June 10th 2011

Emerging Market Currencies Still Look Good for the Long-Term

In my previous update on emerging market currencies, I wrote that in the short-term, it’s important not to lump them all together; high-yielding currencies must be distinguished from low-yielding ones. In this post, I’m going to backpedal a bit and argue that over the medium-term and long-term, emerging market currencies as an asset class are still a good bet.

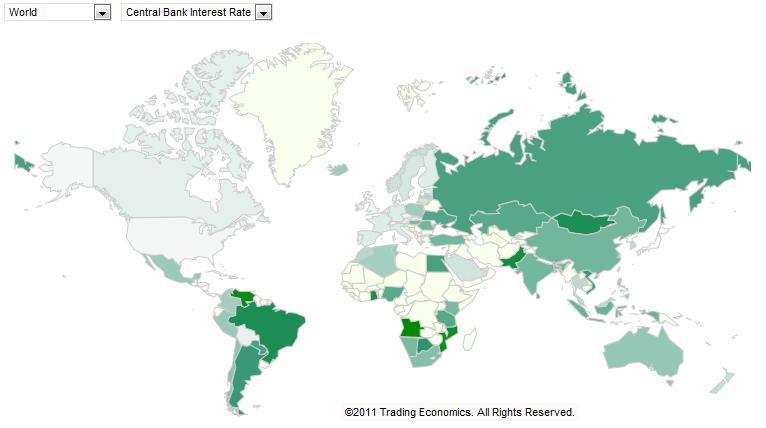

Most emerging market central banks have already begun to tighten monetary policy in order to mitigate against runaway inflation, overheating economies, and asset bubbles. You can see from the chart above (where a dark shade of green signifies a higher benchmark interest rate) that the overwhelming majority of high-yielding currencies belong to emerging market economies. (In fact, if not for Australia, it would be possible to say all high-yielding currencies).

While industrialized central banks are also expected to begin tightening, the timetable is much less certain, due to slowing growth, high unemployment, and low inflation. If current trends continue, then, interest rate differentials should only widen further between industrialized currencies and emerging currencies. Without taking risk into account, the most profitable carry trade will involve shorting the lowest-yielding currency against the highest-yielding currency(s). Alas, liquidity must also be taken in account, and the Angolan Kwanza – with an interest rate of 20% – is probably not a viable candidate. As one fund manager summarized, “[If] we feel like it’s a country where if we exit we are sort of going to shoot ourselves in the foot [due to lack of liquidity], then we won’t go in the first place.

Over the long-term, meanwhile, emerging market currencies will receive a boost from two related forces: strong fundamentals and capital inflows. With regard to the former, emerging market economies already account for the lion’s share of global GDP growth. The World Bank projects that over the next 15 years, emerging market economies will collectively expand by 4.7%, compared to 2.3% in the developed world. As a result of this strong growth, combined with fiscal prudence, debt levels across the developing world are generally falling. It marks a significant reversal that none of the current sovereign debt crises involves an emerging market country. What is more amazing is that some emerging market economies (Mexico, Russia, and Brazil) that struggled with bankruptcy less than a decade ago now have investment-grade credit ratings!

As a result, capital flows into emerging markets should continue to surge. Even though emerging market equity and bond funds have witnessed record inflows over the last few years, portfolio allocations still remain extremely low. For example, “U.S. defined-contribution pension plans only have 2.1% of their funds allocated to developing economies, which make up nearly 50% of global GDP.” Emerging market bonds, meanwhile, account for an estimated 1% of total assets under management. This trend will be further reinforced by domestic investors, which will probably opt to keep more capital in-country.

Of course, the risks are manifold. First of all, there is a risk that these capital inflows will provoke a backlash. “Emerging countries have adopted a broad range of measures to regulate inflows and stem currency rises, increasingly resorting to capital controls and so-called macro-prudential measures such as credit curbs.” Now that they have the blessing of the IMF, emerging market currencies might conceivably be more audacious in trying to limit currency appreciation. On a related note, there is also the possibility that emerging market central banks will fall behind the curve, perhaps deliberately. Lower-than-expected interest rates and hyperinflation would certainly dent the attractiveness of going long such currencies.

Finally, it is possible that in all of their excitement, investors are bidding up emerging market assets to bubble levels. The Wall Street Journal recently reported, for instance, that commodity prices and emerging market currency returns have become strongly correlated. Given that many of these countries are in fact net importers of energy and raw materials, this shows that emerging market currencies are rising more in proportion to risk appetite than to economic fundamentals. If when this risk appetite ebbs, then, this could send emerging market currencies crashing.

June 25th, 2011 at 8:25 am

For me, emerging markets are better propositions than the developed markets.