“Currency Manipulation” Will Continue, Despite G20

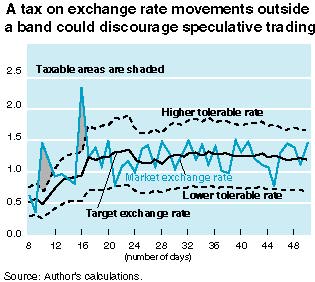

Only two years after the worst financial crisis in decades, the DJIA is now back above 12,000. Yield-hungry investors are pouring record amounts of cash into emerging markets. Commodities and food prices are rising into bubble territory. In fact, not a single meaningful reform has yet to be passed that would prevent such an event from erupting again. The EU, however, is trying to change that, with the proposed introduction of the first-ever Tobin tax on foreign exchange trades.

The campaign is being led by French President Nicolas Sarokozy, who happens to be the current Chairman of both the G8 and G20. Recently, he has used his podium for populist rants against the international financial system. To his credit, Sarkozy has done more than bluster. He is fighting to advance the idea for a minute tax on all financial transactions, with the aim of reducing volatility and raising money for cash-strapped governments.

The so-called Tobin tax was first proposed in 1971 by Nobel Laureate James Tobin. While it has always enjoyed support from a handful of leftist economists, it has never been seriously considered by any western country. In the wake of the financial crisis, however, anger towards speculation seems to be peaking, and some governments might finally have enough political capital to push forward the idea. In fact, France has already obtained the tepid support of other EU members, notably Austria. In addition, the Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee of the European Parliament has backed the idea. The EU is fighting to keep the Euro alive and its member states solvent, and it clearly resents the (perceived) role of speculators in betting on default and breakup.

Proponents of the Tobin tax generally cite the amount of revenue it could raise as its chief benefit. For example, it has been estimated that a .005% on forex transactions could raise $26 Billion worldwide, while a .05% tax on all financial transactions could generate as much as $700 Billion in revenue. Even though studies suggest that it wouldn’t do much to reduce volatility (and perhaps speculation), the fact that it shouldn’t destabilize markets is enough to satisfy some of its naysayers.

Not surprisingly, the US remains opposed to such a policy, on the grounds that it could “send misleading signals that could hamper investment to end extraction and cause production bottlenecks.” This kind of incantation rings hollow, however, and it’s clear that the biggest obstacle to its being implemented is almost certainly the bank lobby, which has insisted that a Tobin tax would “cause serious damage to this highly efficient [forex] market.”

Personally, I’m a cautious advocate of the Tobin tax. At .005%, it would levy $10 on every round-trip lot ($100,000) forex transaction. This would punish those that engage in leveraged account-churning and computerized, rapid-fire trading, without impacting those that take a longer-term approach to forex. In addition, it would impact institutional traders and investment banks (which currently monopolize all financial markets) much more than retail traders. Then again, they would probably just shift more of their trading into unregulated, private markets.

At this point, the Tobin tax is still probably a long-shot. The fact that it’s being seriously considered, however, is nothing short of remarkable.

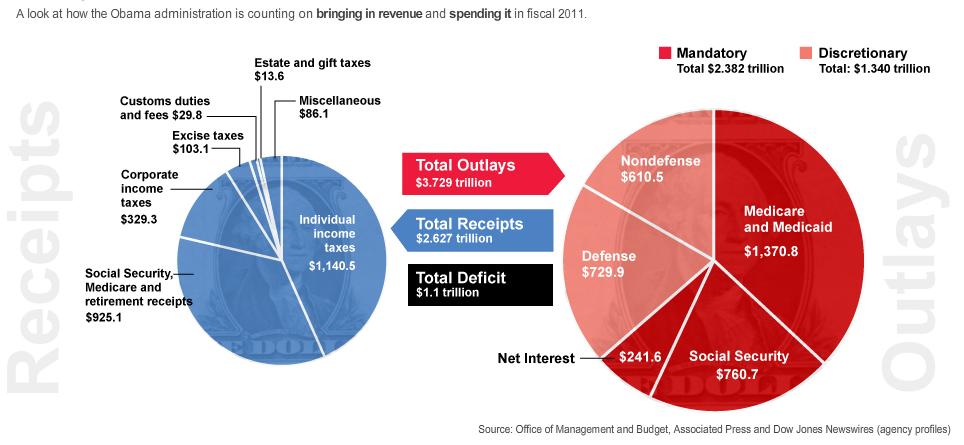

Last week, the Obama Administration released its fiscal 2012 budget to much fanfare. Unfortunately, the budget makes only a token effort to address the rising National debt, and forecasts a budget deficit of $1.1 Trillion. While the release of the budget failed to make a splash in currency markets, traders would be wise to understand its implications for the future.

The budget proposes spending of $3.7 Trillion in 2012, and forecasts receipts of only $2.6 Trillion. As usual, entitlements (Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid: $2 Trillion+), Defense ($760 Billion), and net interest on debt ($250 Billion) are projected to consume the brunt of spending. The Departments of State, Education, Energy, and Veterans Fairs will receive an increased allocation, while almost all other Departments face drastic cuts. (For more comprehensive breakdowns, the WSJ and NY Times offer excellent graphical representations of how the federal budget is funded and disbursed).

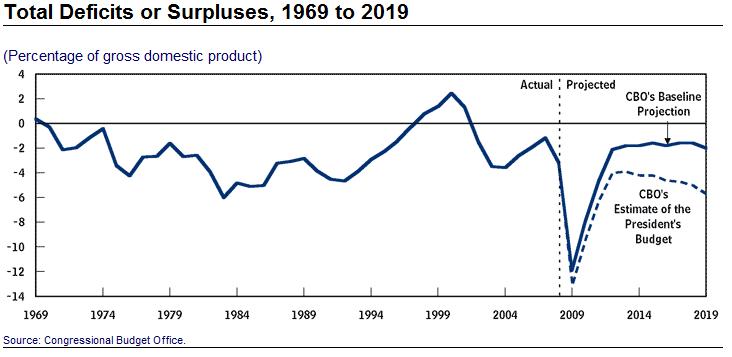

The proposed budget allows for a deficit of $1.1 Trillion (7% of GDP), which unbelievably represents a significant decrease from the $1.6 Trillion (11% of GDP) that is projected for fiscal 2011. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts the deficit to return to a more “sustainable” level of 3% of GDP beginning in 2014, which should allow the national debt to remain constant in relative terms for the following decade. Beginning in 2021, however, entitlement spending is projected to skyrocket, which would cause debt to rise similarly.

CBO projections are based on a handful of rosy assumptions. First of all, it assumes that the US economy will grow at 3%+ for the indefinite future. Second, it assumes that deficit spending can be financed at reasonable interest rates. Third, it assumes that tax receipts will rise from current lows and revert back to historical levels. Given the ongoing economic uncertainty, high unemployment rates, tax cuts, rising interest rates, the difficulty of cutting spending, etc., there is reason to believe that actual deficits will be even higher.

In fact, net interest payments on national debt will rise 33% over the next year even as Treasury rates remain at record lows. If the economic recovery gathers momentum (something that the budget is counting on), risk appetite and interest rates must rise. In addition, given that the national debt will probably double from 2009 to 2012, it seems likely that investors will demand an increased risk premium for lending to the US. On the other hand, demand for Treasury Securities continues to remain strong: “Net long-term securities transactions showed total buying of $65.9 billion in long-term U.S. securities in December, after purchases of $85.1 billion the month before.” Many Central Banks continue to be net buyers.

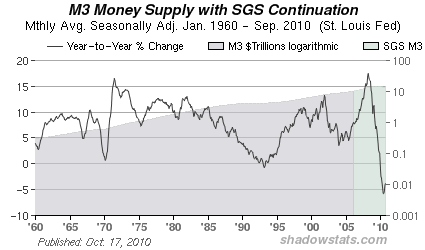

In addition, there are some commentators that think the Fed will abet the US government in deflating the real value of its debt. Since the majority of US Treasury Securities are not inflation-protected, 15 years of high inflation (~5%) would be enough to decrease the real debt burden by half. Especially when you account for “contingent obligations,” this might be the only feasible way for the government to deal with its debt burden over the long-term. Then again, higher inflation would probably drive proportional increases in yield, such that the Treasury Department would have a tough time rolling over existing debt (let alone in issuing new debt) at reasonable interest rates.

The main variable in all of this is politics. Specifically, this budget is still only a proposal. The actual budget won’t be ratified for at least another six months, and only after tense negotiations with the Republican Party. (There is also the possibility that it won’t be passed at all, which is what happened with the fiscal 2011 budget). “House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, a Virginia Republican, said his party will propose ‘very bold’ changes to entitlements in their 2012 budget resolution.” Anything short of this wouldn’t dent the projected deficits and would push Social Security / Medicare closer towards the brink of insolvency.

In the end, the deficit merely represents business as usual for the US government. Barring a double-dip recession, it probably won’t be enough to seriously impact the Dollar’s status in the short-term as preeminent global reserve currency. However, that could start to change over the next decade, as the government either takes steps or does nothing to mitigate the looming entitlements crisis. At that time, the long-term viability of the Dollar (and the financial system as we know it) will become clear.

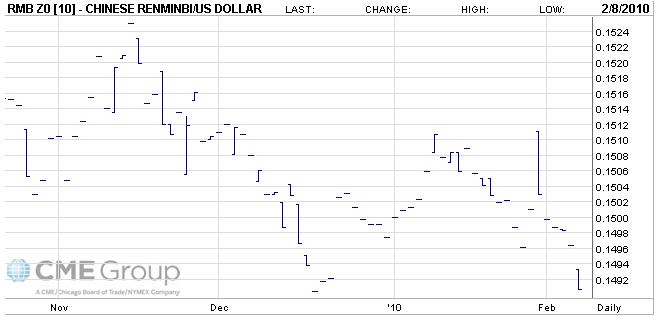

At the very end of 2010, the Chinese Yuan managed to cross the important psychological level of 6.60 USD/CNY, reaching the highest level since 1993. Moreover, analysts are unanimous in their expectation that the Chinese Yuan will continue rising in 2011, disagreeing only on the extent. Since the Yuan’s value is controlled tightly by Chinese policymakers, forecasting the Yuan requires an in-depth look at the surrounding politics.

