get rough. Still, the markets work in strange ways, and the fact that the Yen has benefited from the crisis is probably due to the fact that traders can’t short all currencies simultaneously.

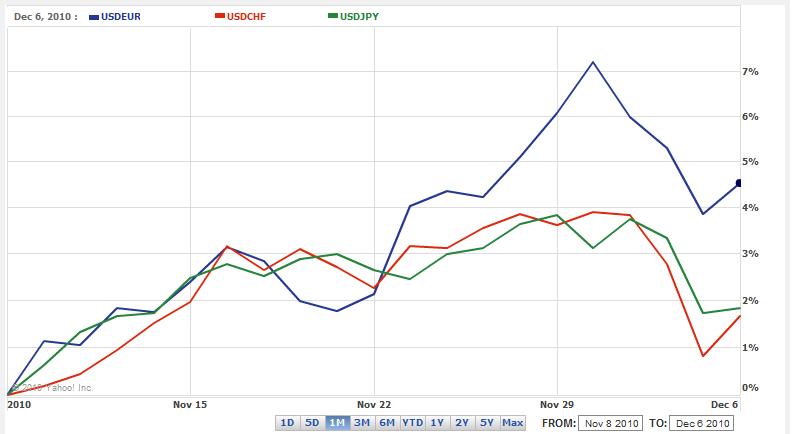

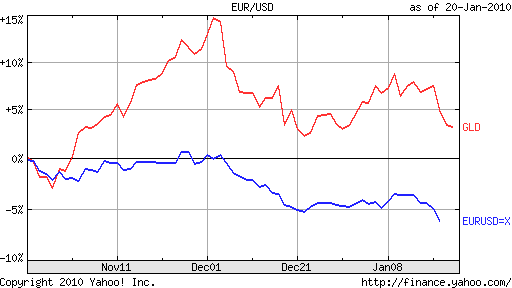

Many analysts are pointing to Friday, December 4, as the day that logic returned to the forex markets. On that day, the scheduled release of US non-farm payrolls indicated a drop in the unemployment rate and shocked investors. This was noteworthy in and of itself (because it suggests that the recession is already fading), but also because of the way it was digested by investors; for the first time in perhaps over a year, positive news was accompanied by a rise in the Dollar. Perhaps the word explosion would be a more apt characterization, as the Dollar registered a 200 basis point increase against the Euro, and the best single session performance against the Yen since 1999.

Many analysts are pointing to Friday, December 4, as the day that logic returned to the forex markets. On that day, the scheduled release of US non-farm payrolls indicated a drop in the unemployment rate and shocked investors. This was noteworthy in and of itself (because it suggests that the recession is already fading), but also because of the way it was digested by investors; for the first time in perhaps over a year, positive news was accompanied by a rise in the Dollar. Perhaps the word explosion would be a more apt characterization, as the Dollar registered a 200 basis point increase against the Euro, and the best single session performance against the Yen since 1999.

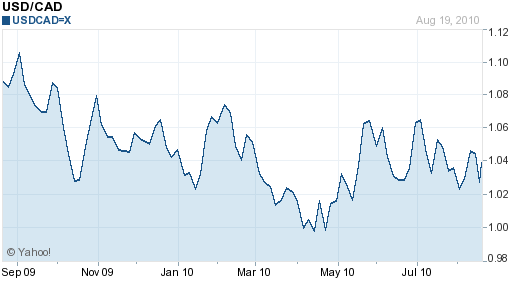

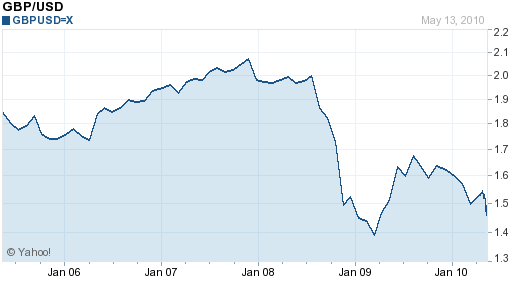

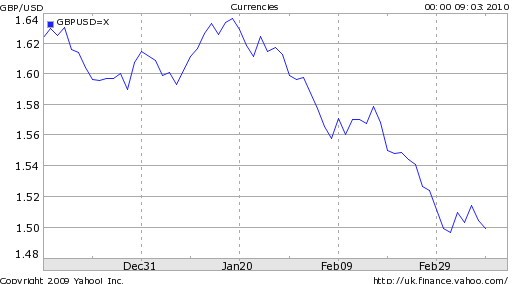

Then, there is the UK. Of all of the world’s major economies, the UK is arguably in the most precarious financial position, especially relative to its size. As

Then, there is the UK. Of all of the world’s major economies, the UK is arguably in the most precarious financial position, especially relative to its size. As