Emerging Market Currency Correlations Break Down

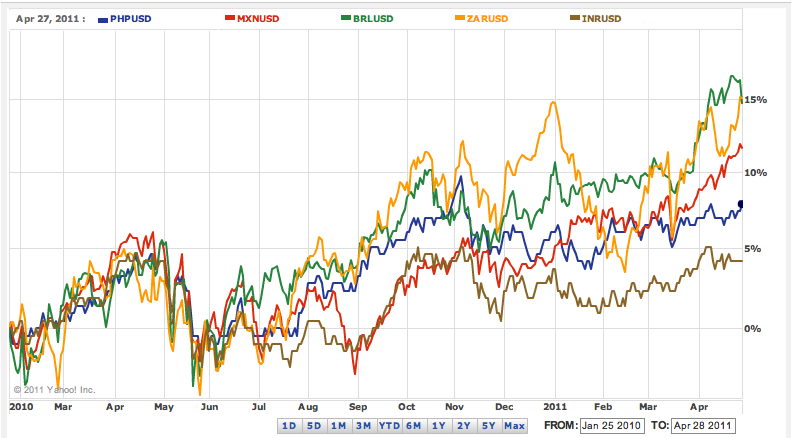

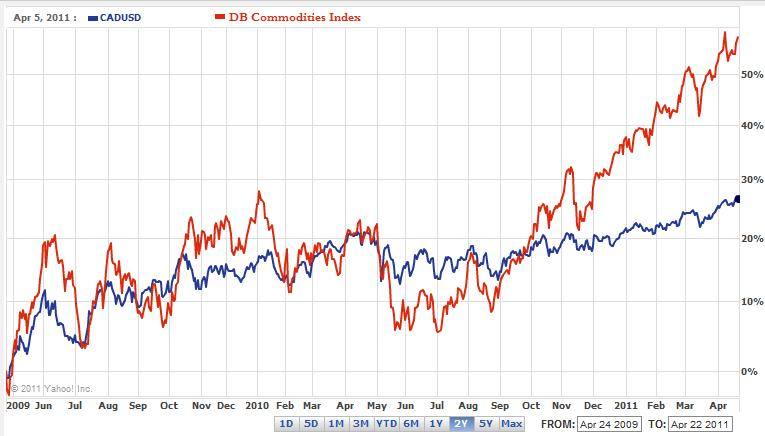

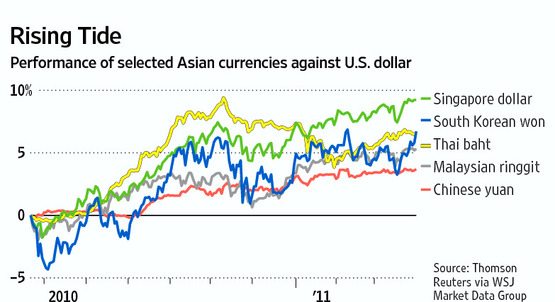

A picture is truly worth a thousand words. [That probably means I should stop writing lengthy blog posts and instead stick to posting charts and other graphics, but that’s a different story…] Take a look at the chart below, which shows a handful of emerging market (“EM”) currencies, all paired against the US dollar. At this time last year, you can see that all of the pairs were basically rising and falling in tandem. One year later, the disparity between the best and worst performers is already significant. In this post, I want to offer an explanation as to why this is the case, and what we can expect going forward.