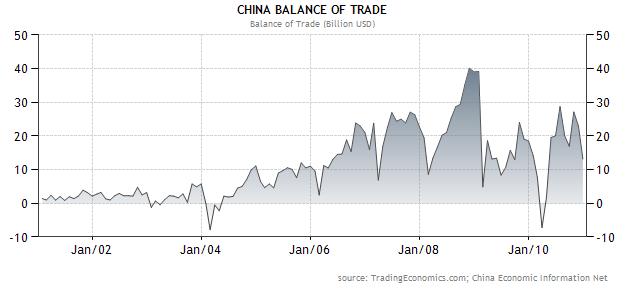

While American politicians chide it for not doing enough, the Chinese government nonetheless deserves some credit. It has allowed the Yuan to appreciate nearly 25% in total, which should be just enough to satisfy the 25-40% that was initially demanded. Meanwhile, over the last five years, China’s trade surplus has fallen dramatically, to 3.3% of GDP in 2010, compared to a peak of 11% in 2007. In fact, if you don’t include trade with the US, its surplus was basically nil this year.

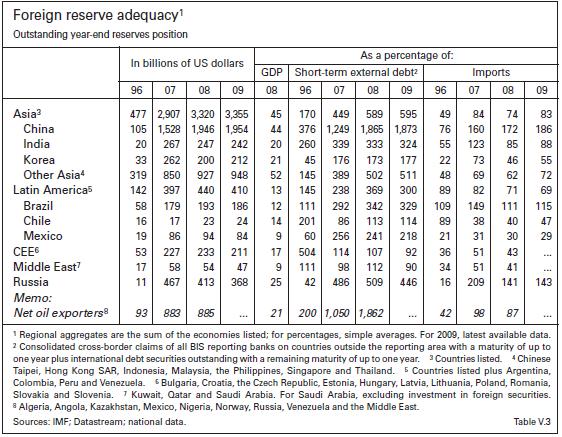

Therein lies the problem. Despite the fact that prices in Chinese exports should have risen 25% (much more if you take inflation and rising wages into account) since 2004, the China/US trade balance has remained virtually unchanged, and its current account surplus has actually widened. As a result, China’s foreign exchange reserves increased by a record amount in 2010, bringing the total to a whopping $2.9 Trillion! (Of course, these reserves should be thought of as a monetary burden rather than pure wealth, to the same extent as the US Federal Reserve Board’s Balance Sheet must one day be wound down. In the context of this discussion, however, that might be a moot point).

Therein lies the problem. Despite the fact that prices in Chinese exports should have risen 25% (much more if you take inflation and rising wages into account) since 2004, the China/US trade balance has remained virtually unchanged, and its current account surplus has actually widened. As a result, China’s foreign exchange reserves increased by a record amount in 2010, bringing the total to a whopping $2.9 Trillion! (Of course, these reserves should be thought of as a monetary burden rather than pure wealth, to the same extent as the US Federal Reserve Board’s Balance Sheet must one day be wound down. In the context of this discussion, however, that might be a moot point).

Meanwhile, China is trying to slowly tilt the structure of its economy towards domestic consumption, which is increasing by almost every measure. Its Central Bank is also slowly hiking interest rates and raising the reserve requirements of banks in order to put the brakes on economic growth and rein in inflation. Finally, it is trying to encourage internationalization of the Yuan. There now 70,000 Chinese trade companies that are permitted to settle trades in Chinese Yuan. In addition, Bank of China just announced that US customers will be able to open up Yuan-denominated accounts, and the World Bank became the latest foreign entity to issue an RMB-denominated “Dim-Sum Bond.”

There is also evidence that the Chinese Government’s top leadership – with whom the US government directly negotiates – is actually pushing for a faster appreciation of the RMB but that it faces internal opposition. According to the New York Times, “The debate over revaluing the renminbi… has not advanced much partly because of a fight between central bankers who want the currency to rise and ministers and party bosses who want to protect the vast industrial machine that depends on cheap exports for survival.” In fact, the Bank of China (PBOC) recently warned, “Factors such as the country’s trade surplus, foreign direct investment, China’s interest rate gap with Western countries, yuan appreciation expectations, and rising asset prices are likely to persist, drawing funds into the country,” while a senior Chinese lawmaker pushed back that a “rise in the yuan’s value won’t help the country to curb inflation.”

Some analysts expect a big move in the Yuan that corresponds with this week’s US visit by China’s Prime Minister, Hu Jintao. The average call, however, is for a continued, steady rise. “China’s currency will strengthen 4.9 percent to 6.28 by the end of 2011, according to the median estimate of 19 analysts in a Bloomberg survey. That’s over double the 2 percent gain projected by 12-month non-deliverable forwards.” As I wrote in my previous post on the Chinese Yuan, however, it ultimately depends on inflation – whether it keeps rising and if so, how the government chooses to tackle it.

The “currency war” is heating up, and all parties are pinning their hopes on the G20 summit in South Korea. However, this is reason to believe that the meeting will fail to achieve anything in this regard, and that the cycle of “Beggar-thy-Neighbor” currency devaluations will continue.

There have been a handful of developments since the my last analysis of the currency war. First of all, more Central Banks (and hence, more currencies) are now affected. In the last week, Argentina pledged to continue its interventions into 2011, while Taiwan, and India – among other less prominent countries – have hinted towards imminent involvement.

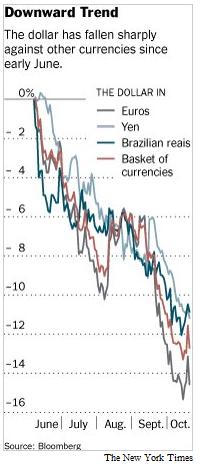

Of greater significance was the official expansion of the Fed’s Quantitative Easing Program (QE2), which at $600 Billion, will dwarf the efforts of all other Central Banks. In fact, it’s somewhat ironic that the Fed is the only Central Bank that doesn’t see its monetary easing as a form of currency intervention when you consider its impact on the Dollar and its (inadvertent?) role in “intensifying the currency war.” According to Chinese officials, “The continued and drastic U.S. dollar depreciation recently has led countries including Japan, South Korea and Thailand to intervene in the currency market,” while the Japanese Prime Minister recently accused the U.S. of pursuing a “weak-dollar policy.”

As of now, there is no indication that other industrialized countries will follow suit, though given concerns that QE2 “at the end of the day might be dampening the recovery of the euro area,” I think it’s too early to rule anything out. While the Bank of Japan similarly has stayed out of the market since its massive intervention in October, Finance Minister Yoshihiko Noda recently declared that, “I think the [Yen’s] moves yesterday were a bit one-sided. I will continue to closely monitor these moves with great interest.”

As the war reaches a climax of sorts, everyone is waiting with baited breath to see what will come out of the G20 Summit. Unfortunately, the G20 failed to achieve anything substantive at last month’s Meeting of Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, and there is little reason to believe that this month’s meeting will be any different.

In addition, the G20 is not a rule-making body like the WTO or IMF, and it has no intrinsic authority to stop participating nations from devaluing their currencies. Conference host South Korea has lamely pointed out that while ” ‘There aren’t any legal obligations‘…discussion among G20 countries would produce ‘a peer-pressure kind of effect on these countries’ that violated the deal.” Not to mention that the G20 will have no effect on the weak Dollar nor on the undervalued RMB, both of which are at the root of the currency war.

It’s really just wishful thinking that countries will come to their senses and realize that currency devaluation is self-defeating. In the end, the only thing that will stop them from intervening is to accept the futility of it: “The history of capital controls is that they don’t work in controlling foreign exchange rates.” This time around will prove to be no different, “particularly with banks already said to be offering derivatives products to get around the new taxes.” The only exception is China, which is only able to prevent the rise of the RMB because of strict controls for dealing with the inflow of capital.

In short, the “wall of money” that is pouring into emerging market economies represents a force too great to be countered by individual Central Banks. The returns offered by investing in emerging markets (even ignoring currency appreciation) are so much greater than in industrialized countries that investors will not be deterred and will only work harder to find ways around them. Ironically, to the extent that controls limit the supply of capital and boost returns, they will probably drive additional capital inflows. The more successful they are, the more they will fail. And that’s something that no new currency agreement can change.

I read a provocative piece the other day by Michael Hudson (“Why the U.S. Has Launched a New Financial World War — and How the Rest of the World Will Fight Back“), in which he argued that the ongoing currency wars are the fault of the US. Below, I’ll explain why he’s both right and wrong, and why he (and everyone else) should shut up and stop complaining.

It has become almost cliche to argue that the US, as the world’s lone hegemonic power, is also the world’s military bully. Hudson takes this argument one step further by accusing the US of using the Dollar as a basis for conducting “financial warfare.” Basically, the US Federal Reserve Bank’s Quantitative Easing and related monetary expansion programs create massive amounts of currency, the majority of which are exported to emerging market countries in the form of loans and investments. This puts upward pressure on their currencies, and rewards foreign speculators at the expense of domestic exporters.

Hudson is right that the majority of newly printed money has indeed been shifted to emerging markets, where the best returns and greatest potential for appreciation lies. Simply, the current economic and investing climate in the US is not as strong as in emerging markets. Indeed, this is why the (first) Quantitative Easing (QE) program was not very successful, and why the Fed has proposed a second round. While there is a bit of a chicken-and-egg conundrum (does economic growth drive investing, or do investors drive economic growth?) here, current capital flow trends suggest that any additional quantitative easing will also be felt primarily in emerging markets, rather than in the US. Not to mention that the US money supply has expanded at the same pace (or even slower) as the US economy over the long-term.

While the point about QE being ineffective is well-taken, Hudson completely ignores the strong case to be made for investing in emerging markets. He dismissively refers to all such investing as “extractive, not productive,” without bothering to contemplate why investors have instinctively started to prefer emerging markets to industrialized markets. As I said, emerging market economies are individually and collectively more robust, with faster growth and lower-debt than their industrialized counterparts. Calling such investing predatory represents a lack of understanding of the forces behind it.

