Understanding the Greece Situation

With this post, I want to try to clarify the Greek fiscal crisis. The problem is that it’s not clear exactly how serious the problem is, because most of the media coverage of the crisis has been directed towards the financial markets’ perception of it, rather than its underlying fundamentals. In the end, I think it’s important to understand both.

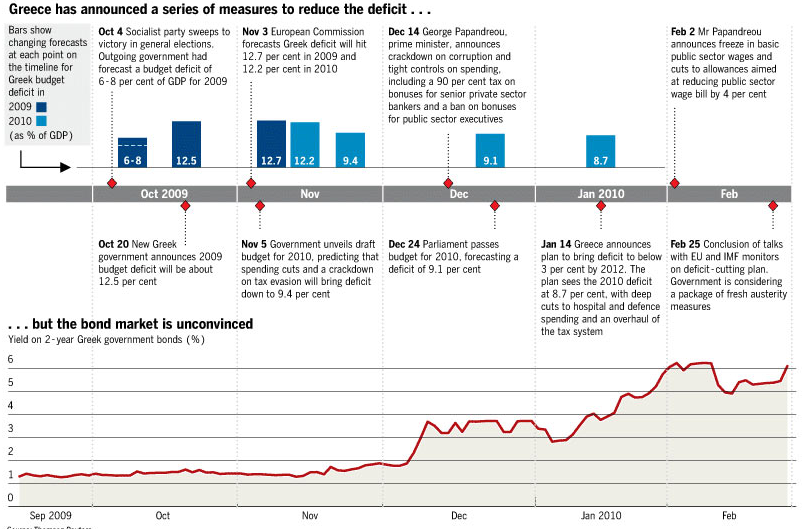

The Financial Times published a great timeline that shows perception and reality side-by-side. While there were certainly other important developments that bear in Greece’s fiscal position (in addition to those listed below), you can see that financial markets are basically making their own reality. For example, there was hardly a response to the October announcement that Greece’s budget deficit would be 12.7%, which was 5% higher than earlier estimates. In fact, the markets only became bearish on Greek debt after it the government announced that it would try to bring the debt down to 9.4% through various measures.

Apologists for the markets would be right to wonder why investors should be inclined to believe the government of Greece when it said it could control the budget deficit. Fair enough. Still, one has to wonder why the markets suddenly started worrying about Greece’s fiscal problems, when only a couple months ago, the possibility of a whopping 12.7% budget deficit barely caused investors to blink. Besides, the credit crisis has been raging since 2008, which means the markets have had plenty of time to digest the implications of recession for Greece’s fiscal position.

These days, where is a financial crisis, chances are derivatives are not far removed. As credit default swap spreads (i.e. the cost of insuring against default by Greece on its loan obligations) have risen, so have concerns that this is a bona fide crisis. “It’s like the tail wagging the dog…There is a knock-on effect, as underlying positions begin to seem riskier, triggering risk models and forcing portfolio managers to sell Greek bonds,” said one portfolio manager. From this perspective, it almost looks like this “crisis” is being completely manufactured by speculators for the sake of profit. Summarized another analyst, “It’s like buying fire insurance on your neighbor’s house — you create an incentive to burn down the house.”

To be fair, Greece also played a role in derivatives speculation, and on some level, it was even more nefarious than the speculators. Assisted by Goldman Sachs (who is now betting on Greek default [how un-ironic that is!]), Greece entered into a series of swap agreements last decade, which it used to conceal its true debt burden. “By using an historical exchange rate that didn’t accurately denote the market value of the euro, Goldman effectively advanced Greece a €2.8 billion loan. Under EU accounting rules—which were tightened in 2008—Greece wasn’t obliged to include the loan in overall public debt on its books.” Now that those transactions have been uncovered and the truth is coming to light, financial markets are rightly re-evaluating the risk of further lending to Greece.

There is no question that Greece’s debt problems are serious. As to whether labeling it a crisis is necessary, that depends on your standards. Greece ranks near the top of the list on a variety of individual “debt sustainability” criteria. At 94.6% of GDP, it’s net debt is among the highest in the world. Its projected 2010 budget deficit is also high, though not the highest. Its cost of borrowing is also significantly higher than projected GDP growth, which means that net debt will continue to grow until a budget surplus can be produced. When you average these measures together, it appears that Greece’s debt problems are the most unsustainable of any country in the world. But this is hardly news.

On the other hand, the weighted average of the maturity of Greek debt is 7.7 years, well above average, and plenty of time (relatively) for Greek to sort through this mess and secure new lenders. Towards the latter end, it has hired a former bond trader to head its debt management agency. In order to improve its fiscal position, it has announced a series of austerity measures, including budget cuts, tax increases, wage cuts for public-sector employees, and stricter laws against tax evasion.

At this point, a ratings downgrade looks inevitable, and some analysts think the crisis has already become self-fulfilling. As borrowing costs rise, it only makes it more likely that Greek will default, which causes rates to rise further, and so on. On the other hand, Greek politicians are being forthright about their position (“Greece’s finance minister, George Papaconstantinou, remarked this week: ‘People think we are in a terrible mess. And we are.’ “) and have a plan for rectifying the situation. There is cause for skepticism here, but also for hope. And that goes not just for Greece, but also for the Euro.