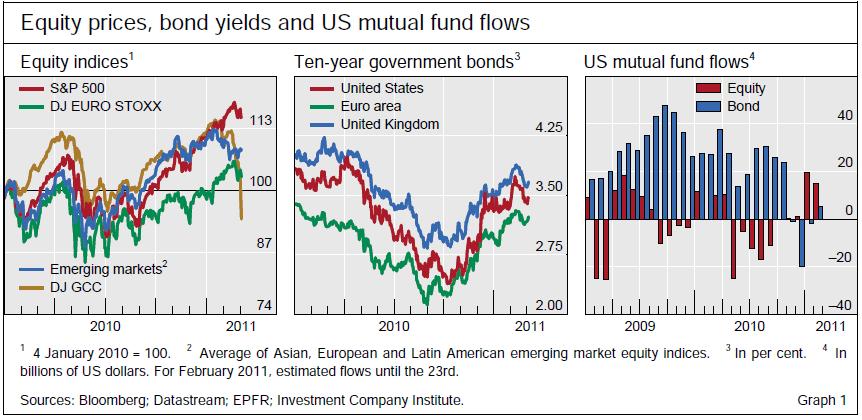

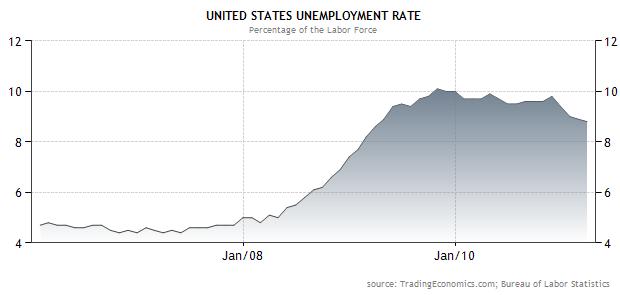

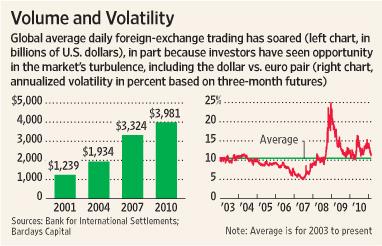

In the immediate wake of the credit crisis, I think that investors were somewhat unwilling to make concentrated bets on specific market sectors and specific assets, as part of a new framework for managing risk. To the extent that they wanted exposure to emerging markets, then, they would achieve this through buying broad-based indexes and baskets of currencies. As a result of this indiscriminate investing, prices for emerging market stocks, bonds, currencies, and other assets all rose simultaneously, which rarely happens.