Hudson also overlooks the role that emerging markets play in this system. The fact that speculative capital continues to pour into emerging markets despite the 30% currency appreciation that has already taken place and the asset bubbles that may be forming in their financial markets suggests that their assets and currencies are still undervalued. That’s not to say that the markets are perfect (the financial crisis proved the contrary), but rather that speculators believe that there is still money to be made. On the other side of the table, those that exchange emerging market currency for Dollars (and Euros and Pounds and Yen) must necessarily accept the exchange rate they are offered. In other words, the exchange rate is reasonable because it is palatable to all parties.

You can argue that this system unfairly penalizes emerging market countries, whose economies are dependent on the export sector to drive growth. What this really proves, however, is that these economies actually have no comparative advantage in the production and export of whatever goods they happen to be producing and exporting. If they can offer more than low costs and loose laws, then their export sectors will thrive in spite of currency appreciation. Look at Germany and Japan: both economies have recorded near-continuous trade surpluses for many decades in spite of the rising Euro and Yen.

The problem is that everyone benefits (in the short term) from the fundamental misalignments in currency markets. Traders like to mock purchasing power parity, but over the long-term, this is what drives exchange rates. Adjusting for taxes, laws, and other peculiarities which distinguish one economy from another, prices in countries at comparable stages of development should converge over the long-term. You can see from The Economist’s Big Mac Index that this is largely the case. As emerging market economies develop, their prices will gradually rise both absolutely (due to inflation) and relatively (when measured against other currencies).

Ultimately, the global economy (of which currency markets and exchange rates represent only one part) always operates in equilibrium. The US imports goods from China, which sterilizes the inflows in order to avoid RMB appreciation by building up a stash of US Dollars, and holding them in US Treasury Bonds. Of course, everything would be easier if China allowed the RMB to appreciate AND the US government stopped running budget deficits, but neither side is willing to make such a change. In reality, the two will probably happen simultaneously: China will gradually let the RMB rise, which will cause US interest rates to rise, which will make it more expensive and less palatable to add $1 Trillion to the National Debt every year, and will simultaneously make it more attractive to produce in the US.

Until then, politicians from every country and hack economists with their napkin drawings will continue to whine about injustice and impending economic doom.

Have you ever heard currency cheerleaders rave about how unique forex is because there is never a bear market? Since all currencies trade relative to each other (when one falls, another must necessarily rise), it couldn’t be possible for the entire market to drop at once, as happens with other financial markets. The ongoing currency war might be turning this logic on its head, as currencies embark on a collective downward spiral. Profiting in this kind of market might involve exiting it altogether, and turning to Gold.

For those of you who haven’t been following this story, a handful of the world’s largest Central Banks are now battling with each to see who can devalue their currency the fastest. [Of course, this war is being couched in euphemistic terms, but make no mistake: it is indeed a form of battle]. The principal participants are emerging market economies, which worry about the impact of rising currencies on their export sectors. However, industrialized countries have also intervened directly (namely Japan) and indirectly (US, UK).

Among the major currencies, there are only a few that continue to sit on the side-lines, including the Euro (to a certain extent), Canadian Dollar, and Australian Dollar. For as long as the currency war continues, these currencies and the handful of emerging market currencies that have forsworn intervention will be the winners (at least from the point of view of speculators that deliberately bet on them).

Then there are those that believe all currencies will suffer, and that even the currencies that are still rising are actually depreciating in real terms (due to inflation). Those who harbor such beliefs will often try to short the entire currency market, usually by betting on commodities or heavy metals, of which Gold is probably the most prominent.

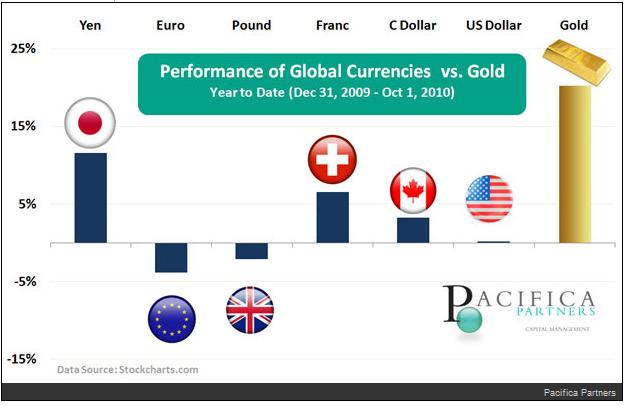

The price of Gold has risen more than 20% this year (in USD terms). Its backers claim that it is the ultimate store of value (where this derives from is unclear), and defend its lack of utility and inability to accrue interest by arguing that its appreciation is more than enough of a reason to own it. When you look at the performance of gold over the last five years, you begin to wonder if maybe they have a point.

Interest in Gold as an investment has surged in the last couple years (and especially the last few months), as the currency wars have heated up and the Federal Reserve Bank contemplates an expansion of its Quantitative Easing program (dubbed” QE2″). On the one hand, the notion that the only way to defend against real currency devaluation is to own “alternative” currencies is well-founded. On the other hand, regardless of the fact that the Fed has already minted $2 Trillion in cash and that the US national debt is expanding by $1 Trillion per year, inflation in the US is low. In fact, it’s at a 50-year low, and at an annualized .9%, it’s practically non-existent. You would think that with Gold’s unending appreciation, we would be in the midst of hyperinflation, but that’s simply not the case.

In the short-term, then, there’s really not a strong fundamental basis for investing in gold. That’s not to say that it won’t continue to appreciate and that investors will continue to buy into it merely to benefit from what has become self-fulfilling appreciation. From where I’m sitting, though, there’s really no foundation for this appreciation. Consider, for example, that gold investors still have to convert their gold back into paper currency in order for it to to be “used;” otherwise, it offers no benefit to the owner except that it looks pretty (though most investors wouldn’t know, since they buy gold indirectly). Not to mention that if/when the Dollar stops depreciating, there really isn’t really a justification to buy gold as a short-term store of value.

Over the long-term, the picture is certainly more nuanced. I’m not going to explore the viability of fiat currencies here, but suffice it to say that, “Positioning for significantly higher gold prices over the long run demands a very bold strategic bet: that the global monetary system as we know it will completely break down and be replaced with a gold standard.” Regardless of the merits of this point of view, those that invest in Gold should at least understand that this is really the only justifiable reason to hold it. Those who are buying it because of the ongoing currency war will be disappointed.

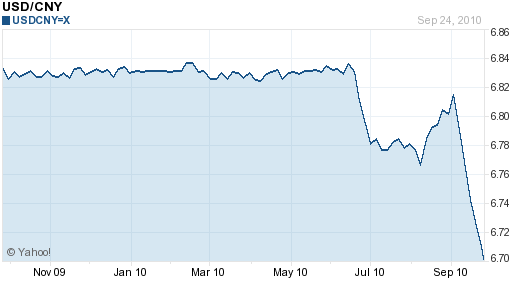

The Chinese Yuan has touched a new high, at 6.69 USD/CNY. Given that the Yuan has still only risen about 2% since the peg was officially loosened in June – with most of that appreciation taking place in the last couple weeks – there still remains intense pressure on China to do more.

Last week’s intervention by the Bank of Japan diverted a tremendous amount of attention towards the Yuan. In fact, many analysts have argued that it is only because of the Yuan-Dollar peg (itself, as well as the Chinese purchases of Yen assets that it engendered) that Japan was forced to act: ” ‘Countries see that getting involved in currency manipulation is a way to give themselves an advantage’…’China, their actions affected Japan, and Japan is affecting us.’ ” The Yen intervention could also force the G20 to re-focus its attention on the Yuan, and at least devote some discussion to it at the next summit.

It should be noted that the two soundbites above both emanated from US Congressmen, which is important because the US government is currently mulling action on the Yuan currency peg. Politicians are growing tired by the Treasury Department’s repeated failure to call China a “Currency Manipulator,” which would require diplomatic talks and even trade sanctions. The Treasury will have an opportunity redeem itself in its next report on foreign exchange, due out on October 15, but it is expected that the report will either be delayed or released without adequately addressing the undervalued Yuan.

In fact, Treasury Secretary Geithner testified before Congress last week, and at least admitted that something needed to be done: “The pace of appreciation has been too slow and the extent of appreciation too limited. We have to figure out ways to change behavior.” However, this was only in response to acerbic criticism – (Senator Schumer told him, “I’m increasingly coming to the view that the only person in this room who believes China is not manipulating its currency is you.”) – and he ultimately failed to outline a timetable/blueprint for action. Despite the consensus among politicians (and President Obama) that the currency peg is harmful to the US economy, Geithner made it clear that the Treasury Department continues to favor unilateral action towards dealing with problem, without Congressional intervention. For now, then, politicians are probably relegated to saber-rattling and name-calling.

China’s response to this charade has been predictable. Trade representatives hinted that China wouldn’t bow to external pressure, and that any attempt at “punishment” would be met with countervailing actions. China also questioned the economics between arguments that the Dollar peg contributes to trade imbalance, calling such claims “groundless.” This position is actually supported by the notion that while the Yuan appreciated by 20% against the Dollar from 2005-2008, the US/China trade deficit actually widened.

In practice, China is likely to stick to its policy of gradual Yuan appreciation, or a few reasons. First of all, while Chinese policymakers know that they don’t need to wholly appease US politicians, they at least need to pretend that they are listening. It’s true that the US is dependent on Chinese products and its purchases of Treasury Bonds. However, it is arguably just as dependent on the US to buy its exports, which promotes employment and social stability, and it is keen to avoid a trade war if possible.

Second, a long-term appreciation of the RMB is actually in China’s best interest. If it wants to spur domestic consumption and promote more value-added manufacturing, it will need a more valuable currency. Outbound M&A, especially involving natural resource companies, will also be more economical if the Yuan is worth more. Also, if China has any serious ambitions of turning the Yuan into a global reserve currency, it will need to create capital markets that are deeper and more liquid, which it is currently unmotivated to do, lest it spur demand for Yuan by foreign institutional investors.

