The Diminished Case for Chinese Yuan Appreciation

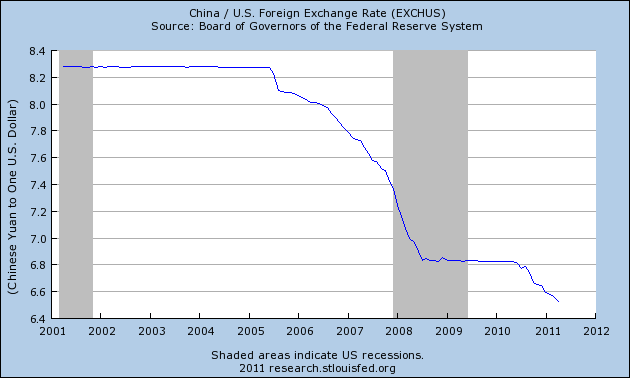

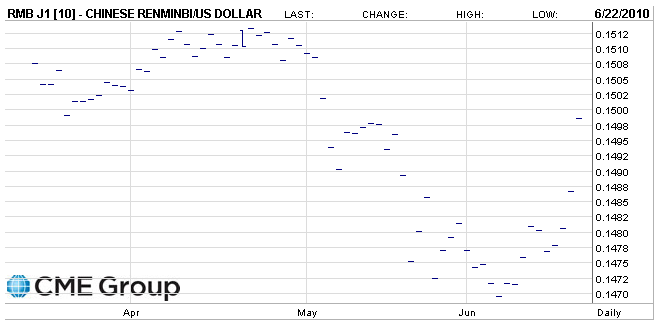

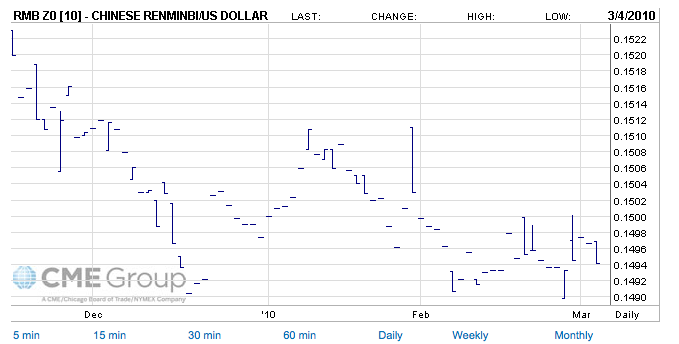

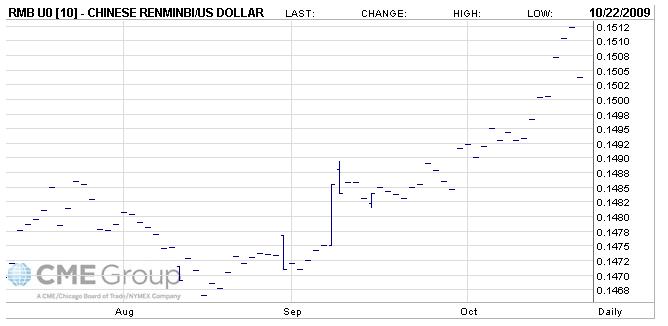

The Chinese yuan has appreciated by more than 27.5% since 2005, when the People’s Bank of China (“PBOC”) formally acceded to international pressure and began to relax the yuan-dollar peg. For China-watchers and economists, that the Yuan will continue to appreciate is thus a given. There is no question of if, but rather of when and to what extent. But what if the prevailing wisdom is wrong? What if the yuan is now fairly valued, and economic fundamentals no longer necessitate a further rise?

Prior to the 2005 revaluation, economists had argued that the yuan (also known as the Chinese RMB) was undervalued by 15% – 40%, and American politicians had used this as a basis for proposing a 27.5% across-the-board tariff on all Chinese imports. Given that the yuan has now appreciated by this exact margin (and by even more when inflation is taken into account), shouldn’t this alone be enough to silence the critics, without even having to look at the picture on the ground? How can Senator Charles Schumer continue to press for further appreciation when the yuan’s rise exceeds his initial demands? Alas, election season is upon us, and we can’t hope to make political sense out of this issue. We can, however, attempt to analyze the economic sense of it.

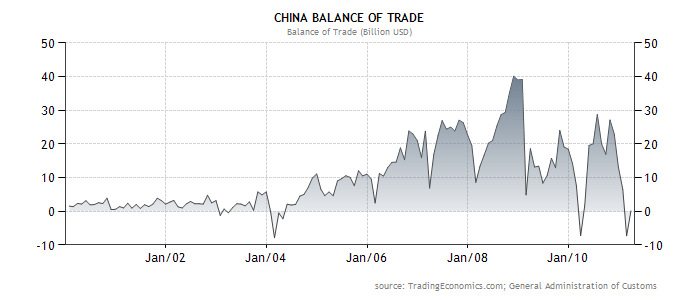

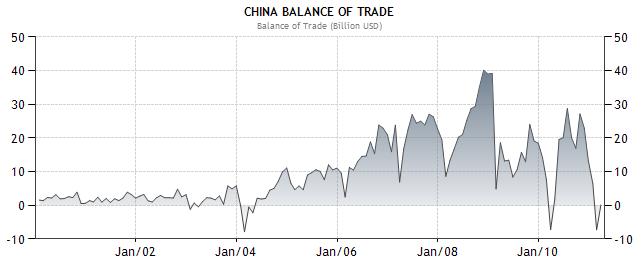

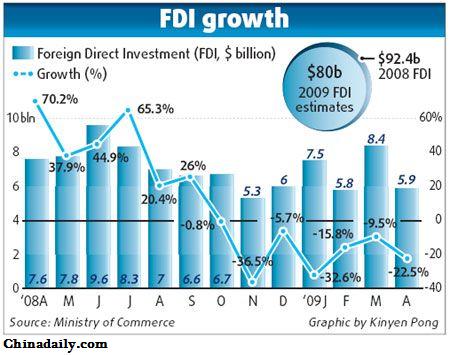

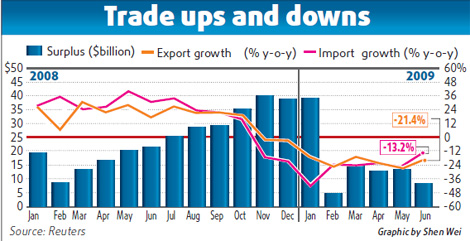

China manipulates the value of the yuan in order to give a competitive advantage to Chinese exporters, goes the conventional line of thinking. Look no further than the Chinese trade surplus for evidence of this, right? As it turns out, China’s trade surplus is shrinking rapidly. In 2006, it was a whopping 11% of GDP. Last year, it had fallen to 5%, and it is projected by the World Bank to settle below 3% for each of the next two years. Thanks to a first quarter trade deficit – the first in over seven years – China’s trade surplus may account for a negligible portion (~.2%) of GDP growth in 2010.

With this in mind, why would the PBOC even think about allowing the RMB to appreciate further? According to one perspective, the narrowing trade imbalance is only temporary. When commodities prices settle and global demand fully recovers, a wider trade surplus will follow. In fact, the IMF forecasts China’s current surplus will rise to 8% by 2016. As you can see from the chart below (courtesy of The Economist), however, the IMF’s forecasts have proven to be too pessimistic for at least the last three years, and it now has very little credibility. Besides, China’s economy is gradually reorienting itself away from exports and towards domestic spending. As a resident of China, I can certainly attest to this phenomenon, and the last few years has seen an explosion in the number of cars on the road, domestic tourism, and conspicuous consumption.

