Jan. 5th 2011

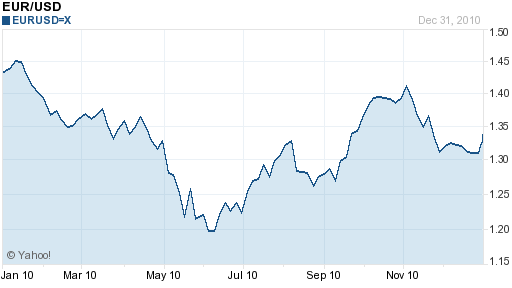

Emerging market assets/currencies registered some unbelievable gains in 2010 as the global economy emerged from recession and investor risk appetite picked up. In the last few months, however, emerging market currencies gave back some of their gains as the EU sovereign debt crisis flared up and the currency wars began to rage. Given that neither of these uncertainties is likely to be resolved anytime soon, 2011 could be a tumultuous year for emerging markets.

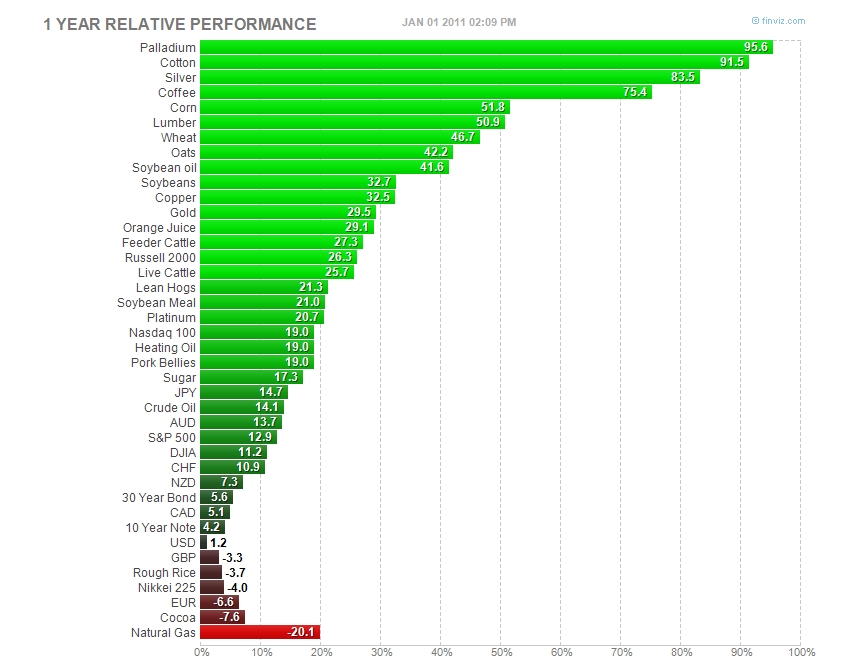

Let’s look at the numbers for emerging markets in 2010. The highlights for currencies were the Malaysian ringgit and Thai baht rose, both of which “rose around 10% against the dollar, to their strongest levels since the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s. The South African rand was up 14% versus the dollar. It was a minor currency, however, that was the world’s best-performing: Mining-rich Mongolia’s togrog finished the year 15% higher against the dollar.” After being allowed to resume its appreciation, the Chinese Yuan rose by a modest 3.5%.

The J.P. Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index Global returned a record 11.9% in 2010, to the extent that now trades at a modest 2.5% spread over US Treasury bonds. The standout was probably Argentina, whose sovereign debt returned a whopping 35% over the year. Switching to equities, the MSCI Emerging Markets Index returned 16.4%, handily beating the MSCI World Index, which itself rose by an impressive 9.6%. The individual top performing stock markets in 2010 unsurprisingly were “Frontier markets such as Sri Lanka (+96.0%), Bangladesh (+83.5%), Estonia (+72.6%), Ukraine (+70.2%), the Philippines (+56.7%) and Lithuania (+56.5%).” In total, an estimated $825 Billion in private capital flowed into emerging markets during the year, including $53 Billion into local currency bonds.