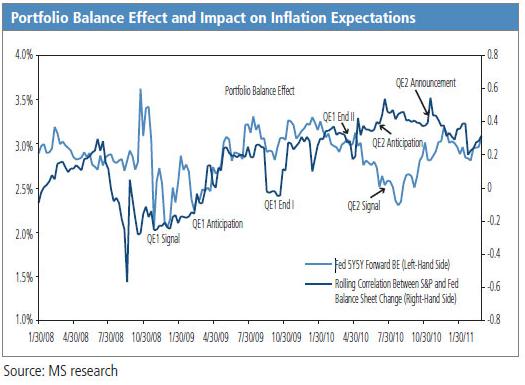

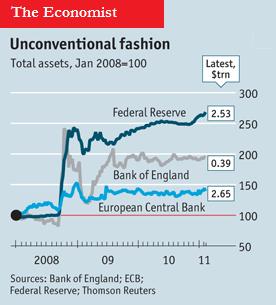

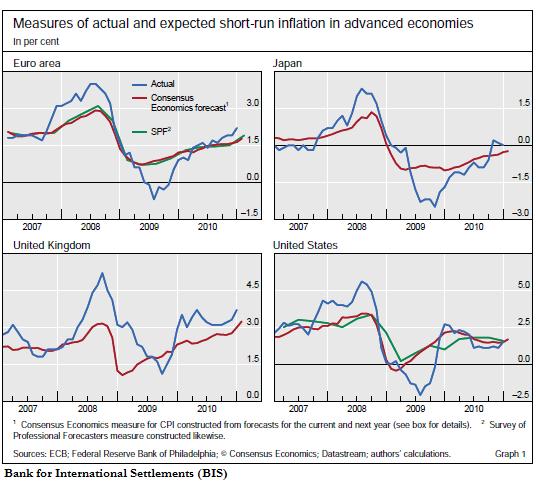

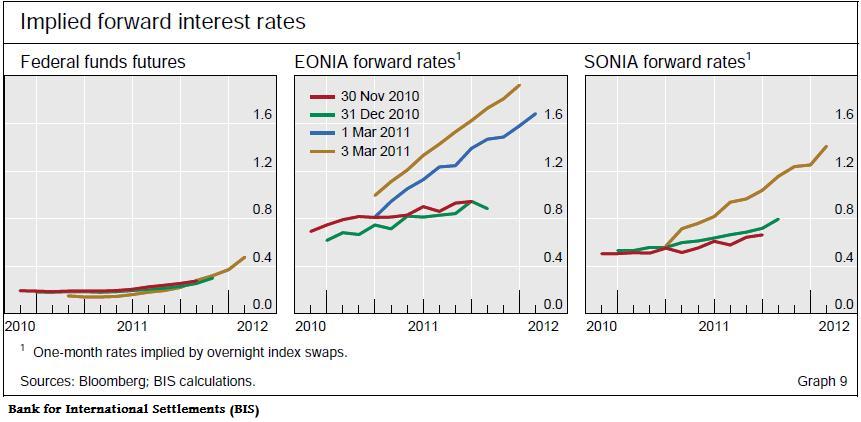

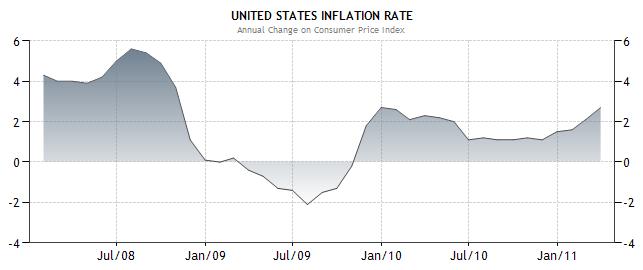

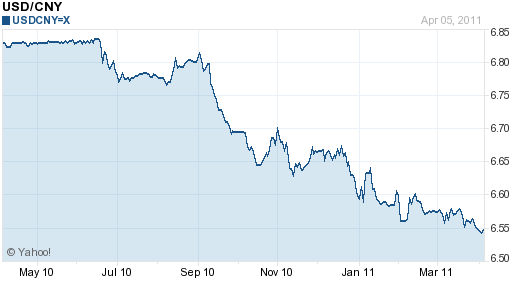

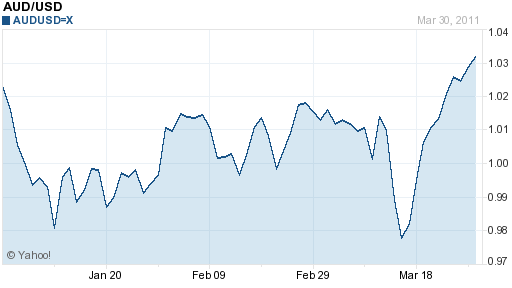

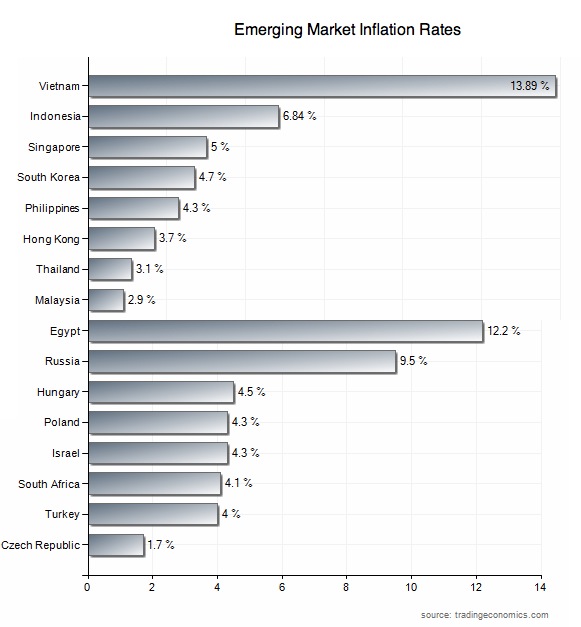

Around November of last year, that started to change. The currency wars were in full swing, inflation was rising, and there were doubts over whether EM central banks would have the stomach to tighten monetary policy, lest it increase the appreciation pressures on their respective currencies. EM stock and bond markets sputtered, and EM currencies dropped across the board. Shortly thereafter, I posted Emerging Market Currencies Still Have Room to Rise, and currencies resumed their upward march. It wasn’t until recently, however, that bond and stock prices followed suit.