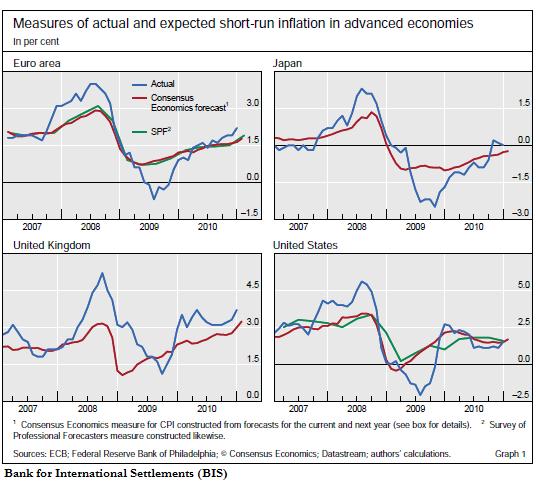

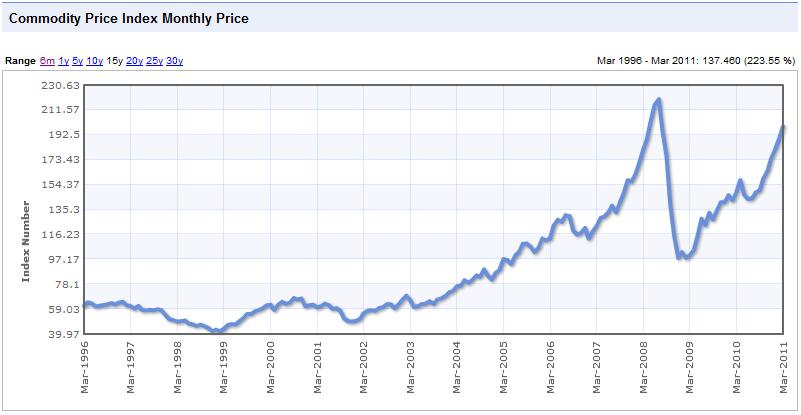

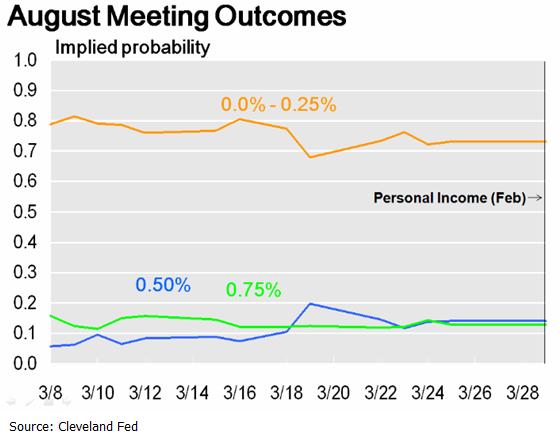

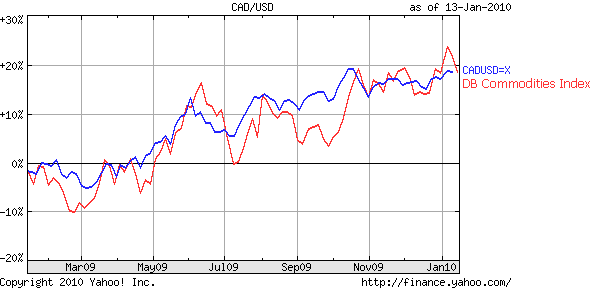

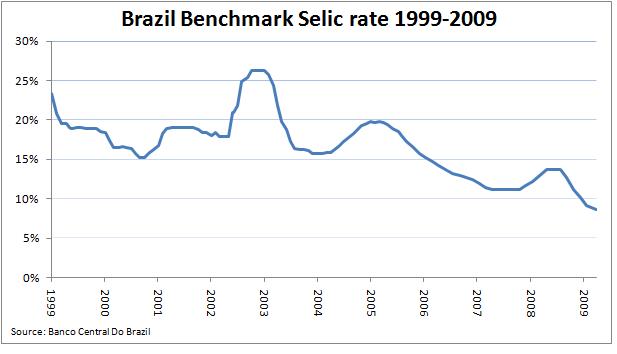

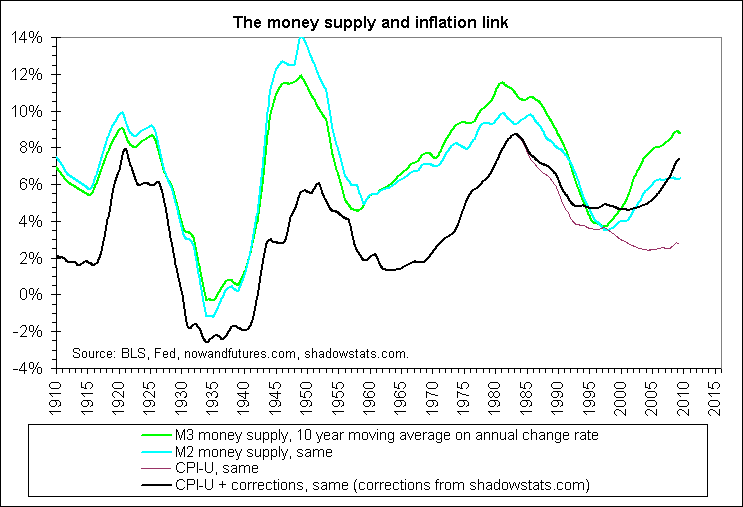

A better argument for further RMB appreciation comes in the form of inflation. At 5.4%, inflation is officially nearing a 3-year high, and there is evidence that the PBOC already recognizes that allowing the RMB to keep rising represents its best tool for containing this problem. It has already raised banks’ required reserve ratio several times, but there is a limit to what this can accomplish. Meanwhile, the PBOC remains reluctant to raise interest rates because it will invite further “hot-money” inflows (estimated at more than $100 Billion per year, if not much higher) and potentially destabilize the banking sector. By raising the value of the yuan, the PBOC can blunt the impact of rising commodities prices and other inflationary forces.

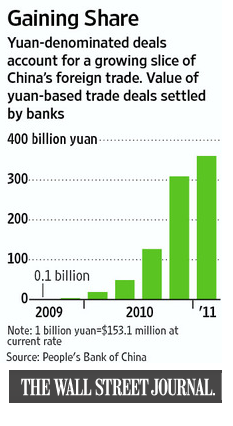

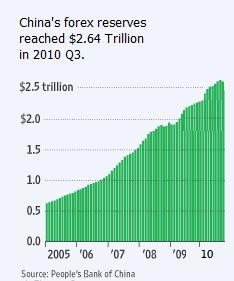

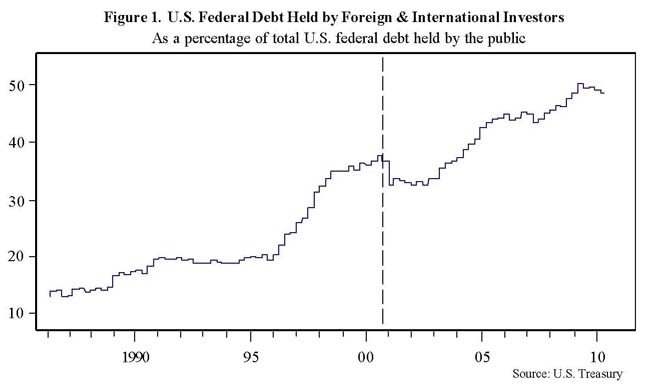

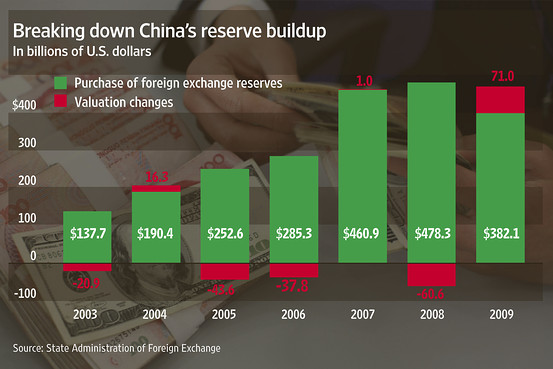

In fact, some think that the PBOC will quicken the pace of appreciation, a view that as supported by last month’s .9% rise. Others think that a once-off appreciation would be more effective, and is hence more likely. This would not only remove the motivation for further hot-money inflows, but would also reduce the PBOC’s need to continue accumulating foreign exchange reserves. At $3 trillion+ ($1.15 trillion of which are held in US Treasury Securities), these reserves are already a massive headache for policymakers. Merely stating the obvious, PBOC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan has officially called the reserves “really too much.” (It’s worth pointing out that the promotion of the yuan as an international currency is backfiring in some ways, causing the reserves to balloon even faster).

