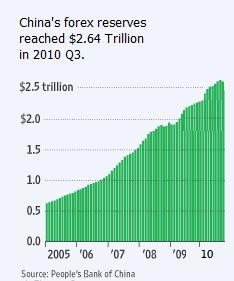

China Diversifies Forex Reserves

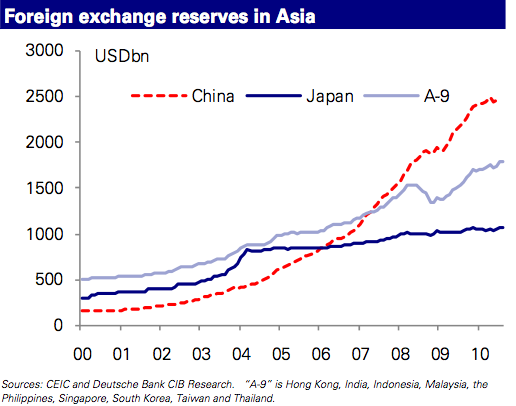

China’s foreign exchange reserves continue to surge. As of September, the total stood at $2.64 Trillion, an all-time high. However, it’s becoming abundantly clear that China is no longer content for Dollar-denominated assets to represent the cornerstone of its reserves. Instead, it has embarked on a campaign to further diversify its reserves, with important implications for the currency markets.

Despite China’s allowing the Chinese Yuan to appreciate (or perhaps because of it), hot money continues to flow in – nearly $200 Billion in the the third quarter alone. Foreign investors are taking advantage of strong investment prospects, rising interest rates, and the guarantee of a more valuable currency. In order to prevent the inflows from creating inflation and putting even more upward pressure on the RMB, the Central Bank “sterilizes” the inflows by purchasing an offsetting quantity of US Dollars and other foreign currency.

Since the Central Bank does not release precise data on the breakdown of its reserves, analysts can only guess. Estimates range from the world average of 62% to as high as 75%. At least $850 Billion (this is the official tally; due to covert buying through offshore accounts, the actual total is probably higher) of its reserves are held in US Treasury securities. It also controls a $300 Billion Investment Fund, which has made very public investments in natural resource companies around the world. The allocation of the other $1.5 Trillion is a matter of speculation.

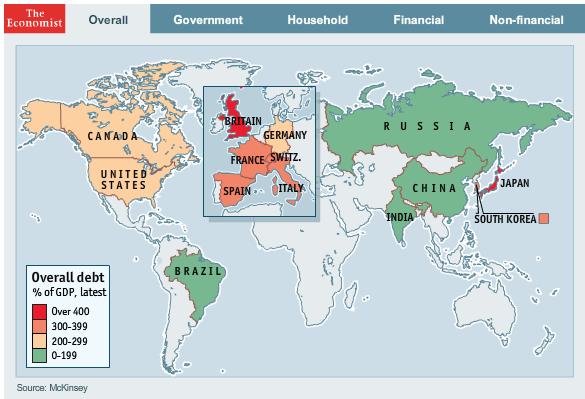

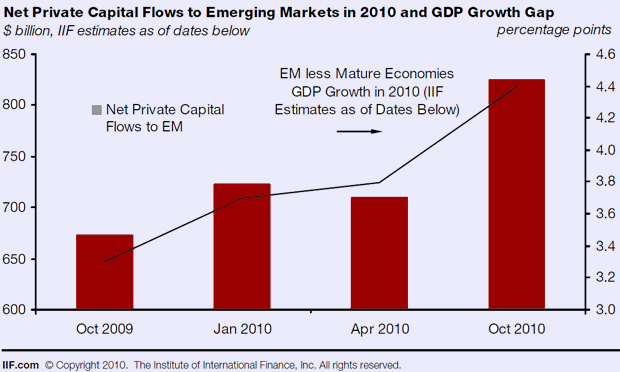

Still, China has stated transparently that it wants to diversify its reserves into emerging market currencies, following the global shift among private investors. Investment advisers praise China for its shrewdness, in this regard: “The Chinese authorities are some of the smartest in the world. If you look at the fundamentals of a lot of these emerging markets, they are considerably better than developed markets. Who wants to be holding U.S. dollars at this stage?” However, these investments serve two other very important objectives.