Finally, China should let the Yuan appreciate because it is financially gainful to do so. As I mentioned above, its trade surplus with the US has widened over the last few years as prices for its exports grow along with quantity. Meanwhile, prices for imports and prices paid for commodities and other natural resources have declined in Yuan-terms. For that reason, I think China will probably continue to stick its current policy, and allow the RMB to continue to slowly inch up.

It was only last week that I mused about “Further Delays in RMB Revaluation.” Lo and behold, over the weekend, the Central Bank finally budged, by pledging to the members of the G20 that it would ” ‘proceed further with reform‘ of the exchange rate and ‘enhance’ flexibility.” Upon reading this, I suppose I should have felt stupid.

Still, I wondered whether the move was aimed as a political sop designed to appease Western countries, rather than a meaningful change in China’s forex policy. My suspicions were confirmed on Monday, when the markets opened, and the RMB jumped by a pathetic .4%. All of those who had been hoping for an expecting an instant revaluation a la the 5% jump in 2005 were sadly disappointed.

Most commentators shared my cynicism about the move. According to Goldman Sachs Group Chief Global Economist Jim O’Neill, ” ‘It’s pretty astute timing. The timing of it is clearly aimed at the G-20 meeting, which indirectly links to the whole renewed thrust in Congress with protectionist steps against China.’ ” If this was in fact China’s intention, it backfired, since it only succeeding only in bringing increased attention to the still-undervalued Yuan. Senator Sherrod Brown called the appreciation ” ‘a drop in a huge bucket….We’ve seen China take actions like this before when the spotlight is on, and then revert back to old tricks.” Thus, he and Senator Charles Schumer have announced that they will move forward with a bill to punish China, unless the RMB is allowed to significantly appreciate.

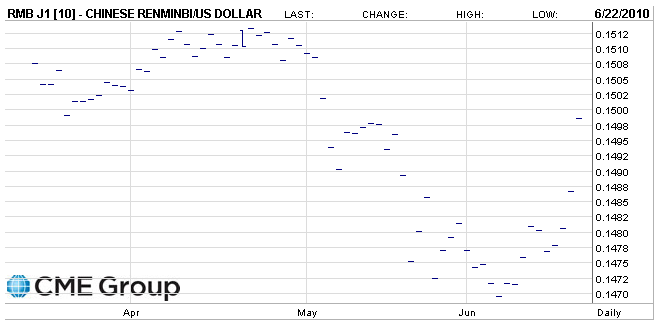

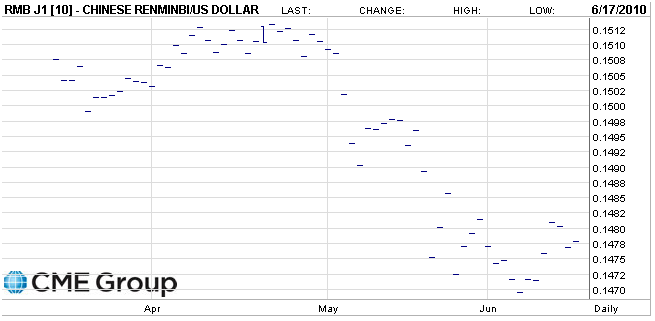

By the Central Bank of China’s own admission, this is unlikely. Instead, it will continue to “keep the renminbi exchange rate at a reasonable and balanced level of basic stability.” In other words, the RMB is still pegged squarely to the US Dollar. It is neither freely floating nor is it pegged to a basket of currencies (in which case it could conceivably appreciate faster against the Dollar, due to the weak Euro). It is technically allowed to rise and fall on a daily basis within a .5% ban, but even this is controlled tightly by the Central Bank, via the so-called Central Parity Rate. If the rate fluctuates too much, state-owned companies often intervene in the markets at the behest of the Central Bank. Legitimate market participants are heavily constrained by a rule that requires them to square all of their positions at the end of every trading session, such that making long-term bets on the RMB’s appreciation would be impossible.

Not that it matters. In the US, where it is legal to make long-term bets on the RMB (via futures contracts), investors are still only projecting a 1.8% appreciation (2.2% relative to the RMB’s pre-revaluation level) over the next year, and a 2.9% appreciation by the end of 2011. In the end, there just isn’t a lot of confidence that China will voluntarily act in a way that is contrary to its own short-term economic interests.

To be sure, there is a possibility that the RMB will be allowed to steadily appreciate, in which case there would be real implications for other financial markets. If the past is any consideration, however, the RMB will rise only modestly against the Dollar, and even more modestly on a trade-weighted basis. Its economy will remain overheated and imbalanced, and if it was headed towards collapse prior to this latest change, it certainly still is.

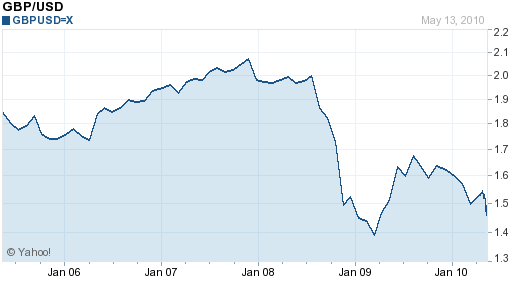

Compared to the Euro, the Pound is Gold (figuratively speaking). Compared to everything else, well, the Pound is probably closer to linoleum. Bad geology metaphors notwithstanding, there really isn’t much to get excited about when looking at the Pound.

Let’s take the election, for example. Originally billed as a chance for a fresh start, politically, for the UK, the election has turned out to be nothing short of disastrous. Rather than producing a clear-cut victory, it has resulted in a hung Parliament. The way talks are currently shaping up, it looks like power will be shared by the Liberal Democrats and Conservatives. This is problematic,because neither party has a clear vision for dealing with the skyrocketing UK national debt; with the two parties working together, meanwhile, a compromise seems even more unlikely. “Investors are worried that a hung parliament will result in a weak government that will be unable to force through measures to reduce the UK’s high borrowing levels.”

As a result, many analysts now believe that the UK could lose its coveted AAA credit rating: “We believe that a downgrade…is more than likely since both parties agree that early expenditure cuts could harm the economy. The alternative could be that both parties agree on tax hikes to be implemented with the next budget. Both outcomes would be equally bearish for sterling.’ ”

Even aside from the imminent UK fiscal crisis, there is the fact that its economy continues to stagnate, its capital markets remain languid, and its balance of trade remains perennially mired in deficit. “Figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) showed that gap between the UK’s imports and exports hit a massive £7.5bn in March. The deficit — well ahead of an upwardly revised £6.3bn for |February — came as total imports surged £1.4bn over the month compared with a meagre £200m rise in exports.” From a fundamental standpoint, then, there is very little reason to own the Pound.

The picture is slightly more nuanced, when viewed through the lens of technical analysis. The most recent Commitment of Traders report, meanwhile, has showed short interest in the Pound building to record levels. In addition, the ratio of long/short positions is approaching 5:1. Some analysts believe this is inherently unsustainable, and that as net positions become more lopsided, a sharp reversal becomes even more likely. Then again, some analysts had the same theory about the Euro, which was solidly disproved after the short-squeeze rally was soon followed by a steady decline and a re-accumulation of short positions.

Other technical analysts are waiting to see where the Pound moves in the near-term before placing their bets. ” ‘Last week the market eroded the 15-month uptrend from the January 2009 low at $1.3500’…the $1.4255 Fibonacci level is the last defence for the pound ahead of the $1.3500 2009 low. For the downside pressure to be taken off, key resistance at $1.5055, the May 10 high, would need to break.’ ” The Pound is hovering dangerously close to a number of psychologically important levels. If it breaches $1.40, it would signal a 5-year low. Consider also that the Pound last touched $1.38 in 2001 and $1.35 in 1987.

To be fair, the Pound has hovered around $1.50 for most of the last 20 years, so its current level against the Dollar is not that low, relatively speaking. If investors come to their senses, and realize that the likelihood of UK sovereign default is probably not any higher than the US, and the coalition government is able to produce a convincing plan for reducing the deficit, then the Pound could bounce back. If the safe-haven mentality remains in force, however, the Pound will continue to be one of the big losers.

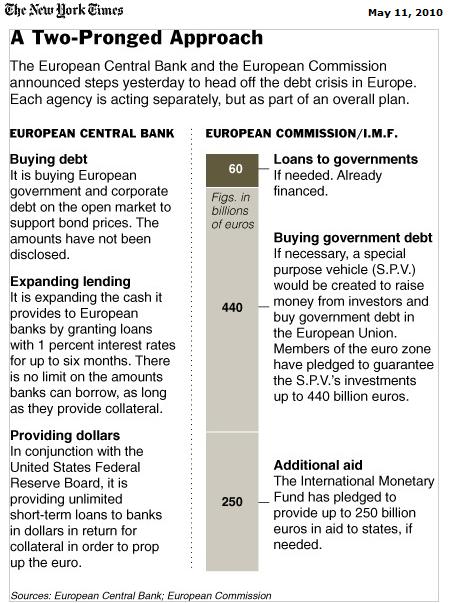

In my last post, I reported that the markets were incredibly bearish on the Euro, due to concerns that the Greek debt crisis could neither be mitigated nor contained. By following up on this report with another incantation of Euro bearishness, I certainly run the risk of belaboring the point. Still, the fact that since then, a $1 Trillion bailout was announced means that at the very least, I need to offer an update!

Anyway, in case you have been living in a cave, the EU finally put its money where its mouth was by forming a €750 Billion Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) to address the fiscal problems of currently-ailing and potentially-ailing economies. The brunt of financing the SPV will fall on individual Eurozone countries, though the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) will also make sizable contributions. In addition, the European Central Bank (ECB) has agreed to purchase an indeterminate amount of government and corporate bonds, while other Central Banks will use currency swaps to ease pressure on the Euro.