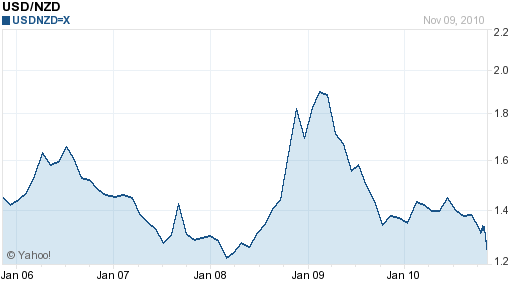

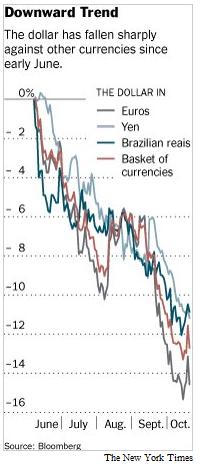

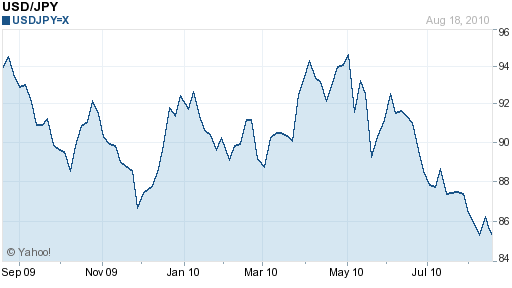

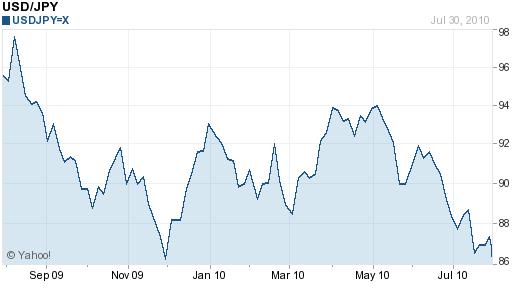

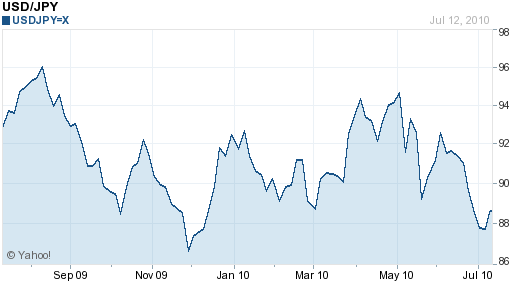

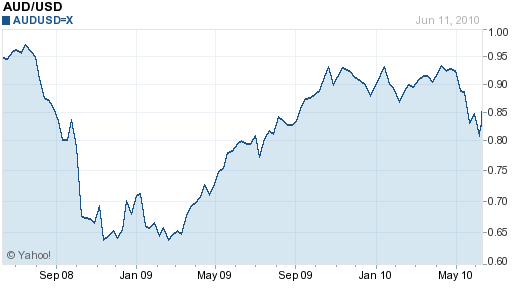

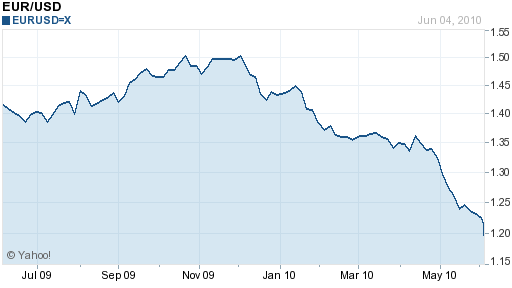

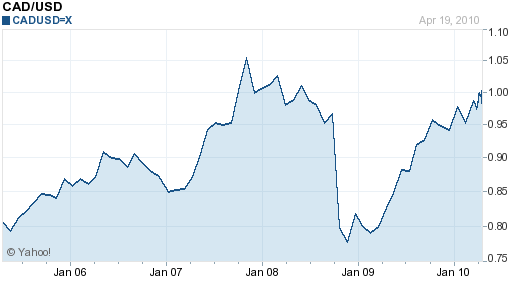

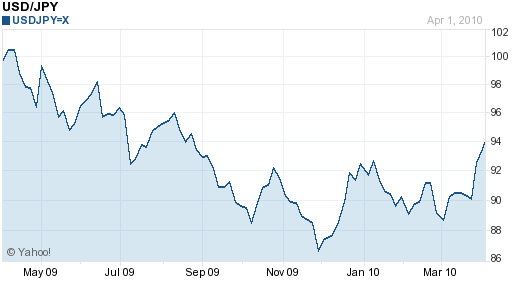

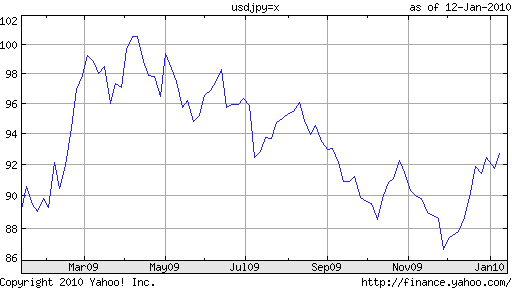

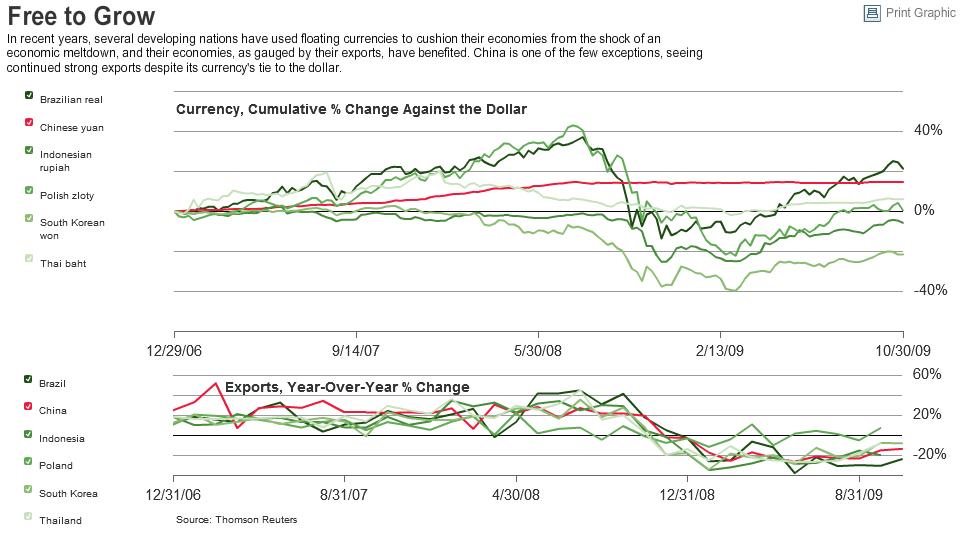

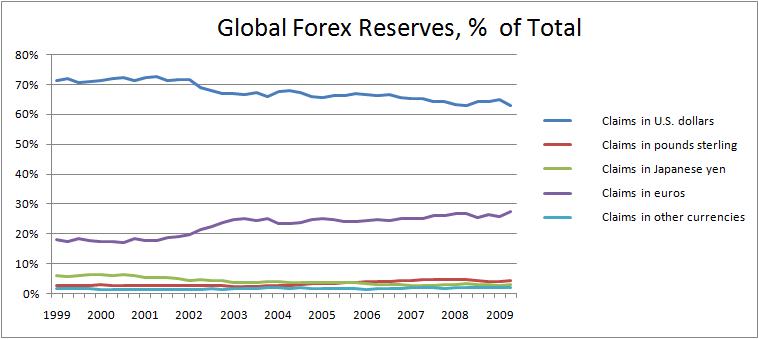

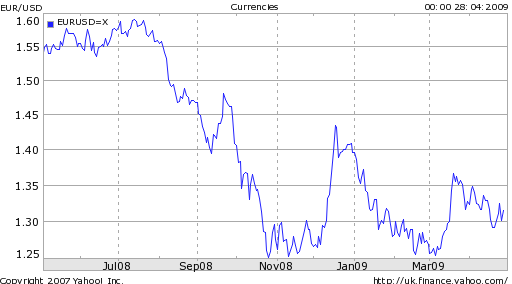

For the record, I think that the Chinese yuan is pretty close to being fairly valued. That might seem like a ridiculous claim to make when Chinese wages and prices are still well below the global average. Consider, however, that the same is true for the majority of emerging market economies, including those that don’t peg their currencies to the dollar. That doesn’t mean that the yuan won’t – or that it shouldn’t – continue to rise. In fact, the PBOC needs to do more to ensure that the Yuan appreciates evenly against all currencies, since most of the yuan’s rise to-date has taken place relative to the US Dollar. It’s merely a commentary that the PBOC is close to fulfilling the promises it has made regarding the yuan, and going forward, I think that observers should expect that its forex policy will be reconfigured to promote domestic macroeconomic policy objectives.

For the record, I think that the Chinese yuan is pretty close to being fairly valued. That might seem like a ridiculous claim to make when Chinese wages and prices are still well below the global average. Consider, however, that the same is true for the majority of emerging market economies, including those that don’t peg their currencies to the dollar. That doesn’t mean that the yuan won’t – or that it shouldn’t – continue to rise. In fact, the PBOC needs to do more to ensure that the Yuan appreciates evenly against all currencies, since most of the yuan’s rise to-date has taken place relative to the US Dollar. It’s merely a commentary that the PBOC is close to fulfilling the promises it has made regarding the yuan, and going forward, I think that observers should expect that its forex policy will be reconfigured to promote domestic macroeconomic policy objectives.