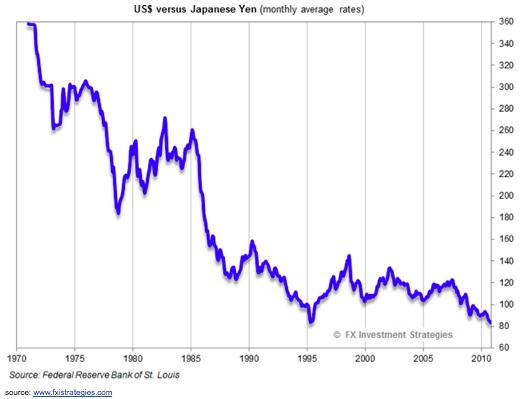

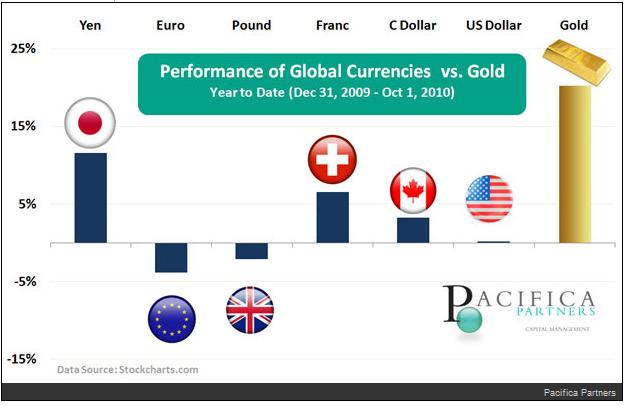

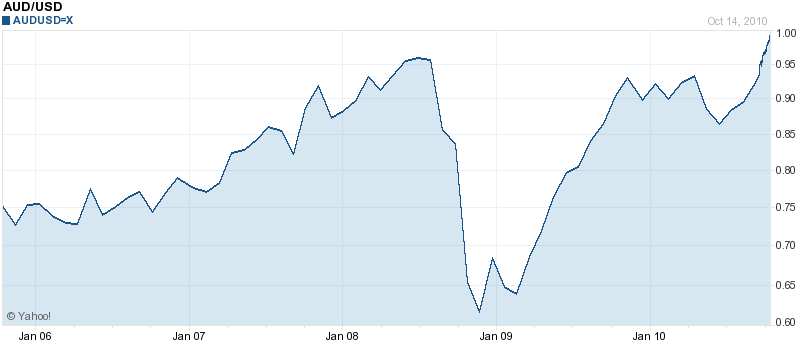

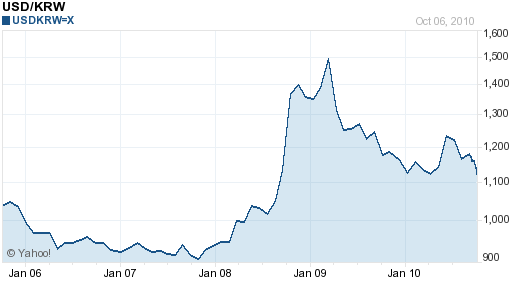

The first is diplomatic/political. When China recently signed an agreement with Turkey to conduct bilateral trade in Yuan and Lira (following similar deals with Brazil and Russia), it was interpreted as an intention snub to the US, since trade is currently conducted in US Dollars. In addition, by funding projects in other emerging markets through a combination of loans investments, China is able to curry favor with host countries, as well as to help its own economy at the same time. The second is financial: by buying the currencies of trade rivals, China is able to make sure that its own currency remains undervalued. This year, it has already purchased more than $5 Billion in South Korean bonds, and perhaps $20 Billion in Japanese sovereign debt, sending the Won and the Yen skywards in the process.

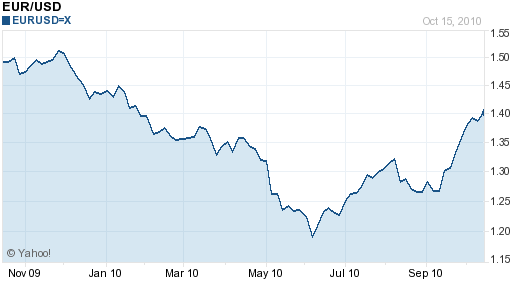

China’s purchases of Greek and (soon) Italian debt serve the same function. It is seen as an ally to financially troubled countries, while its efforts help to keep the Euro buoyant, relative to the RMB. According to Chinese Premier Wen JiaBao, “China firmly supports Greece’s efforts to tackle the sovereign debt crisis and won’t cut its holdings of European bonds.”

For now, China remains deeply dependent on the US Dollar, and is still very vulnerable to a sudden depreciation it its value. For as much as it wants to diversify, the supply of Dollars and the liquidity with which they can be traded means that it will continue to hold the bulk of its reserves in Dollar-denominated assets. In addition, the Central Bank has no choice but to continue buying Dollars for as long as the RMB remains pegged to it. At some point in the distant future, the Yuan will probably float freely, and China won’t have to bother accumulating foreign exchange reserves, but that day is still far away. For as long as the peg remains in place, the Dollar’s status as global reserve currency is safe.