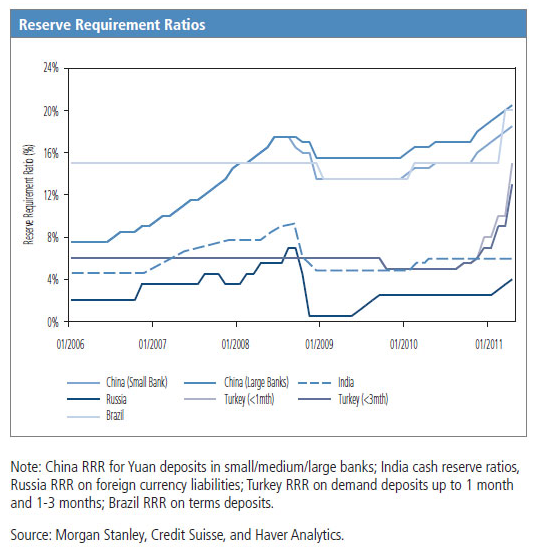

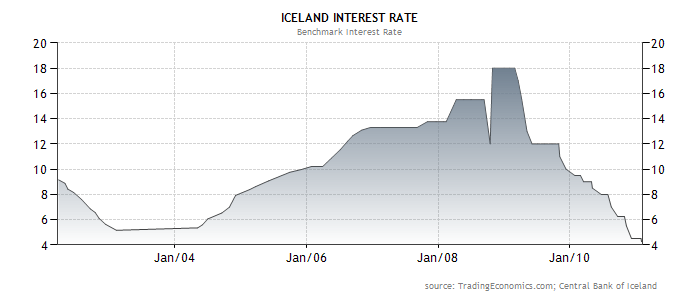

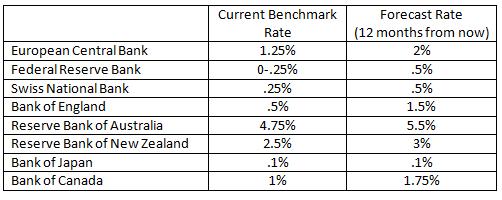

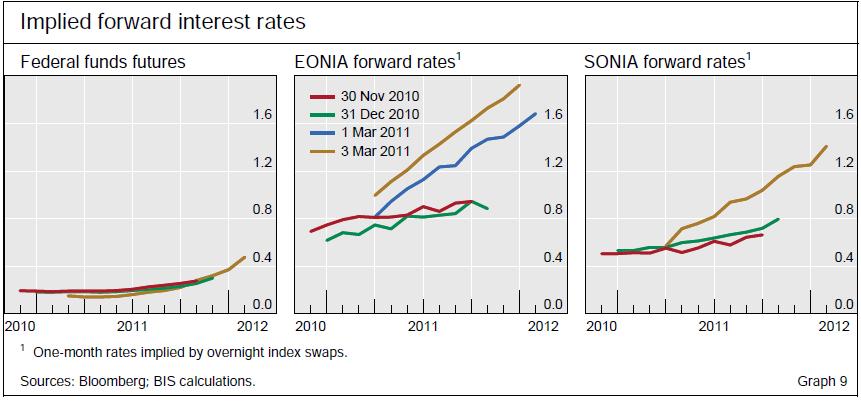

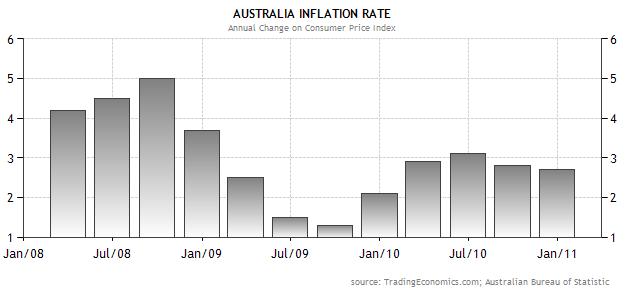

What changed? In a nutshell, emerging market central banks have gotten serious about tackling inflation. That’s not to say that they raised interest rates and accepted currency appreciation as an inevitable byproduct. On the contrary, they have adopted so-called macroprudential measures (quickly becoming one of the buzzwords of 2011!), with the goal of heading off inflation without influencing broader economic growth. Most EM central banks have sought to achieve this by raising their required reserve ratios (see chart above), limiting the amount of money that banks can lend out. In this way, they sought to curtail access to credit and limit growth in the money supply without inviting a flood of yield-seeking investors from abroad. Other central banks have gone ahead and hiked interest rates (namely Brazil), but have used taxes and other types of capital controls to discourage speculators.