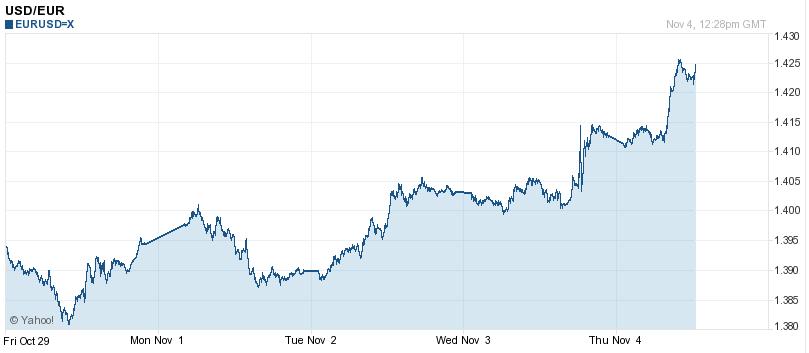

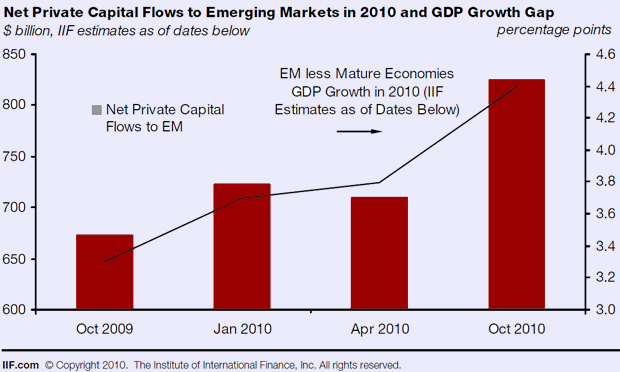

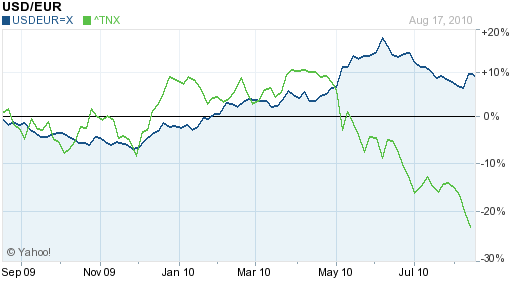

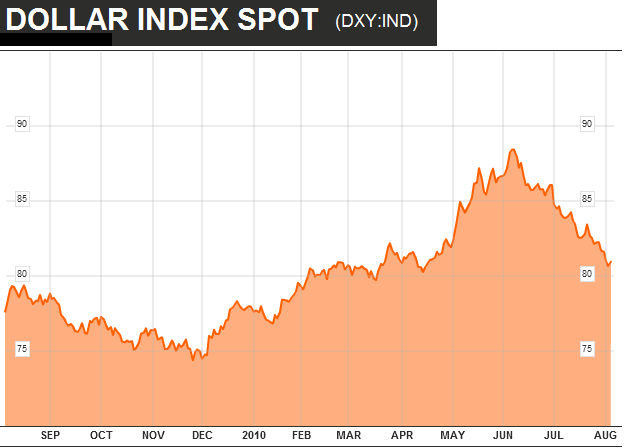

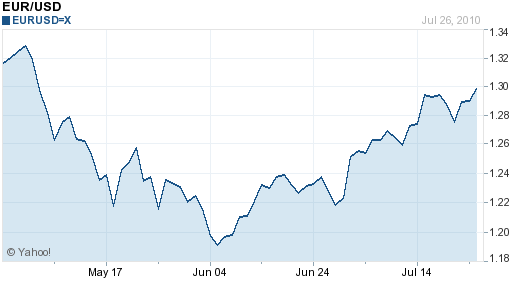

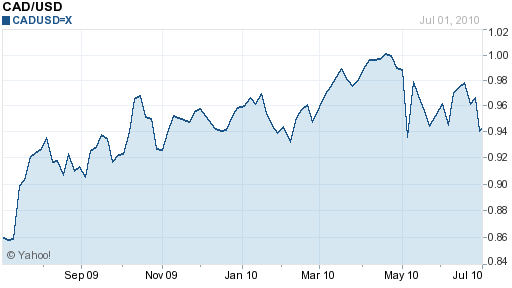

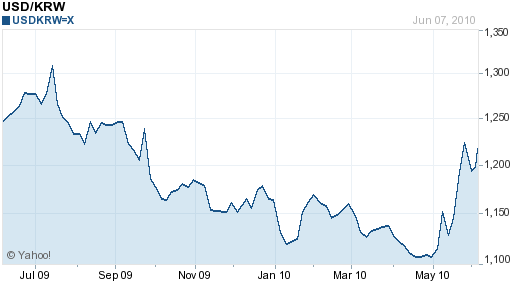

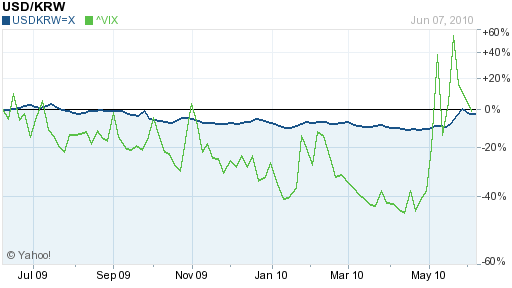

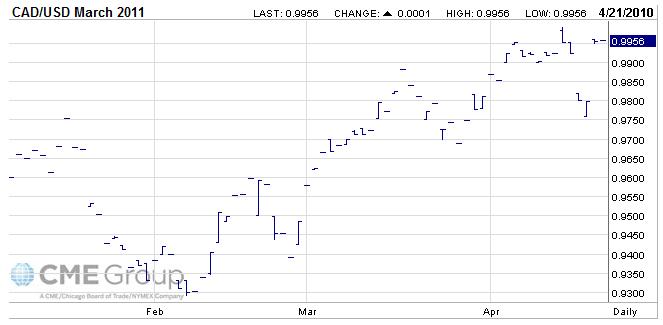

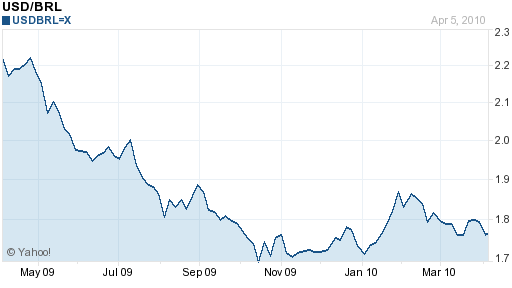

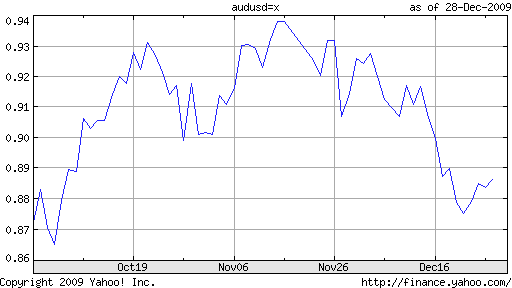

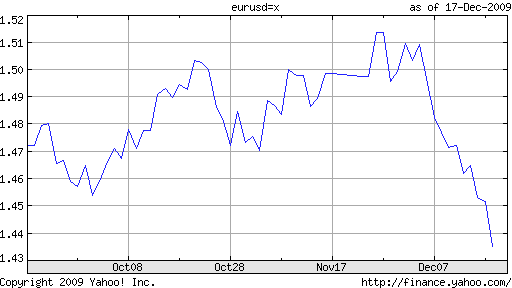

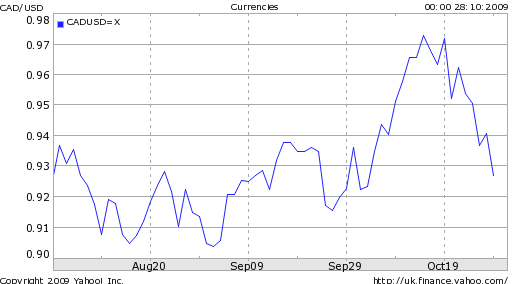

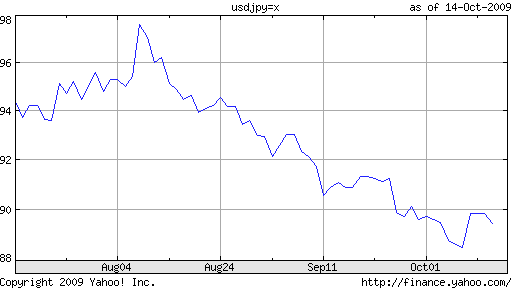

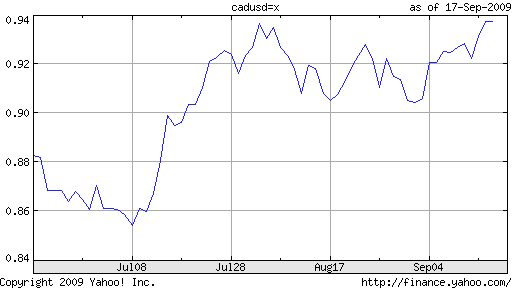

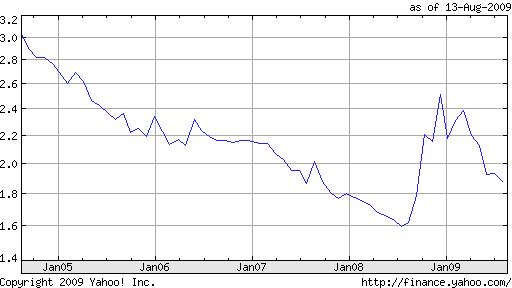

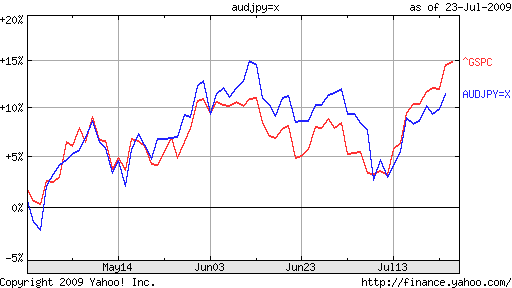

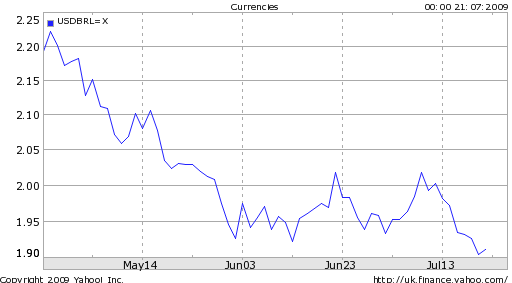

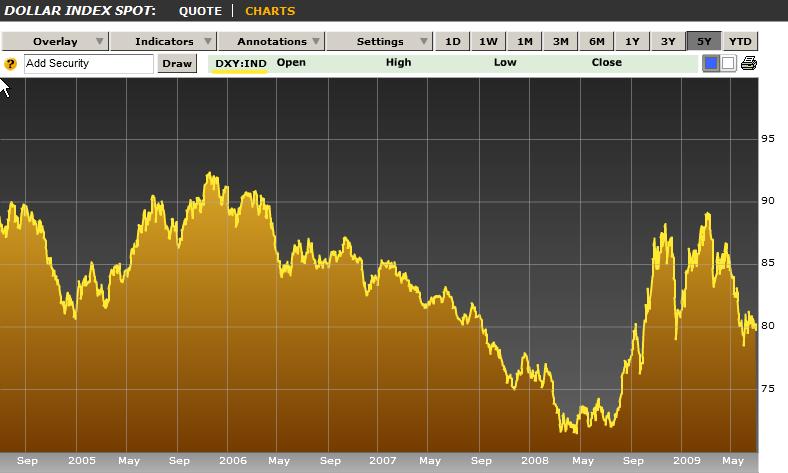

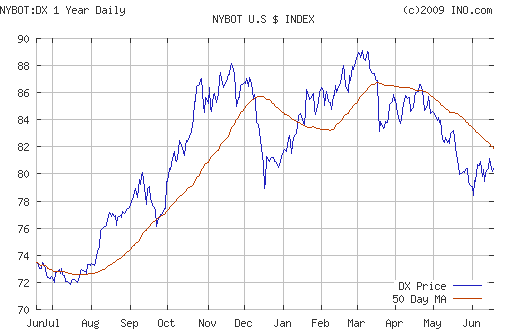

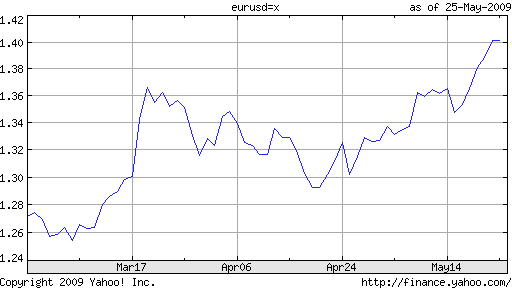

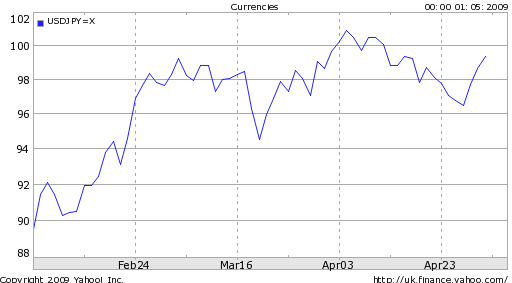

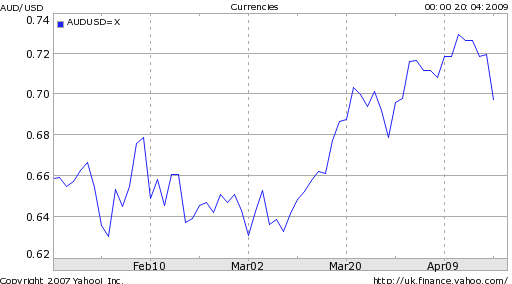

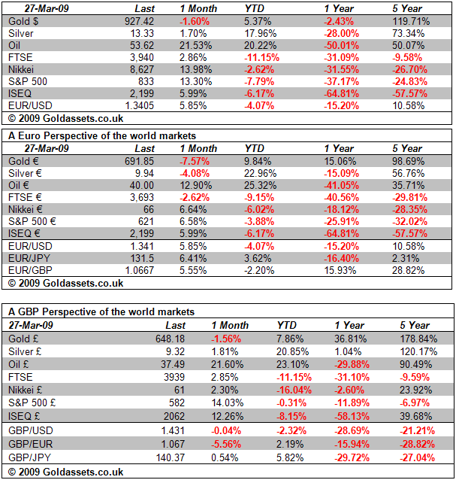

A theme in forex markets (as well as on the Forex Blog) is that as the Dollar has declined, virtually every other asset/currency has risen. The rationale for this phenomenon is that the global economic recovery is boosting risk appetite, such that investors are now comfortable looking outside the US for yield. However, this market snapshot may have to be tweaked slightly, in accordance with a recent WSJ article (