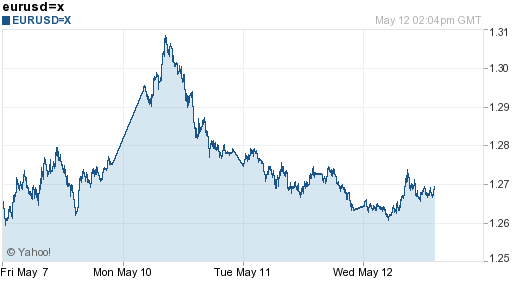

The reaction to the news was quite positive, with the Euro reversing its 6-month slump and rallying 2.7% against the Dollar. Equity shares surged on the news: “A a 50-stock mix of European stocks jumped 10.4 percent, Spain’s market soared 14.4 percent, France’s rose 9.7 percent and Germany’s gained 5.3 percent.” Sovereign debt and credit default swap prices also rose as investors moved to price in a decreased likelihood of default.

The celebration was short-lived, and by Tuesday (yesterday), the Euro had already returned to its pre-bailout level against the Dollar. In hindsight, it looks like the rally was the result of a classic short-squeeze. On Sunday, the Financial Times reported that “Positioning data from the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, often used as a proxy for hedge fund activity, showed speculato,rs increased their short positions in the euro to a record 103,400 contracts, or $16.8bn in the week ending May 4.” After the most exposed short positions were covered, however, the rally quickly came to an end: “By the time markets opened in the United States, and American hedge funds entered the market, the euro’s rally began to flag.”

Indeed, it’s hard to find anyone that has anything positive to say about the bailout, even among the bureaucrats and politicians that contrived it. Here’s a smattering of soundbites:

There are a few specific concerns about the bailout. First of all, it’s still unclear how it will be paid for and how it will be implemented. How will specific loans be issued, and what will be the accompanying terms? Second, it does nothing to address the underlying fiscal problems that precipitated the crisis, and may in fact exacerbate them since countries have less of an incentive to rein in spending. As one analyst summarized, “Bailing out economies creates moral hazard. Other countries may continue to skirt the kinds of actions that would lower their budget deficits and debt loads…because they too can expect to be rescued.” Finally, the bailout does nothing to mitigate credit risk for private lenders; it merely transfers and expands it, since money that would have been lent to Greece (and other problem countries) anyway, will still be lent to them, after first being funneled through the SPV. In short, “Once market participants look at the actual details of this plan, they are not going to want to buy the euro either.”

As everyone has been quick to point out, the bailout probably makes a (partial) dissolution of the Euro even more likely, because it is tantamount to deflating the currency. As one economist opined, “The euro zone does not look viable in its current form. The basic premise…to unify monetary policy….while keeping fiscal policy completely separate…has completely broken down.” The only solution which will leave the Euro intact is for the weakest members to leave, and for a solid core of economically and fiscally sound economies to remain behind.

To be fair, the EU has certainly bought itself some time. Given that the amount of money pledged to fight the debt crisis well exceeds Greece’s public debt, it won’t be Greece that brings down the Euro. If/when the debt problems of Spain, Portugal, and Ireland become insoluble, however, the futility of the bailout will become abundantly clear.

Forget about Greece: What about the US, Japan, and the UK? Almost 75% of trading in the forex markets involves some combination of the US Dollar, Euro, Japanese Yen, and British Pound. This figure rises to more than 95% when you include trading in which at least one of the currencies (as opposed to both) is one of the aforementioned. In short, these four currencies are by far the most important in forex markets, and most patterns/narratives in forex markets tend to involve them.

It’s simple supply and demand, really. These currencies are the most heavily traded because their economies are the largest and their capital markets are the deepest and most liquid. [The absence of the Chinese Yuan from this list can be explained by the lack of flexibility in its capital controls and exchange rate regime]. When investors flee one of these major currencies, they tend towards one of the others, and vice versa.

This phenomenon has especial relevance in the realm of sovereign debt. While some investors would love no more than to move their capital from the four debt-ridden currencies above, there just isn’t enough supply of alternative currencies to absorb the outflow. The Swiss Franc, Australian Dollar, and Canadian Dollar (#5, 6, & 7 on the list of most traded currencies), for example, have all surged over the last year as investors have looked for stable and liquid alternatives to what can be dubbed the Big-4 currencies. While these currencies still have some room for appreciation, they can’t continue to rise forever. For better or worse, then, the most useful comparison when it comes to to sovereign debt is not between the Big-4 and everything else (aka the major currencies and the emerging market currencies), but rather between the Big-4 themselves.

Forgive me for this long-winded introduction, but I think it’s important to understand the usefulness of comparing Japan with the US with the EU with the UK when all of these economies have terrible fiscal problems, and why we can’t just compare them to fiscally sound economies. With that being said, let the comparison commence!

Most of the fallout from the sovereign debt crisis has affected the EU and the Euro. This is for good reason, since the focal point of the crisis is a member of the Euro (Greece), and several other Eurozone countries are on the periphery. I addressed the EU in a previous post (EU Debt Crisis: Perception is Reality), so I think it makes sense to focus on the others here.

In terms of debt sustainability, the UK is not far behind Greece. “The flood of British debt is likely to ‘lead to inflationary conditions and a depreciating currency,’ lowering the return on bonds. ‘If that view becomes consensus, then at some point the UK may fail to attain escape velocity from its debt trap,’ ” explained one analyst. With high budget deficits projected for at least the next five years, the Bank of England no longer buying UK bonds, and the possibility that the ucoming elections could produce political stalemate, the fiscal position of the UK can only deteriorate. On the plus side, the average maturity for UK bonds is 13.7 years, twice the OECD average, which means that it could be more than a decade, before Britain really begins to feel the squeeze.

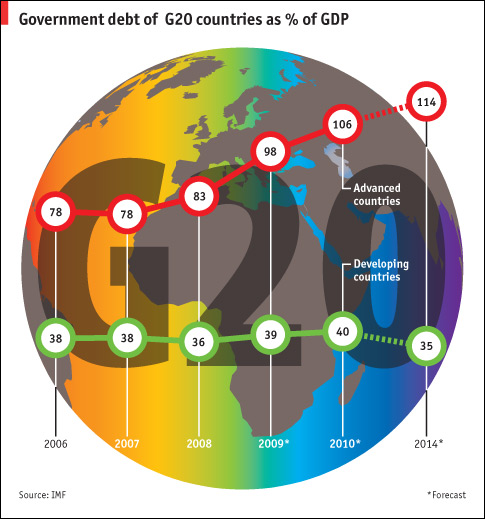

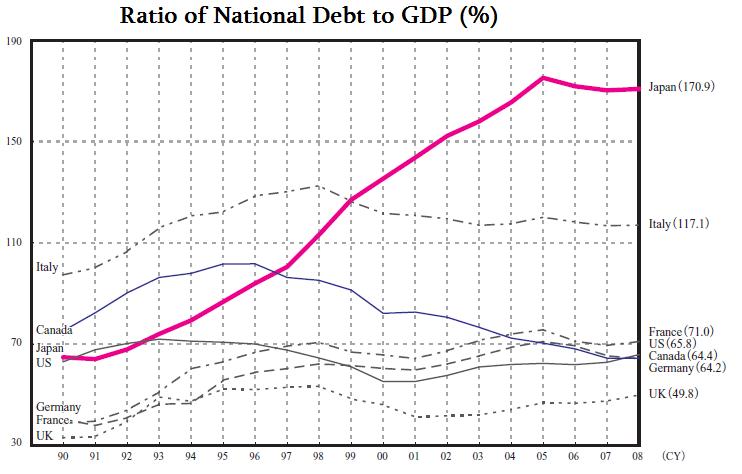

Japan might not be so lucky. Its net debt already exceeds 100% of GDP and its gross debt is approximately 200% of GDP; both are the highest in the OECD. Meanwhile, the average maturity of its debt is only five years, so there isn’t a lot of time to act. According to analysts, the crisis would most likely assume the following form: “ ‘A surge in yields would lead to a combination of extreme fiscal contraction, through tax increases and welfare cuts’…as well as to even more monetary expansion, perhaps less central bank independence and ‘presumably a much weaker exchange rate.’ ” In the case of Japan, the mitigating factor is that 90% of government debt is held domestically. Therefore, Japan isn’t vulnerable to the whims of foreign creditors, and an outright default is unlikely.

Then, there is the US. Its Trillion Dollar budget deficits, and multi-Trillion Dollar national debt and entitlement obligations are the highest in the world in nominal terms. On the other hand, the US government has not really encountered any difficulty in financing its spending. Political opposition is fierce, but investors have lined up to buy Treasury bonds and record low yields. This will likely change as the Fed curtails its purchases, and the economic recovery gives rise to higher interest rates. Analysts expect that borrowing costs (i.e. Treasury yields) could rise more than 1.5% by the end of 2010.

From the standpoint of markets, its impossible to say which economy’s fiscal problems are the most serious, since sovereign debt yields have declined across-the-board over the last 20 years. One Professor of Finance explains this trend as follows: “Behavioral factors keep many bond traders and investors from recognizing the reality of the situation…since there is no well-defined crisis point.” In other words, the crisis in Greece is only a test run. The real one could come in a few years, and involve a much larger economy. At that point, currency traders will have to decide who to back.

One of the pitfalls of forex blogging (or all financial reporting for that matter) is that it’s inherently after-the fact. In other words, any information about the past – while relevant – is inherently useless, since it has theoretically already been priced into the asset (or currency in this case). Before I begin my post on the Pound’s recent decline and the factors that wrought it, then, I wanted to offer the caveat that in analyzing past events, we must simultaneously look to the future.

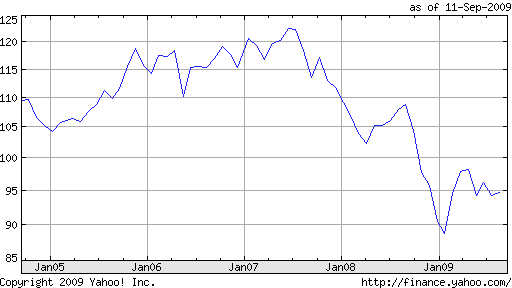

Anyway, for anyone watching the Pound Sterling over the last month, its performance has been startling. It is down 7.5% for the year already (we’re only in March!), and has fallen 12% from its August peak of 1.70 USD/GBP. This represents an unbelievable about-face, as the Pound spent much of 2009 floating upwards following its lows from the credit crisis.