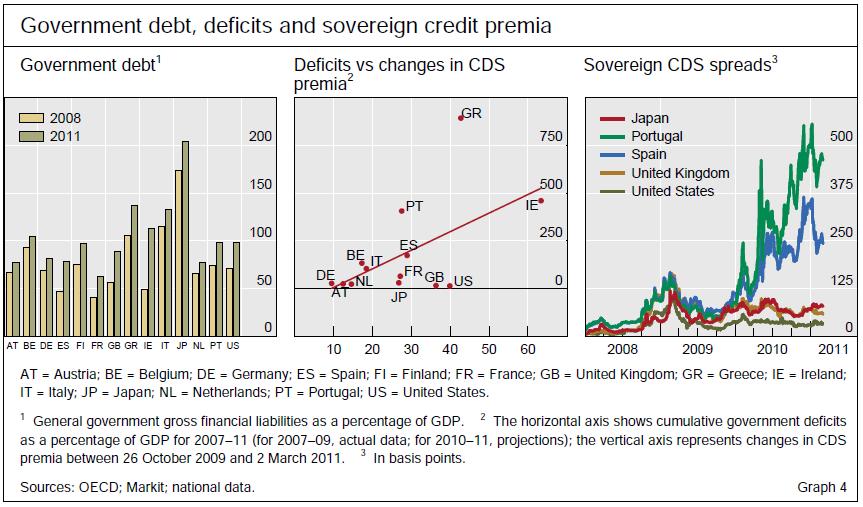

You can see from the chart of the JP Morgan Emerging Market Bond Index (EMBI+) below that EM bond markets have rallied, which is the opposite of what you would normally expect from a tightening of monetary policy. However, since EM central banks have thus far implemented tightening without directly influencing interest rates, bond yields haven’t risen as you might expect. In addition, whereas sovereign credit ratings are falling in the G7 as a result of weak fiscal and economic outlooks, ratings are actually being raised for the developing world. As a result, EM yields are falling, and the EMBI+ spread to US Treasury securities is currently under 3 percentage points.

