July 6th 2009

Forex Reserve Growth Could Slow

Most of the recent discussion surrounding foreign exchange reserves has focused on the allocation of those reserves; specifically, whether or not these reserves will be invested in Dollar-denominated assets to the same extent as before. But what if this discussion fails to see the forest through the trees? In other words, this issue is built on the implicit premise that Central Banks will continue to build their forex reserves, and hence they need a place to invest them. With this post, I will examine whether this is indeed the case.

Since the start of the credit crisis, forex reserve growth has slowed as Central Banks (mainly in emerging markets) began to deploy some of their cash: “In the first quarter of 2009, foreign reserves were at 80% of their June 2008 levels in Korea and India, around 75% in Poland and 65% in Russia.” Most of the spending was used for direct intervention in currency markets and to finance capital outflows, as risk-averse investors moved funds out of emerging markets. Russia, alone, spent nearly $200 Billion trying to prevent a complete collapse in confidence in the Ruble.

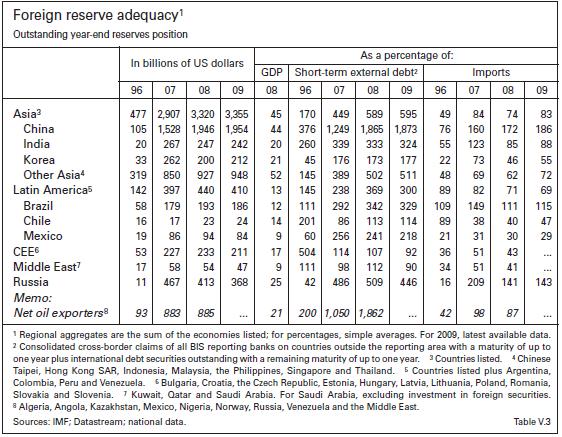

Thanks to their prudence following the 1997 Southeast Asian economic crisis, however, reserves are still more than adequate based on most measures: “A well known rule of thumb (the so-called Guidotti-Greenspan rule) is that foreign reserves should cover 100% of external debt coming due within one year. In 2008, almost all EMEs far exceeded this threshold – coverage was more than 400% in Asia and Russia and around 300% in Latin America. Another rule of thumb, that foreign reserves should cover three to six months of imports (ie 25–50% of annual imports) was also typically exceeded at the end of 2008.” Even despite the recent declines, coverage remains strong enough to meet financing requirements for the immediate future. China, whose cache of forex is by far the world’s largest, boasts a coverage ratio of nearly 2,000%!

Given such robustness, it’s clear that the impetus to continue accumulating reserves has eroded slightly. Central Banks have also come to realize how vulnerable they are to credit and currency risk, vis-a-vis the allocation of their reserves, which means that the best alternative going forward is probably to start investing in commodities and/or domestic economic initiatives. China has already begun to move in this direction.

Given such robustness, it’s clear that the impetus to continue accumulating reserves has eroded slightly. Central Banks have also come to realize how vulnerable they are to credit and currency risk, vis-a-vis the allocation of their reserves, which means that the best alternative going forward is probably to start investing in commodities and/or domestic economic initiatives. China has already begun to move in this direction.

There are several alternatives that are less risky/expensive than directly holding foreign exchange reserves. “First, in October 2008 four EME central banks each entered into a $30 billion reciprocal currency arrangement with the US Federal Reserve. Second, a $120 billion multilateral facility, drawing on international reserves, was recently established in East Asia…Third, recent G20 initiatives have called for large increases in resources for international financial institutions…[such as the] IMF’s recently created Flexible Credit Line.” Such programs provide countries in crisis with the cash to draw from without forcing them to build up reserves in advance.

To be fair, not all Central Banks are prepared to break from the current system. “In spite of significant interventions in the fourth quarter of 2008, many EMEs still had larger foreign reserves at the end of 2008 than they did in 2007.” Reports are coming in that Indian and Korean reserves, for example, have reached their highest levels since the collapse of Lehman Brothers last fall. This is sounding alarm bells for economic officials: “There is a hope the lesson taken away from the current experience is not that these countries need even larger foreign exchange reserves. These things are not terribly efficient. Our concern is that these things are going to be built up even further as a consequence.”