What’s behind the decline? In short, economics and politics, or more precisely, the junction of economics and politics. As the British economy began its recovery from recession, analysts began to turn their attention to UK government finances. Another way of looking at this would be to say that analysts have shifted their gaze from the positive effect of government intervention (i.e. economic recovery) to the many lasting negative effects. Inflation and government solvency, of course, are the two most pernicious of the bunch.

The Bank of England’s quantitative easing program was comparable to the Fed’s program in relative terms, and in the aftermath of all of that money creation, inflation is slowly creeping up. The government’s free spending also contributed, and now, so is the sinking Pound, as prices for commodities and other imports are rising fast in local currency terms. Speaking of government spending, the UK government budget deficit is projected at 12% for 2010, slightly higher than 2009. You can see from the chart below that budget deficits are forecast to remain large for the next few years. Expectations are so low, in fact, that a reduction in the deficit to 3% of GDP by 2014-2015 would be viewed as a victory.

Naturally, the UK government feels some pressure to reduce its deficit, both for the sake of financial solvency and to control inflation. The problem is that an election must be called before June, and until then, there is natural pressure to continue operating the money printing presses 24/7 in order to appease the voting public. The same goes for the Bank of England; it can’t be expected to tighten monetary policy and/or reverse quantitative easing until after the election.

I’m not going to pretend that I understand British politics, but from what I’m hearing, it seems the problem is that the election polls are now very close. Previously, a major victory by the Conservative Party was seen as inevitable, and this was viewed positively by financial markets because of the expectation that they would rein in spending. Recently, the incumbent Labour Party has closed the gap, to the extent that a hung Parliament is now a likely outcome. This would be even less desirable than an outright Labour victory, because the sharing of power would make it unlikely that reforms of any kind would be enacted. With regard to forex, some have posited an inverse correlation between the rising popularity of Labour and the falling Pound.

With the crisis in Greece still unresolved, analysts are also making comparisons to the UK. Some have suggested that if Greece were to receive a bailout, then, investors would turn their attention to the UK, whose finances are in equally bad shape. Without the protection of the Euro, the Pound would be open to speculative attack. On the other hand, that the (declining) Pound is independent from the Euro could become in advantage, if it boosts exports.

Going forward, it’s difficult to make any predictions until after the elections and/or the government makes a firm commitment to reduce spending and lower its deficit. Some analysts think that regardless, the Pound is doomed to continue falling, perhaps all the way to the $1.40 mark. Others see the current decline as the “darkness before the dawn.” As I noted in the introduction to this post, the latter could certainly be right. Besides, most of the uncertainty has probably already priced in. While most of the factors currently weighing on the Pound are bearish, some contrarian investors might see this as a good opportunity to buy. And who’s to say they’re wrong?

With this post, I want to try to clarify the Greek fiscal crisis. The problem is that it’s not clear exactly how serious the problem is, because most of the media coverage of the crisis has been directed towards the financial markets’ perception of it, rather than its underlying fundamentals. In the end, I think it’s important to understand both.

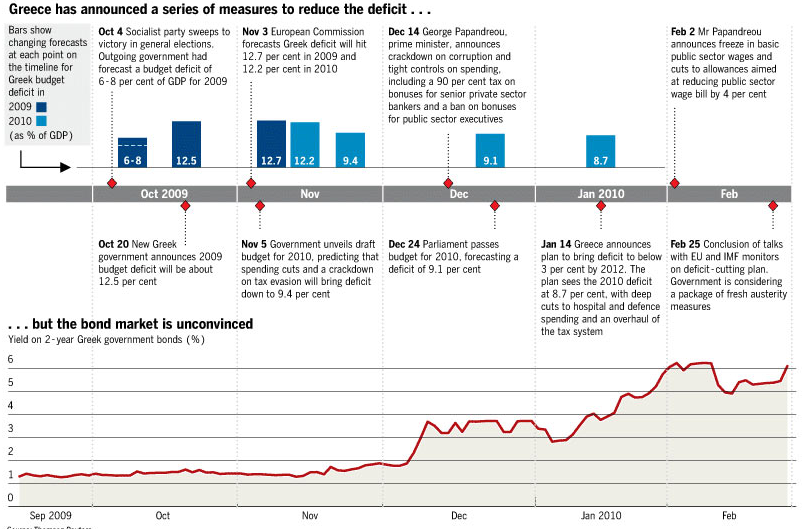

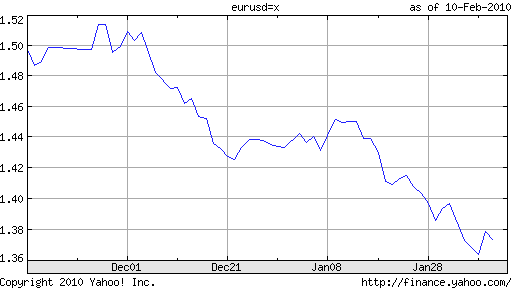

The Financial Times published a great timeline that shows perception and reality side-by-side. While there were certainly other important developments that bear in Greece’s fiscal position (in addition to those listed below), you can see that financial markets are basically making their own reality. For example, there was hardly a response to the October announcement that Greece’s budget deficit would be 12.7%, which was 5% higher than earlier estimates. In fact, the markets only became bearish on Greek debt after it the government announced that it would try to bring the debt down to 9.4% through various measures.

Apologists for the markets would be right to wonder why investors should be inclined to believe the government of Greece when it said it could control the budget deficit. Fair enough. Still, one has to wonder why the markets suddenly started worrying about Greece’s fiscal problems, when only a couple months ago, the possibility of a whopping 12.7% budget deficit barely caused investors to blink. Besides, the credit crisis has been raging since 2008, which means the markets have had plenty of time to digest the implications of recession for Greece’s fiscal position.

These days, where is a financial crisis, chances are derivatives are not far removed. As credit default swap spreads (i.e. the cost of insuring against default by Greece on its loan obligations) have risen, so have concerns that this is a bona fide crisis. “It’s like the tail wagging the dog…There is a knock-on effect, as underlying positions begin to seem riskier, triggering risk models and forcing portfolio managers to sell Greek bonds,” said one portfolio manager. From this perspective, it almost looks like this “crisis” is being completely manufactured by speculators for the sake of profit. Summarized another analyst, “It’s like buying fire insurance on your neighbor’s house — you create an incentive to burn down the house.”

To be fair, Greece also played a role in derivatives speculation, and on some level, it was even more nefarious than the speculators. Assisted by Goldman Sachs (who is now betting on Greek default [how un-ironic that is!]), Greece entered into a series of swap agreements last decade, which it used to conceal its true debt burden. “By using an historical exchange rate that didn’t accurately denote the market value of the euro, Goldman effectively advanced Greece a €2.8 billion loan. Under EU accounting rules—which were tightened in 2008—Greece wasn’t obliged to include the loan in overall public debt on its books.” Now that those transactions have been uncovered and the truth is coming to light, financial markets are rightly re-evaluating the risk of further lending to Greece.

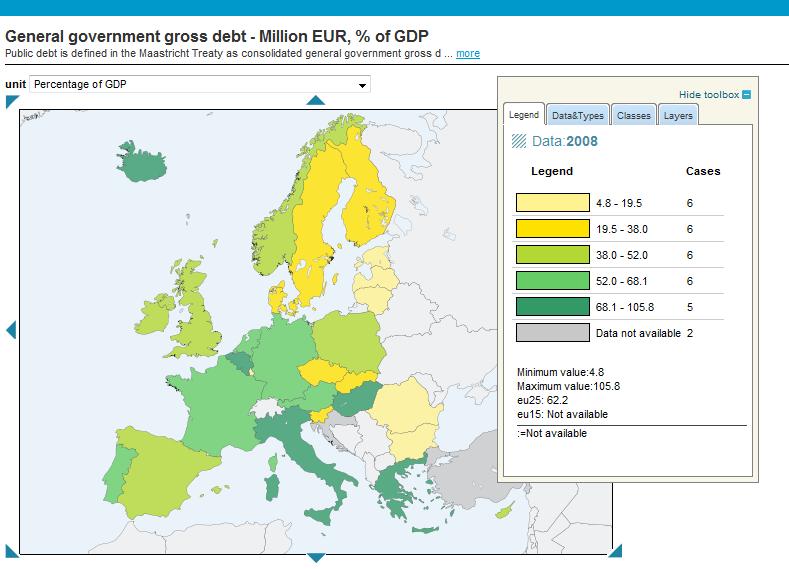

There is no question that Greece’s debt problems are serious. As to whether labeling it a crisis is necessary, that depends on your standards. Greece ranks near the top of the list on a variety of individual “debt sustainability” criteria. At 94.6% of GDP, it’s net debt is among the highest in the world. Its projected 2010 budget deficit is also high, though not the highest. Its cost of borrowing is also significantly higher than projected GDP growth, which means that net debt will continue to grow until a budget surplus can be produced. When you average these measures together, it appears that Greece’s debt problems are the most unsustainable of any country in the world. But this is hardly news.

On the other hand, the weighted average of the maturity of Greek debt is 7.7 years, well above average, and plenty of time (relatively) for Greek to sort through this mess and secure new lenders. Towards the latter end, it has hired a former bond trader to head its debt management agency. In order to improve its fiscal position, it has announced a series of austerity measures, including budget cuts, tax increases, wage cuts for public-sector employees, and stricter laws against tax evasion.

At this point, a ratings downgrade looks inevitable, and some analysts think the crisis has already become self-fulfilling. As borrowing costs rise, it only makes it more likely that Greek will default, which causes rates to rise further, and so on. On the other hand, Greek politicians are being forthright about their position (“Greece’s finance minister, George Papaconstantinou, remarked this week: ‘People think we are in a terrible mess. And we are.’ “) and have a plan for rectifying the situation. There is cause for skepticism here, but also for hope. And that goes not just for Greece, but also for the Euro.

Currency markets operate in funny ways. Greece’s fiscal problems are hardly a new development. During years of boom and bust alike, it ran unsustainable budget deficits. Why investors have decided to fret now – as opposed to last year or next year, for example – on the distant possibility of default, is somewhat mysterious.