A theme in forex markets (as well as on the Forex Blog) is that as the Dollar has declined, virtually every other asset/currency has risen. The rationale for this phenomenon is that the global economic recovery is boosting risk appetite, such that investors are now comfortable looking outside the US for yield. However, this market snapshot may have to be tweaked slightly, in accordance with a recent WSJ article (

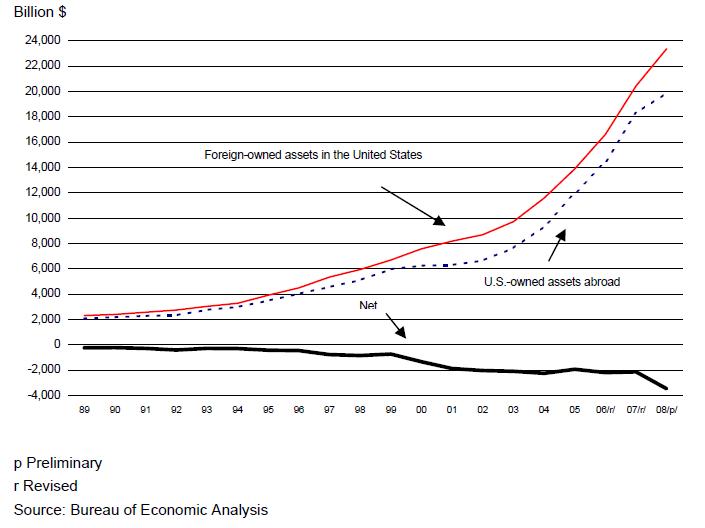

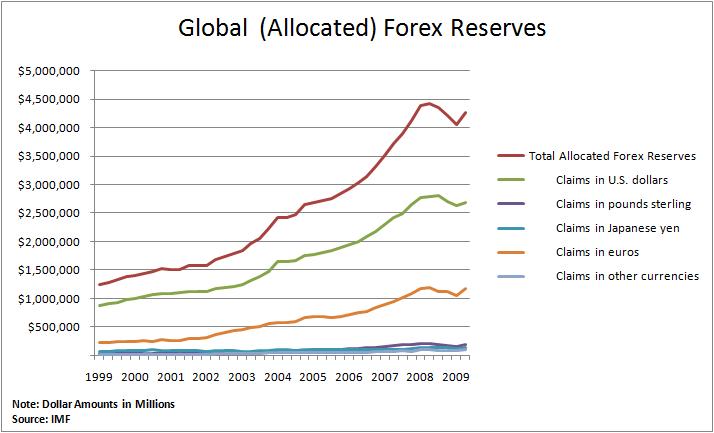

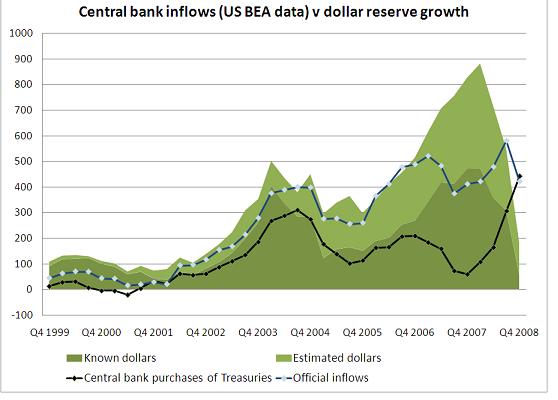

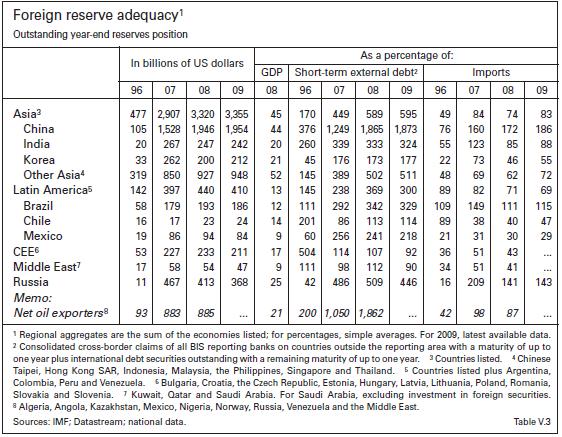

Given such robustness, it’s clear that the impetus to continue accumulating reserves has eroded slightly. Central Banks have also come to realize how vulnerable they are to credit and currency risk, vis-a-vis the allocation of their reserves, which means that the best alternative going forward is probably to start investing in commodities and/or domestic economic initiatives. China has already begun to move in this direction.

Given such robustness, it’s clear that the impetus to continue accumulating reserves has eroded slightly. Central Banks have also come to realize how vulnerable they are to credit and currency risk, vis-a-vis the allocation of their reserves, which means that the best alternative going forward is probably to start investing in commodities and/or domestic economic initiatives. China has already begun to move in this direction.