Emerging markets took advantage of the surge in investor interest to issue record amount of local currency debt and through a plethora of massive stock IPOs. Still, the intractable rise in currency and asset prices was generally seen as an undesirable trend, and emerging markets took significant steps to counter it. More than a dozen central banks have already intervened directly in currency markets in a bid to hold down their currencies. According to the IMF, “Emerging nations had accumulated $1.2 trillion in currency reserves between the financial crisis’s peak in early 2009 and the third quarter of 2010,” including ~$300 Billion in Asia ex-China. Some countries, such as Brazil – poured $1 Billion a week into forex markets during the height of their intervention campaigns.

Speaking of Brazil, it was also among the first to impose capital controls, in the form of a 6% tax on foreign bond investors. Thailand, South Korea, Taiwan and Indonesia have also imposed capital controls, while Mexico has tapped an IMF credit line, which it can use to “manage the stability of its external balances.” Moreover, these countries collectively won an important victory at the fall meeting of the G20, by receiving formal permission for all of these measures.

Alas, most of these inflows were probably justified by fundamentals, which means that they are more difficult to fight against than if they were merely the product of speculation. For example, “Developing countries expanded at a 7.1 per cent rate, compared with 2.7 per cent in advanced countries.” Moreover, emerging market stocks are trading at an average P/E multiple of 14.5, well below their recent historical average. This means that in spite of impressive performance in 2010, corporate profits are still rising faster than share prices. In addition, yields on emerging market sovereign debt still exceed the yields on comparable debt for western countries, despite being lower risk in some ways.

While most of these trends are expected to persist in 2011, there is one overriding wild card. How emerging markets respond to this issue could determine whether emerging market currencies outperform again in 2011 or whether they sink back to more normal levels. Thanks to stimulative economic and fiscal policies, easy credit, and relatively loose monetary policies, emerging markets recorded phenomenal GDP growth in 2010. The downside has been inflation.

Inflation in Brazil and China, for example, officially exceeds 5%. (The actual rates are almost certainly higher). These countries, and a handful of others, are now in the awkward position of trying to control inflation without stimulating further currency appreciation. If they raise interest rates, economic growth and price growth will almost certainly moderate. By the same token,speculative hot money will probably continue to flow in. If they don’t tighten policy, however, inflation could easily spiral out of control, provoking economic stability and even social unrest. The upside is that real interest rates will turn negative, and their currencies will probably be depreciated by investors.

Most analysts expect emerging market central banks to gradually hike interest rates over the next couple years. For fear of stoking further speculation, however, policy will probably remain somewhat accommodative and will be accompanied by strict capital controls. Meanwhile, economic growth should begin to pick up in the industrialized world, accompanied by a similar tightening of monetary and fiscal policy. As a result, investors will be forced to decide whether risk-adjusted real returns in emerging markets are adequate, and if not, whether to reverse the flow of funds back into the industrialized word.

Emerging Market Currencies in 2011

Emerging market assets/currencies registered some unbelievable gains in 2010 as the global economy emerged from recession and investor risk appetite picked up. In the last few months, however, emerging market currencies gave back some of their gains as the EU sovereign debt crisis flared up and the currency wars began to rage. Given that neither of these uncertainties is likely to be resolved in the near future, 2011 could be a tumultuous year for emerging markets.

Let’s look at the numbers for emerging markets in 2010. The highlights for currencies were the Malaysian ringgit and Thai baht rose, both of which “rose around 10% against the dollar, to their strongest levels since the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s. The South African rand was up 14% versus the dollar. It was a minor currency, however, that was the world’s best-performing: Mining-rich Mongolia’s togrog finished the year 15% higher against the dollar.” After being allowed to resume its appreciation, the Chinese Yuan rose by a modest 3.5%.

The J.P. Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index Global returned a record 11.9% in 2010, to the extent that now trades at a modest 2.5% spread over US Treasury bonds. The standout was probably Argentina, whose sovereign debt returned a whopping 35% over the year. Switching to equities, the MSCI Emerging Markets Index returned 16.4%, handily beating the MSCI World Index, which itself rose by an impressive 9.6%. The individual top performing stock markets in 2010 unsurprisingly were “Frontier markets such as Sri Lanka (+96.0%), Bangladesh (+83.5%), Estonia (+72.6%), Ukraine (+70.2%), the Philippines (+56.7%) and Lithuania (+56.5%).” In total, an estimated $825 Billion in private capital flowed into emerging markets during the year, including $53 Billion into currency bonds.