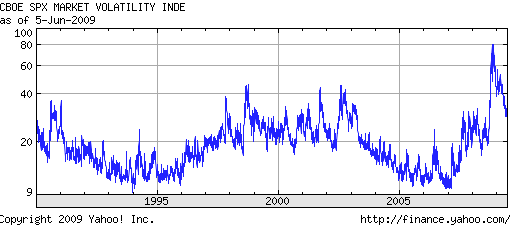

After all, the credit crisis exploded in 2008, and conditions now are inarguably more stable than they were at this time last year, when volatility and credit default spreads (insurance against bond default) – two of the best measures of investor risk sensitivity – were still hovering around record highs. On the other hand, the unveiling of Dubai’s hidden debt problems, has certainly provided impetus to investors to re-evaluate the fiscal situations in other highly leveraged economies. In addition, Greece just estimated that its budget deficit for 2010 at 12.7%, 4% higher than earlier estimates, which were also shockingly high. Regardless of 1, the markets are now focused firmly on Greece – and by extension, the Euro.

How serious are Greece’s fiscal problems? Serious, but not insurmountable. Its sovereign debt recently surpassed 125% of GDP, higher than the US, but lower than Japan, for the sake of comparison. Of course, the Greek economy is hardly a picture of robustness. Neither is the US, these days, for that matter, but its size means that it is pretty much immune from speculative attacks on its credit and capital markets. Greece, on the other hand, remains extremely vulnerable to the whims of international investors.

On the whole, these investors still remain willing to finance Greece’s budget deficits; the last bond issue was five times oversubscribed, which means that demand exceeded supply by a healthy margin. Still, interest rates are rising quickly, and spreads on credit default spreads have risen above 400 basis points, suggesting that nervousness is growing and Greece cannot take for granted that future bond issues will be met with such healthy demand.

In this context, in stepped the European Union. In fact, it isn’t even clear if Greece asked for help. As I pointed out above, the Greek debt “crisis” is largely playing out in capital markets, and doesn’t necessarily reflect a change in the fiscal reality of Greece. Still, leaders of the EU were alarmed enough to convene a meeting between the finance ministers of member states, to discuss their options.

After weeks of denial that any kind of aid to Greece was being considered, EU political leaders announced that they were prepared to step in to help after all, but they were vague on the details. There were no ledges of specifc dollar amounts, only hazy promises of support should conditions warrant it. In the end, what was clearly intended to comfort the markets achieved the opposite effect, as investors took no comfort in the “moral support” and worried about the new uncertainty.

It’s premature to say whether this whole episode will threaten the viability of the Euro. Much depends on whether Greece (Portugal and Spain, too, for that matter) can get its fiscal house in order (Among other things, it has promised to reduce its 2010 budget deficit by 4%). More importantly, it depends how, and to what extent, the EU responds to this crisis as a community. The Euro is already 10 years old, and you would think that it would have been accepted already within the EU, as it has by the rest of the world. On the contrary, it remains deeply divisive and fraught with politics. Many of its critics have seized on this opportunity to challenge to raise fresh calls for its abolishment. If the problems of Greece deteriorate to the point that other EU members are actually required to intervene, you can expect these calls to crescendo.

Last month, I reported on how anticipation is (was) building towards a revaluation of the Chinese Yuan (RMB), confidently stating that “The only questions are when, how and to what extent.” While I’m not ready to recant that prediction just yet, I may have to temper it somewhat.

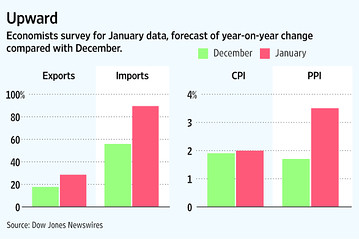

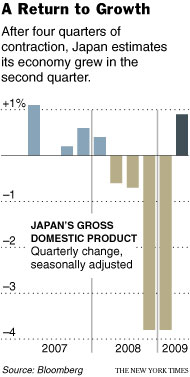

On the one hand, the case for RMB revaluation is stronger than ever. Among large economies, China’s economy is by far the strongest in the world, clocking in GDP of close to 2009% while most other economies were lucky to “break even.” Meanwhile, its export sector – supporting which is the primary purpose of the RMB peg – is once again robust, having recovered almost completely from a drop-off in demand in 2008 and the first half of 2009. In fact, exports grew by 30% in January, on a year-over-year basis. China’s share of global exports is now an impressive 9%, up from only 7% in 2006. From an economic standpoint, then, the case for an artificially cheap currency is no longer easy to make.

At the same time, the RMB peg is contributing to bubbles in property and other asset markets. That’s because the Central Bank of China has been forced to mirror the monetary policy of the Fed, as a significant interest rate differential would stimulate uncontrollable capital inflows from yield-hungry investors. While the US can still handle interest rates of close to 0%, China’s economy clearly can not. Thus, consumer prices are slowly creeping up, and property prices are soaring. The most effective (and perhaps the only) way for China to contain both consumer price and asset price inflation is to hike interest rates, which which in turn, would necessitate a rise in the RMB.

There is also the notion that the peg is becoming increasingly costly to maintain. China’s forex reserves already total $2.4 Trillion, and each Dollar that it adds will be worth less if/when it ultimately allows the RMB to appreciate further. In addition, China’s economic policymakers continue to fret about its exposure to the fiscal problems of the US, with one pointing out that, “China has effectively been kidnapped by U.S. debt.” Of course, they no doubt realize that there isn’t a better option at this point; its attempt to diversify its reserves into other assets proved disastrous. The solution to both of these problems, of course, would simply be to allow the Yuan to fluctuate based on market forces, or at least for it to resume its upward path of appreciation.

Political pressure on China to revalue, meanwhile, is even stronger than it was last month. While not invoking China by name, President Obama has been increasingly blunt about the need to pressure it on the RMB: “One of the challenges that we’ve got to address internationally is currency rates and how they match up to make sure that our goods are not artificially inflated in price and their goods are artificially deflated in price.” In addition, rumor has it that the Treasury Department could finally label China as a “currency manipulator” in its next report, which would allow Congress to impose punitive trade sanctions.

Developing countries, which now account for a majority of China’s exports, are also increasingly unhappy with the status quo. The peg to the Dollar caused many emerging market currencies to appreciate rapidly against the Yuan in 2009, and there is evidence that many of their trade imbalances with China are rapidly worsening, “with exports to India, Brazil, Indonesia and Mexico growing by 30% to 50% in recent months.” As one analyst pointed out, however, the potential backlash from this development could be massive: “It’s one thing to produce job losses in the U.S., but it’s another to produce job losses in Pakistan,’ with which China has close military ties.”

On the other hand, however, is China’s massive reluctance to allow the Yuan to appreciate. Part of this is related to face; with the US and other countries stepping up pressure on a number of fronts, China’s leaders don’t want to be seen as weak, and could act contrary to their own interests if it thinks it can earn political points in the process. “China is unlikely to make significant concessions to U.S. pressure on the yuan, particularly now when the two countries are involved in a range of disputes, including U.S. arms sales to Taiwan,” explained one analyst. More importantly, the leadership is nervous that the nascent economic recovery is not sufficiently grounded for the peg to be loosened. While 9% growth in most other economies would be cause for celebration, in China, it is being interpreted as evidence of fragility.

There you have it. Reason on one side, and politics on the other. Unfortunately, it seems that politics always triumphs in the end. Despite Treasury Secretary Geithner’s recent assertions that the RMB will rise soon, investors know that China ultimately calls the shots: “When it comes to the exchange rate, China’s main consideration is China’s own stable economic growth and the structural adjustment of its economy. Foreign pressure is only a secondary consideration.” In short, the RMB is now projected to appreciate only 2% in 2010, according to currency futures, compared to 3.5% last month.

As if forex traders didn’t have enough to worry about these days, now there is a new concern- that of sovereign debt default. The last couple months have witnessed a spate of minor episodes, all of which paint a picture of frightening cohesiveness about the state of sovereign finances, and the ability of countries to continue to finance and service their debt. As the economic recession moves into recovery (or at least, permanently distances itself from the prospect of depression), the markets will likely turn their gaze towards the long-term, with this issue looming large.

It’s difficult to know where to begin, since people have been talking about the perennial budget deficits of the US for many years. As a result of the economic downturn (stimulus programs and falling tax revenues), these budget deficits have taken on truly awesome proportions. The 2009 deficit came in at a record $1.4 Trillion, and the deficit in the fiscal year-to-date 2010 is close to $300 Billion.

The US, of course is far from alone, with virtually every nation (industrialized and developing, alike) operating in the red. Canada, Britain, Japan…even China – known for its fiscal prudence – are setting records with their budget shortfalls.

As a result, “Moody’s…suggested that the countries’ triple-A ratings could face downgrades in coming years.” Greece’s sovereign debt was already downgraded, from AAA- to BBB+, while Spain has received a warning. Dubai is in technical default, but this is old news.

It’s not as if any of this is surprising, or even new. Greece, for example, was running 10% budget deficits during the height of the credit bubble. With the bursting of the bubble, however, sovereign fiscal problems have both been both exposed and exacerbated. If ever there was a time when national governments could be expected to get their fiscal houses in order, this is not it.

At this point, the markets appear to have resigned themselves to sky-high deficits for the immediate future, and have now begun to assess the implications rather than try to encourage governments to straighten out. Even though the US budget deficits and national debt are the highest in nominal terms, its Treasury bonds still remain the standard-bearer for global capital markets. Proving that point is that new Treasury issues are repeatedly oversubscribed, despite rock-bottom rates. “For every $1 of debt sold by the Treasury this year, investors put in bids for $2.59, up from $2.19 at this point in 2008.” Most importantly, the largest creditor – China – is headlining demand. Granted, the costs of insuring US debt (via credit default swaps) is rising, but investors generally remain cautiously optimistic about US finances.

The story on the other side of the Atlantic is not nearly as upbeat. Investors responded to the downgrade of Greece’s credit rating, by pushing up the yield on its debt by 50 basis points, raising the spread to 2.5% over comparable German sovereign bonds. Ireland, meanwhile, is projecting a budget deficit of 13.2% this year, and Austria is receiving scrutiny for its banks’ risky lending practices in Eastern Europe. “The question for Europe now is how much more solvent are countries like Italy, Portugal and Spain…Could it be that these are the regions where the next financial shoe is going to drop?” Asked one analyst.