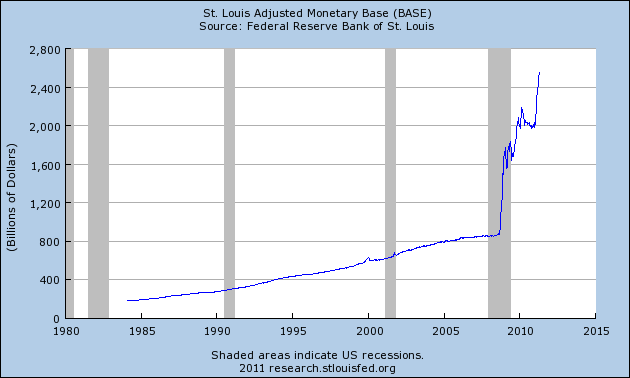

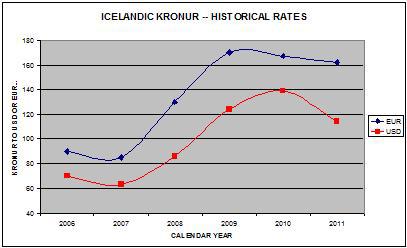

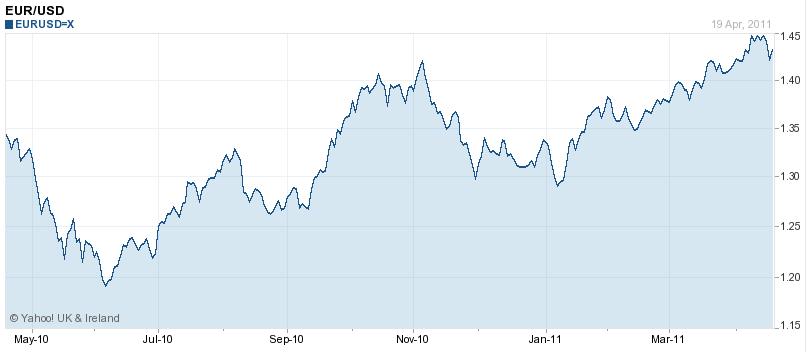

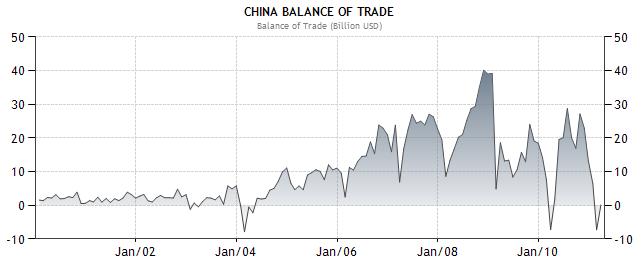

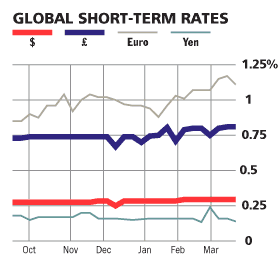

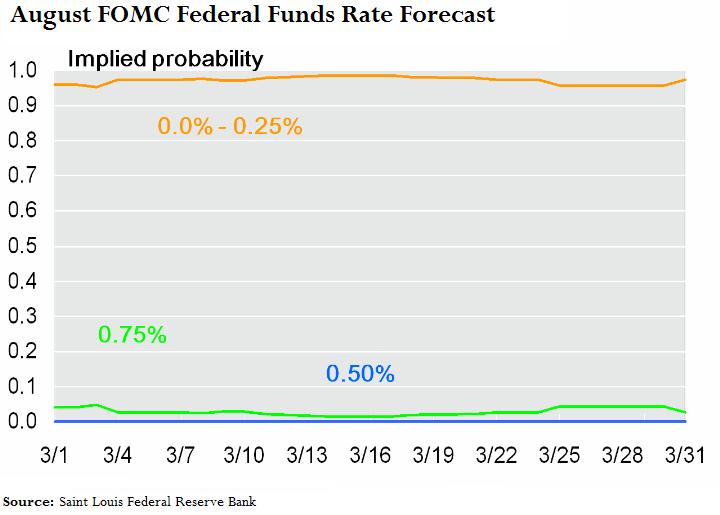

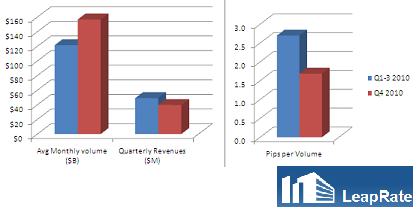

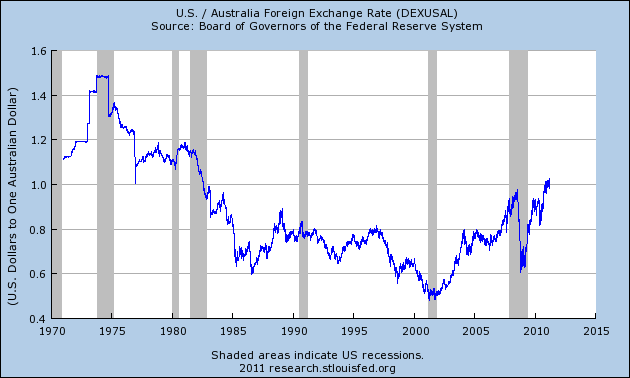

The primary impetus for buying emerging markets continues to come from interest rate differentials. Given that interest rates remain low (on both an historical and inflation-adjusted basis), however, it’s unclear whether support for EM currencies will remain in place, or is even justified. Furthermore, I wonder if demand isn’t being driven more by dollar weakness than by EM strength. If you re-cast the chart above relative to the euro, the performance of EM currencies is much less impressive, and in some cases, negative. This trend is likely to continue, as Ben Bernanke’s recent press conference confirmed that the Fed isn’t really close to hiking interest rates.

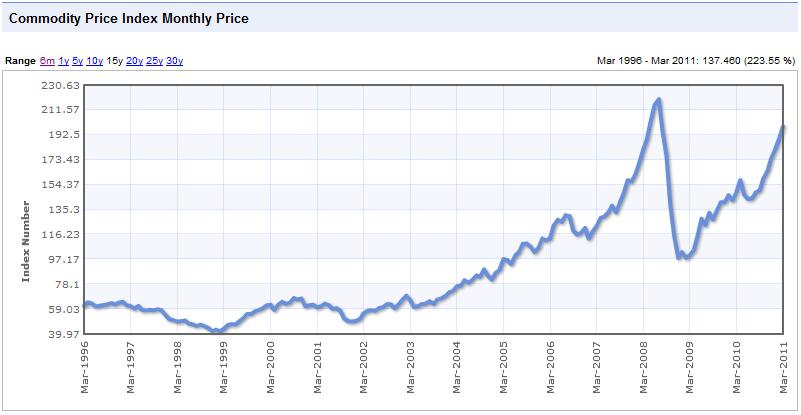

Ultimately, the outlook for EM currencies is tied closely to the outlook for inflation. If raising the required reserve ratios is enough to head off inflation (and other forces, such as rising commodity prices, abate), then EM central banks can probably avoid raising interest rates. In that case, you can probably expect a correction in forex markets, which will be amplified by rate hikes in the G7. On the other hand, if inflation continues to rise, broad EM interest rate hikes will become necessary, and the floodgates will have been opened to carry traders. Either way, the gap between the high-yielding currencies and the low-yielding ones will continue to widen. In answering the question that I posed above, I expect that regardless of what happens, investors will only become more discriminate. EM central banks are diverging in their conduct of monetary policy, and it no longer makes sense to treat all EM currencies as one homogeneous unit.

Either way, the gap between the high-yielding currencies and the low-yielding ones will continue to widen. In answering the question that I posed above, I expect that regardless of what happens, investors will only become more discriminate. EM central banks are diverging in their conduct of monetary policy, and it no longer makes sense to treat all EM currencies as one homogeneous unit.