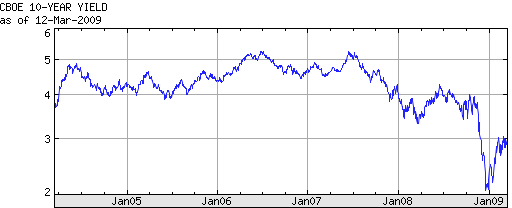

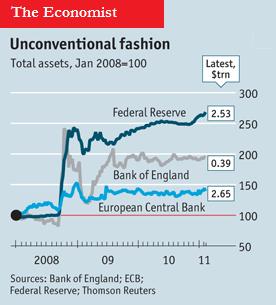

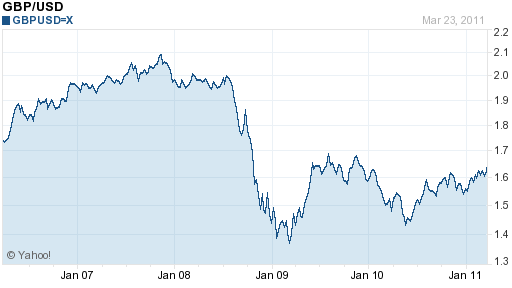

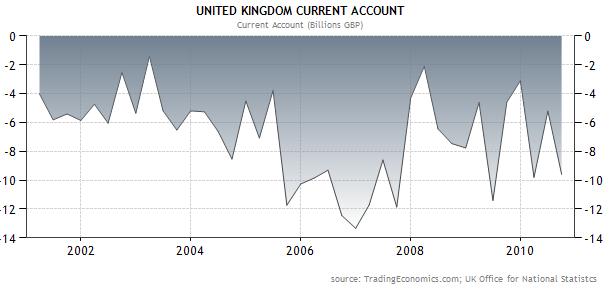

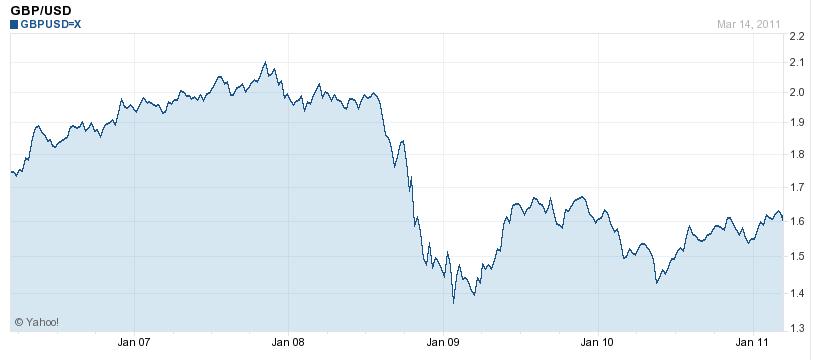

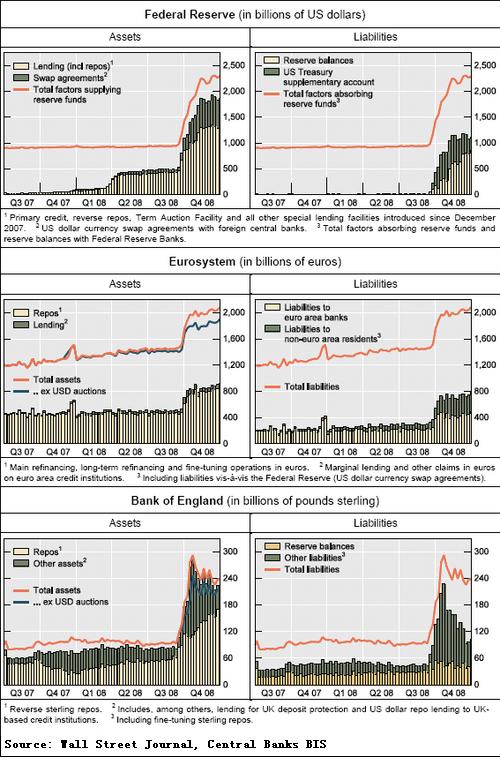

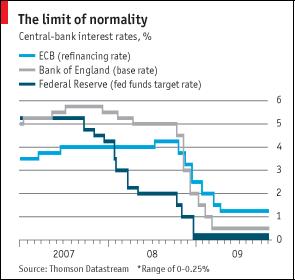

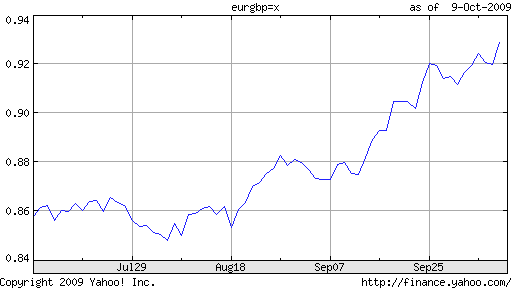

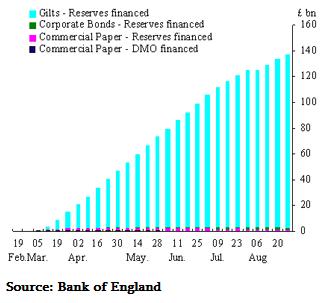

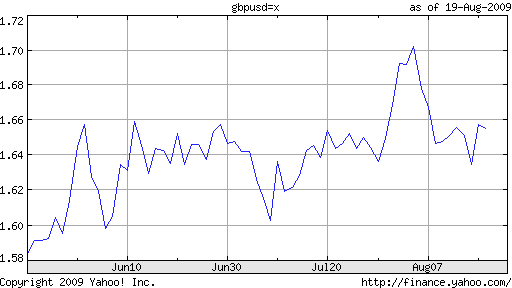

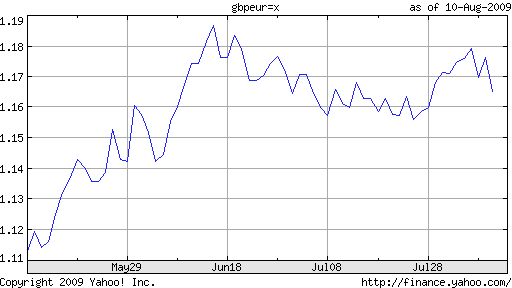

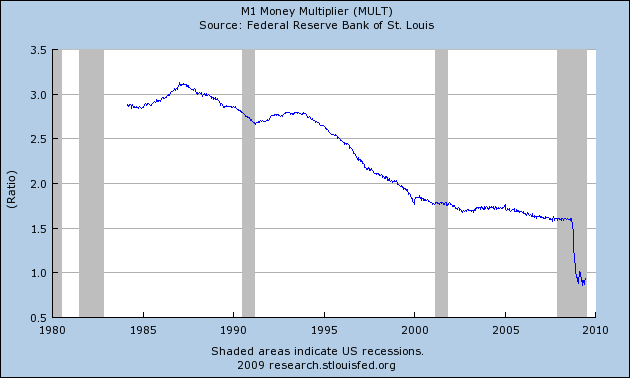

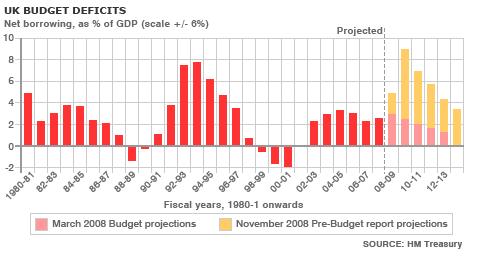

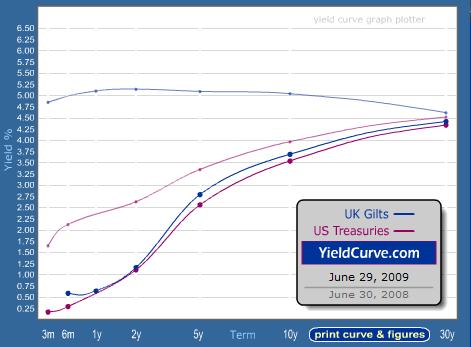

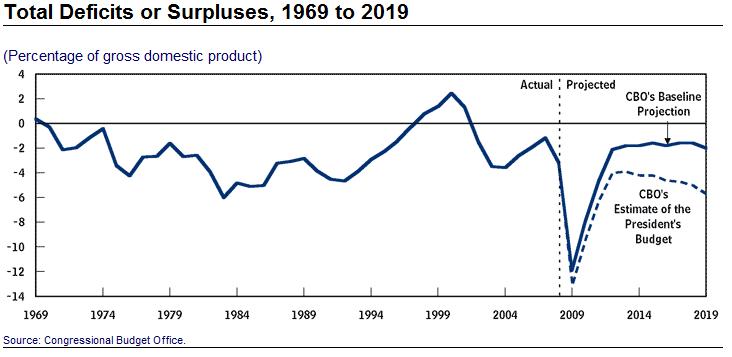

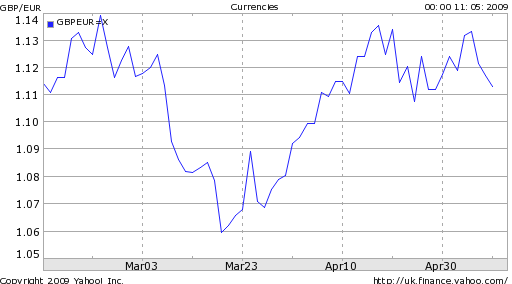

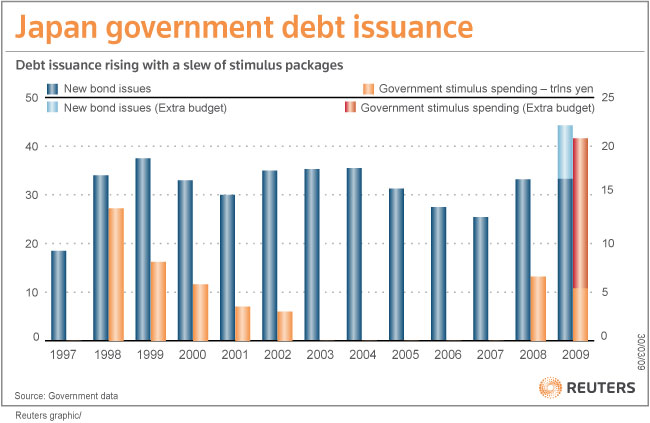

In short, there is potentially more downside than upside to these efforts, especially as far as the Pound is concerned. The BOE’s easy money policy makes the Pound an unattractive buy in the short term, while its QE program could stoke inflation in the long-term, without much benefit to the economy. Furthermore, it will be difficult to rein in this program because of the perennial budget deficits of the government, which “must sell about 900 billion pounds of gilts over five years…The Bank of England will buy a third of these gilts.” The recent rise in government bond yields as well as the rising cost of bond insurance (i.e. credit default swap premiums) confirm that investors are growing increasingly nervous. According to a

In short, there is potentially more downside than upside to these efforts, especially as far as the Pound is concerned. The BOE’s easy money policy makes the Pound an unattractive buy in the short term, while its QE program could stoke inflation in the long-term, without much benefit to the economy. Furthermore, it will be difficult to rein in this program because of the perennial budget deficits of the government, which “must sell about 900 billion pounds of gilts over five years…The Bank of England will buy a third of these gilts.” The recent rise in government bond yields as well as the rising cost of bond insurance (i.e. credit default swap premiums) confirm that investors are growing increasingly nervous. According to a