The more important question is what would happen in the event of default, or even a spike in bond yields by a member of the EU. Technically, the treaty behind the European Monetary Union “contains a ‘no bail-out’ clause that prohibits one country from assuming the debts of another.” It seems hard to believe – from where I’m sitting at least – that other countries would sit by idly if one member began moving inexorably towards bankruptcy. Investors are certainly not blind to the notion of an implicit guarantee, which helps the weak at the expense of the whole. That could explain why Greek and Spanish bonds remain comparatively buoyant, while the Euro has suffered in recent sessions.

Then, there is the UK. Of all of the world’s major economies, the UK is arguably in the most precarious financial position, especially relative to its size. As one commentator lamented, “Indeed, the cost of our [UK] government borrowing – as measured by the interest rate – is rising so quickly that within a month it could be higher than Italy’s.” He goes on to discuss how inflating away the debt would be pointless, given the sophistication of investors and the fact that government liabilities are indexed to inflation, and hence would offset any gains from debt devaluation. He concludes: “The solution to today’s fiscal crisis is the same as it has always been: to cut spending, reduce the deficit and learn to live within our means.” Based on modern history, that seems pretty unlikely. Could Britain, then, become the first industrialized country to default on its debt? Forex markets: take note.

Then, there is the UK. Of all of the world’s major economies, the UK is arguably in the most precarious financial position, especially relative to its size. As one commentator lamented, “Indeed, the cost of our [UK] government borrowing – as measured by the interest rate – is rising so quickly that within a month it could be higher than Italy’s.” He goes on to discuss how inflating away the debt would be pointless, given the sophistication of investors and the fact that government liabilities are indexed to inflation, and hence would offset any gains from debt devaluation. He concludes: “The solution to today’s fiscal crisis is the same as it has always been: to cut spending, reduce the deficit and learn to live within our means.” Based on modern history, that seems pretty unlikely. Could Britain, then, become the first industrialized country to default on its debt? Forex markets: take note.

In my report on last month’s Japanese election, I noted that the newly-appointed Japanese finance minister, Hirohisa Fujii, had spoken out against forex intervention. With that, it seemed the matter was closed.

But not so fast! Over the following few weeks, Fujii (as well other members of the new administration) moved to clarify his position, backtracking, sidestepping, contradicting, but never going forward. The following is a summary of selected remarks, beginning with the original statement against intervention and ending in what seems like a promise to intervene:

September 15: “I basically believe that, in principle, it’s not right for the government to intervene in the free-market economy using its money, either in stock or foreign-exchange markets.”

September 27: [The Yen’s rise is] “not abnormal…in terms of trends.”

September 28: “That’s not to say I approve of the yen’s rise.”

September 28: “I don’t think it is proper for the government to intervene in the markets arbitrarily.”

September 29: “If the currency market moves abnormally, we may take necessary steps in the national interest.”

October 3: “As I have said in Tokyo, we will take appropriate steps if one-sided movements become excessive.”

October 5: “If currencies show some excessive moves in a biased direction, we will take action.”

Confused? I know I am. Is it possible to glean any semblance of meaning from these remarks? Summarized one columnist, “Hirohisa Fujii has gone through several cycles of remarks that first appeared to favor a strong yen and then seemed to backpedal after markets took him at his word and sent the Japanese currency soaring.”

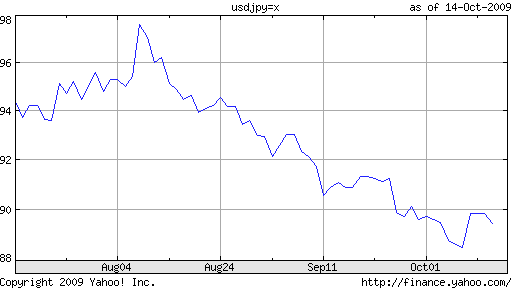

I think this encapsulates the regret that Minister Fujii must have felt, after his original comments were taken a little too seriously. In hindsight, it appears that Fujii attempted to convey the new administration’s stance on forex, in a nutshell, and certainly didn’t expect that investors would run wild and send the Yen up another 4%, bringing the year-to-date appreciation against the Dollar to 15%. In the words of the same columnist cited above, “Japan’s finance minister has been rudely reminded of the cardinal rule when speaking to markets — less is more.”

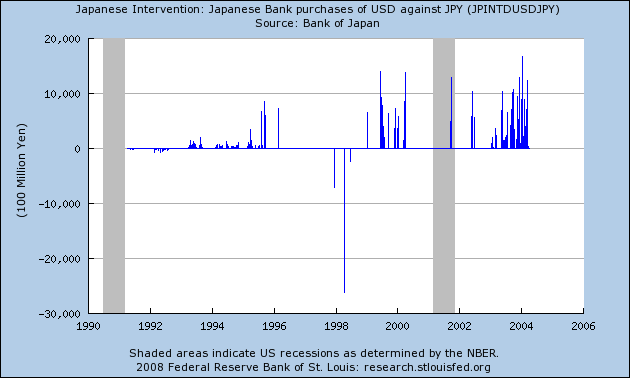

So where does Fujii actually stand? I would personally hazard to guess that his original explication is still the most accurate portrayal of how he will tend to the Yen while in office. The former Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) administration intervened several times while in office (once under the direction of Fujii himself!) and most recently in 1994. Despite spending trillions of Yen, the campaign only marginally stemmed the rise of the Yen.

Meanwhile, the Japanese economy has been mired in what could be termed the “world’s longest recession, dating back to the 1980’s. It’s clear that the cheap-Yen policy, designed to promote exports, hasn’t benefited the Japanese economy. The new administration, hence, has indicated a shift in strategy, away from export dependence and towards domestic consumption.

Ironically, the nascent Japanese economic turnaround is once again being driven by exports. Fujii is no doubt cognizant of this, and doesn’t want to jeopardize the recovery for the sake of ideology. For example, Toyota Corporation has indicated that a 1% appreciation in the Yen against the Dollar costs the company $400 million in operating income. In addition, while a strong Yen increases the purchasing power of Japanese consumers, an overly strong Yen can lead to deflation, as consumers forestall spending in anticipation of lower prices down the road.

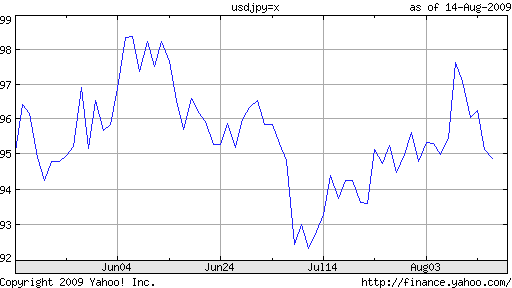

In other words, Fujii is certainly not a proponent of Japan’s recent runup, but his stance is more nuanced than initially understood. “Fujii is basically saying currencies should reflect economic fundamentals and that it is wrong to manipulate their moves to lower the yen for the sake of exporters,” offered one strategist. This, the markets finally seem to understand, and the Yen has actually reversed course over the last week. After all, “A yen in the 80s is excessive,” given the context of record low interest rates and a economy that is still contracting.

In the near-term, then, it doesn’t even make sense to talk about intervention. It seems the markets were getting ahead of themselves in this regard. It doesn’t make sense to price out the possibility of intervention when interevention shouldn’t be a factor in the first place. If on the other hand, the Yen continues to appreciate, then Fujii may have consider how fixed his principles really are.

The semiannual meetings of the “G” countries – whether the G7, G8, G20, etc. – are always closely monitored by currency analysts. Especially close attention is paid to the official communique, which often includes an assessment of current exchange rates.

The communique is rarely so straightforward as to indicate if, when, and where the Gs will intervene. Nonetheless, it is often full of intimations, and analysts often spend days parsing its rhetoric for clues. During this period, it’s not uncommon for the forex markets to witness increased volatility, as investors try to come to consensus about what to expect in the months following the meeting. This is because unlike Central Banks, which often face difficulties in unilaterally trying to influence their currencies, the G7 is usually able to achieve its desired goal: “A study last year by ECB economist Marcel Fratzcher found the G7 was successful in moving within a year currencies on 80 per cent of the 29 occasions it tried to do so since 1975.”

However, the current meeting, which is being held in Instanbul, Turkey,may break from this tradition. It’s not clear exactly what motivated the (potential) decision not to release a communique, which has been an important policy tool for the last three decades. Perhaps, policymakers have realized that their are other, better forums to discuss currency issues, namely the G20, which met last week in Pittsburgh, USA.

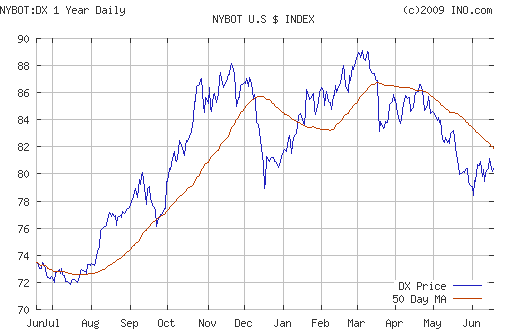

The timing of the decision is somewhat odd, given that exchange rate and other economic imbalances are proliferating. In fact, in press conferences held before and after the official G7 meetings, policymakers and Central Bankers have been forthcoming about such imbalances. Jim Flaherty, Finance Minister of Canada, sounded off on the RMB, which has stalled in its appreciation for over a year: “They (China) have a position that they are relaxing their currency, relaxing the restrictions on their currency gradually over time,” he said. Meanwhile, ECB Governor Jean-Claude Trichet voiced concerns about the Dollar, which has slide 15% against the Euro so far this year.

Ironically given the G7’s refusal to act, there is actually a strong conensus that the Dollar’s slide is generally bad for the global economy, especially in the context of the nascent recovery. A cheaper Dollar not only affects the export competitiveness of countries in Asia, but is also partially responsible for surging commodity prices. There is also a general belief that volatile (perhaps unstable is a better word) exchange rates are not conducive to economic and financial stability.