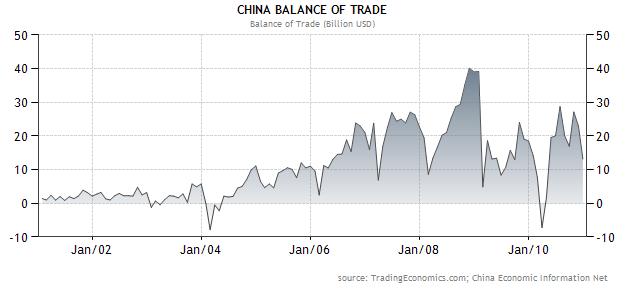

Emerging markets took advantage of the surge in investor interest to issue record amount of local currency debt and through a plethora of massive stock IPOs. Still, the intractable rise in currency and asset prices was generally seen as an undesirable trend, and emerging markets took significant steps to counter it. More than a dozen central banks have already intervened directly in currency markets in a bid to hold down their currencies. According to the IMF, “Emerging nations had accumulated $1.2 trillion in currency reserves between the financial crisis’s peak in early 2009 and the third quarter of 2010,” including ~$300 Billion in Asia ex-China. Some countries, such as Brazil – poured $1 Billion a week into forex markets during the height of their intervention campaigns.

Speaking of Brazil, it was also among the first to impose capital controls, in the form of a 6% tax on foreign bond investors. Thailand, South Korea, Taiwan and Indonesia have also imposed capital controls, while Mexico has tapped an IMF credit line, which it can use to “manage the stability of its external balances.” Moreover, these countries collectively won an important victory at the fall meeting of the G20, by receiving formal permission for all of these measures.

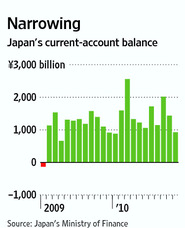

Unfortunately for emerging markets, most of these inflows were probably justified by fundamentals, which means that they are more difficult to fight against than if they were merely the product of speculation. For example, “Developing countries expanded at a 7.1 per cent rate, compared with 2.7 per cent in advanced countries.” Moreover, emerging market stocks are trading at an average P/E multiple of 14.5, well below their recent historical average. This means that in spite of impressive performance in 2010, corporate profits are still rising faster than share prices. In addition, yields on emerging market sovereign debt still exceed the yields on comparable debt for western countries, despite being lower risk in some ways.

While most of these trends are expected to persist in 2011, there is one overriding wild card. How emerging markets respond to this issue could determine whether emerging market currencies outperform again in 2011 or whether they sink back to more normal levels. Thanks stimulative economic and fiscal policies, easy credit, and relatively loose monetary policies, emerging markets recorded phenomenal GDP growth in 2010. The downside has been inflation.

Inflation in Brazil and China, for example, officially exceeds 5%. (The actual rates are almost certainly higher). These countries, and a handful of others, are now in the awkward position of trying to control inflation without stimulating further currency appreciation. In other words, if they raise interest rates, economic growth and price growth will almost certainly moderate. By the same token, speculative hot money will probably continue to flow in. If they don’t tighten policy, however, inflation could easily spiral out of control, provoking economic stability and even social unrest. The upside is that real interest rates will turn negative, and their currencies will probably be depreciated by investors.

Most analysts expect emerging market central banks to gradually hike interest rates over the next couple years. For fear of stoking further speculation, however, policy will probably remain somewhat accommodative and will be accompanied by strict capital controls. Meanwhile, economic growth should begin to pick up in the industrialized world, accompanied by a similar tightening of monetary and fiscal policy. As a result, investors will be forced to decide whether risk-adjusted real returns in emerging markets are adequate, and whether to reverse the flow of funds into emerging markets.