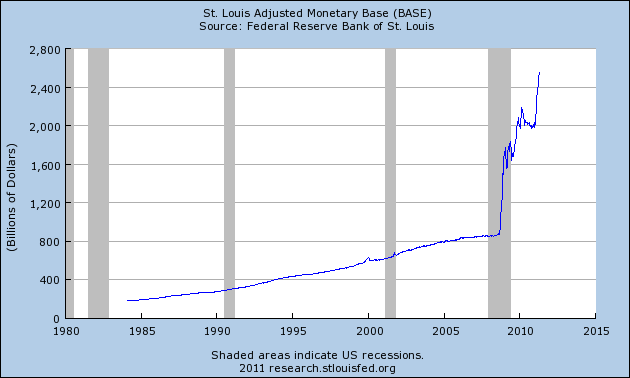

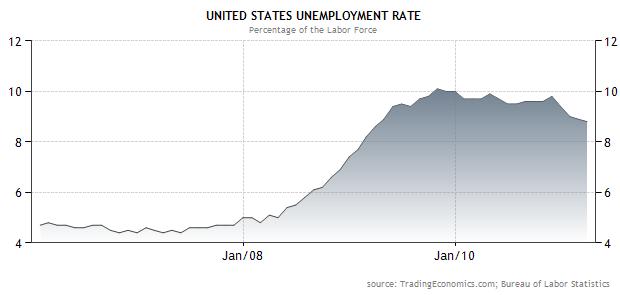

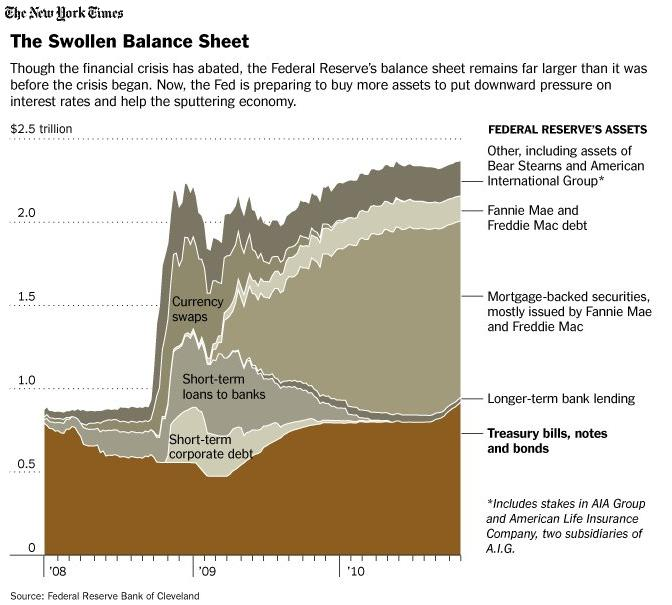

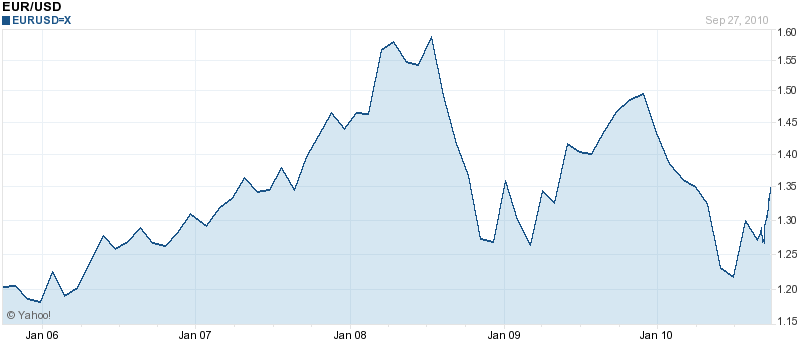

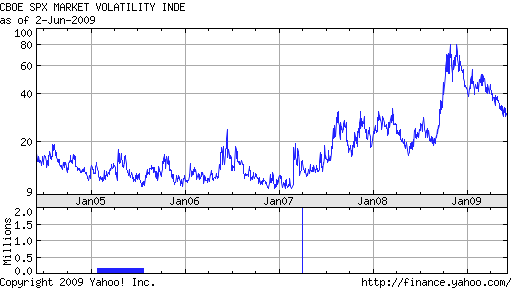

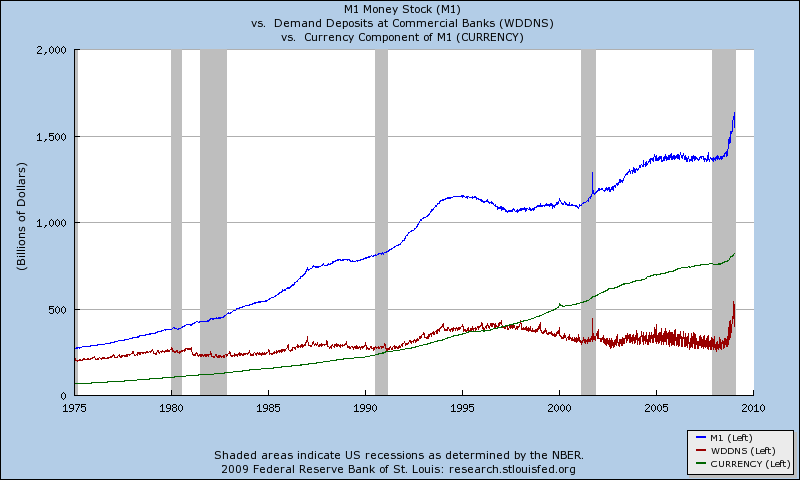

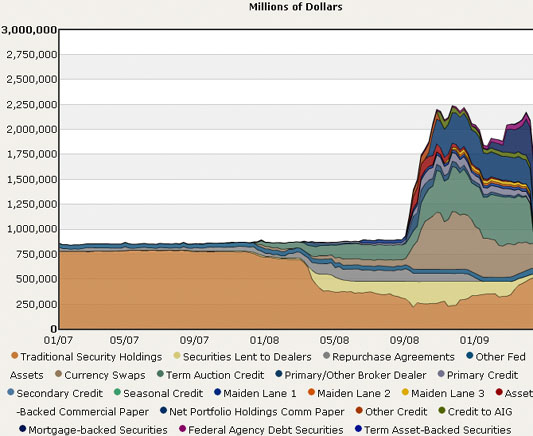

If the current rally is to be seen as “legitimate,” then perhaps the worst of the 2008-2009 recession is truly behind us, and the global financial system has been given a reprieve from a meltdown. The concern going forward then will naturally shift past the steps that governments and Central Banks are taking to fight the crisis, towards the long-term economic impact of those measures.

If the current rally is to be seen as “legitimate,” then perhaps the worst of the 2008-2009 recession is truly behind us, and the global financial system has been given a reprieve from a meltdown. The concern going forward then will naturally shift past the steps that governments and Central Banks are taking to fight the crisis, towards the long-term economic impact of those measures.

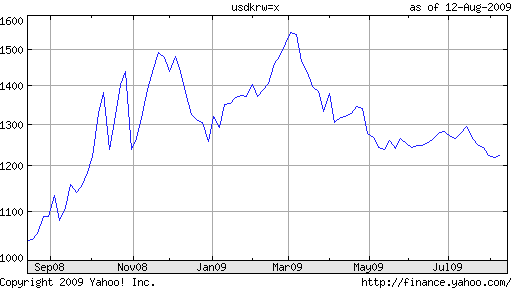

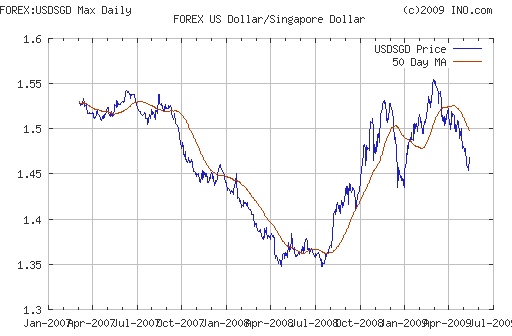

Now, with a global stock market rally underway and a modest economic recovery taking shape on the horizon, the Singapore Dollar has quickly erased almost half of its slide. The Central Bank naturally, is alarmed, and is threatening to intervene. While the MAS, itself, has thus far denied such a possibility, insiders suggested that “The Monetary Authority of Singapore will buy the U.S. dollar “‘f it falls below S$1.4700, around S$1.4690…’ [which] roughly equates with the strong end of the undisclosed

Now, with a global stock market rally underway and a modest economic recovery taking shape on the horizon, the Singapore Dollar has quickly erased almost half of its slide. The Central Bank naturally, is alarmed, and is threatening to intervene. While the MAS, itself, has thus far denied such a possibility, insiders suggested that “The Monetary Authority of Singapore will buy the U.S. dollar “‘f it falls below S$1.4700, around S$1.4690…’ [which] roughly equates with the strong end of the undisclosed

In fact, the Bank of England just announced a huge expansion in its program, increasing total debt buying (i.e. money printing) by $50 Billion. One analyst summarized the impact of this announcement on forex markets as follows: “The Bank of England’s aggressive stance with regard to quantitative easing is adding to concern about the economy and that is negative for sterling.” Not much nuance there….

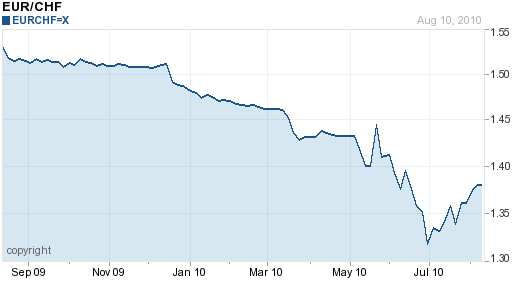

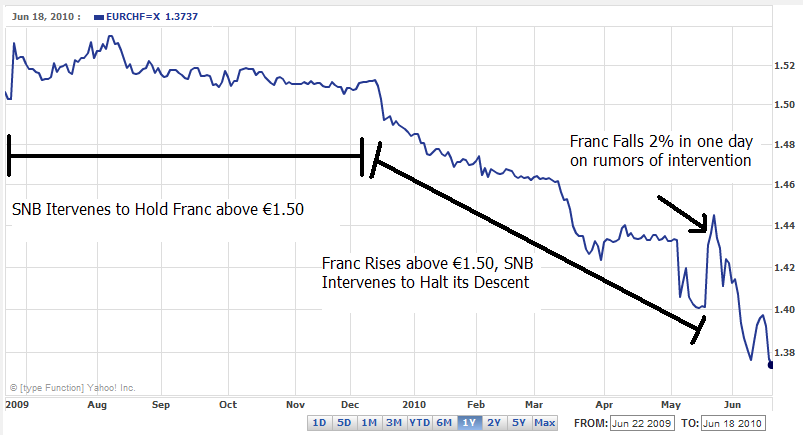

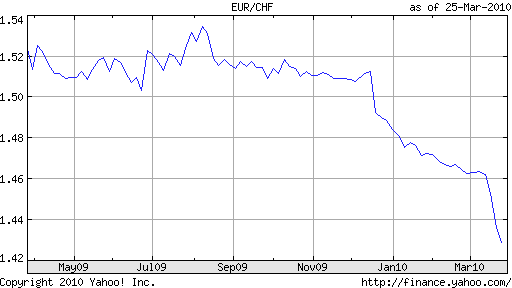

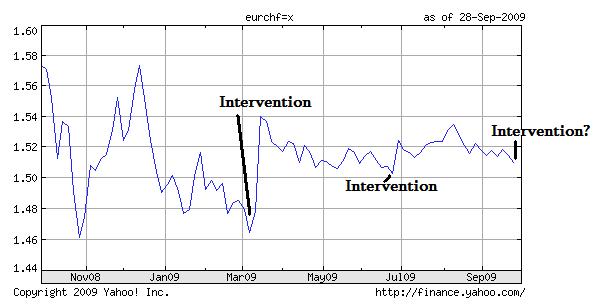

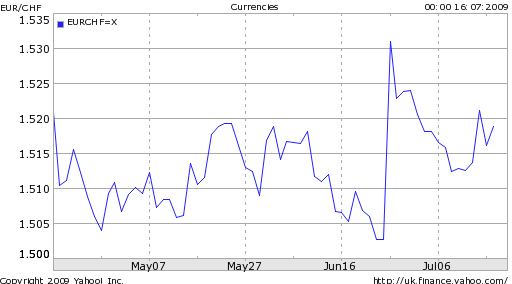

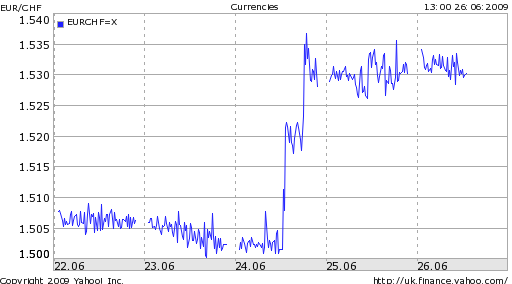

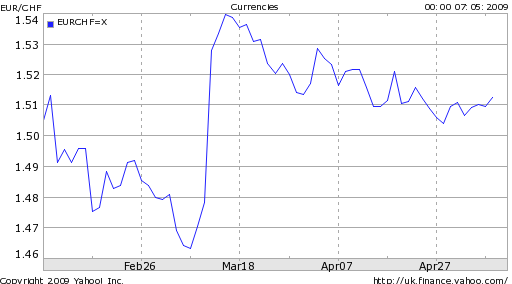

In fact, the Bank of England just announced a huge expansion in its program, increasing total debt buying (i.e. money printing) by $50 Billion. One analyst summarized the impact of this announcement on forex markets as follows: “The Bank of England’s aggressive stance with regard to quantitative easing is adding to concern about the economy and that is negative for sterling.” Not much nuance there…. It was unclear whether the Central Bank had chosen a magic threshold, such that a rise by the Franc above which would trigger a sale of Francs in the open market. Earlier in the week, one analyst asserted, “With the euro/franc exchange rate almost at pre-intervention levels – the euro jumped to a level above CHF1.52 after the SNB intervention in March from CHF1.4843 before the announcement – the stage is set for the SNB to

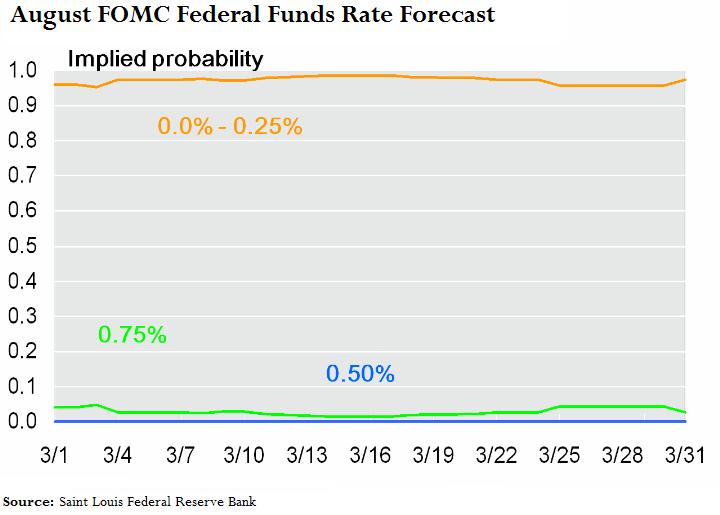

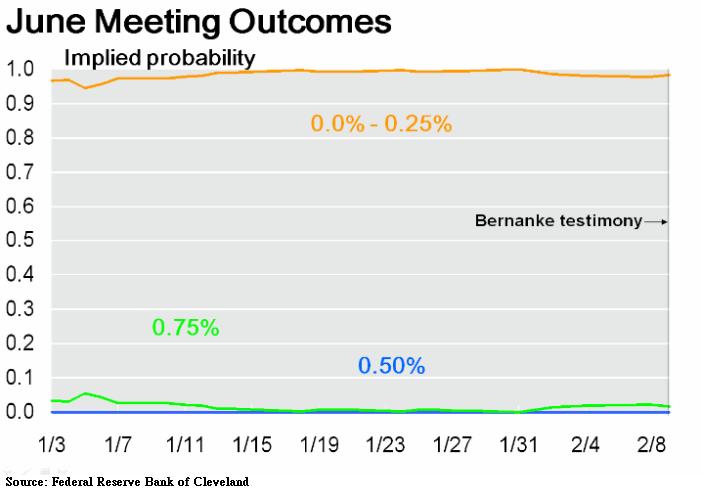

It was unclear whether the Central Bank had chosen a magic threshold, such that a rise by the Franc above which would trigger a sale of Francs in the open market. Earlier in the week, one analyst asserted, “With the euro/franc exchange rate almost at pre-intervention levels – the euro jumped to a level above CHF1.52 after the SNB intervention in March from CHF1.4843 before the announcement – the stage is set for the SNB to  Nonetheless, the Fed made a point of emphasizing that the economy seems to be stabilizing: “Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in March indicates that the

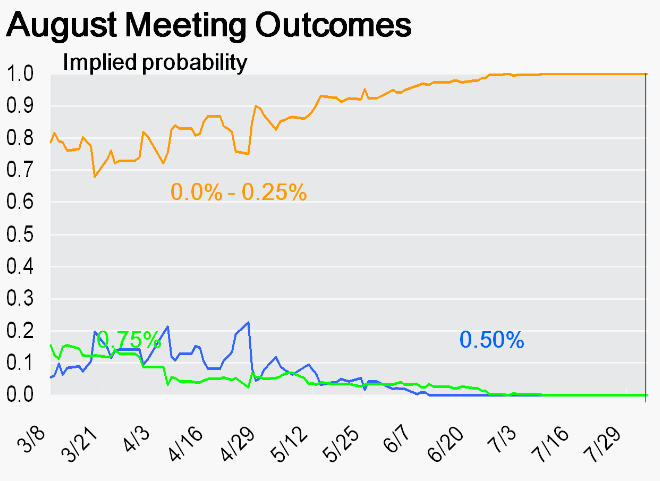

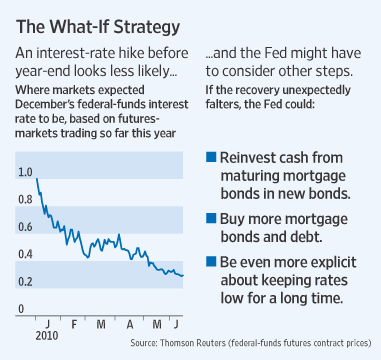

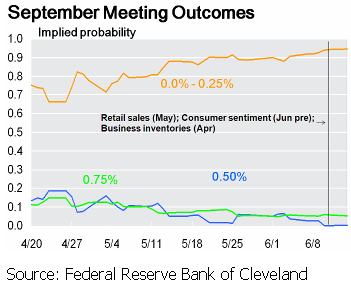

Nonetheless, the Fed made a point of emphasizing that the economy seems to be stabilizing: “Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in March indicates that the

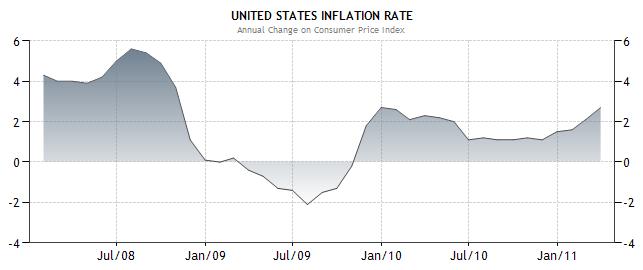

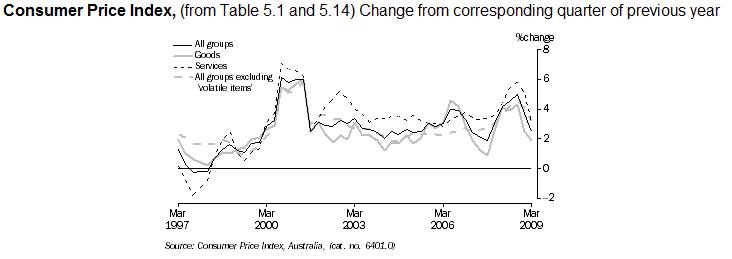

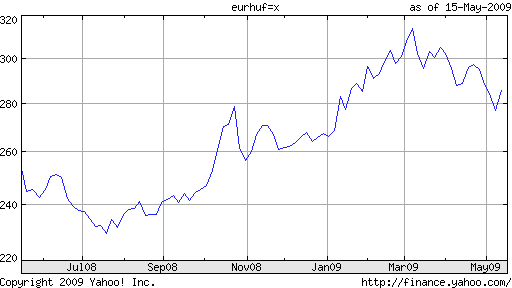

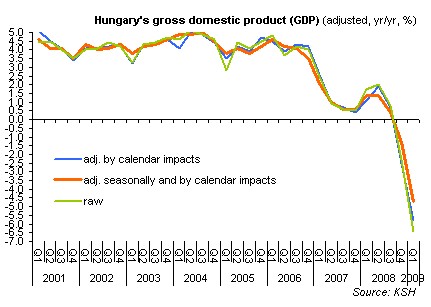

Given the abysmal economic situation, it is no surprise that inflation has moderated. Commodity prices are well below the record highs of 2008. Aggregate demand, and GDP by extension, are retreating in kind. According to one economist, ” ‘

Given the abysmal economic situation, it is no surprise that inflation has moderated. Commodity prices are well below the record highs of 2008. Aggregate demand, and GDP by extension, are retreating in kind. According to one economist, ” ‘

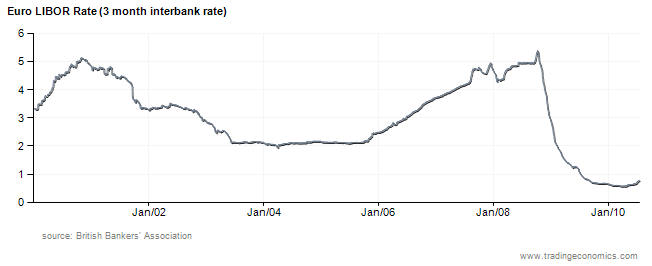

There are a few explanations. First of all, it’s possible that the ECB is selectively interpreting data as a basis for deriving a more optimistic economic forecast. Given the spate of recent bad news emanating from Europe, however, this seems unlikely. Besides, no less than Trichet himself has suggested that an economic recovery is

There are a few explanations. First of all, it’s possible that the ECB is selectively interpreting data as a basis for deriving a more optimistic economic forecast. Given the spate of recent bad news emanating from Europe, however, this seems unlikely. Besides, no less than Trichet himself has suggested that an economic recovery is

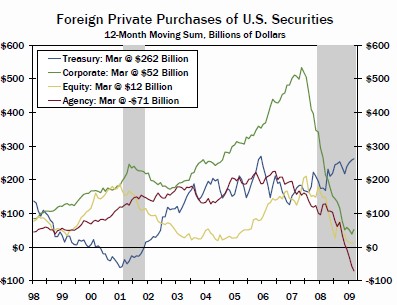

Even ignoring the potential political fallout from forex reserve diversification, such a move doesn’t really make practical sense. First of all, there isn’t a buyer sufficiently capitalized to relieve China of its US Treasury burden. “If China decided to sell off some of its U.S. Treasury holdings, it would scarcely be able to dump that in large blocks. And a partial selloff would surely lead to a slump in the Treasury market,

Even ignoring the potential political fallout from forex reserve diversification, such a move doesn’t really make practical sense. First of all, there isn’t a buyer sufficiently capitalized to relieve China of its US Treasury burden. “If China decided to sell off some of its U.S. Treasury holdings, it would scarcely be able to dump that in large blocks. And a partial selloff would surely lead to a slump in the Treasury market,